TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION

POLITICS OF FORGIVENESS

There’s renewed interest in South Africa’s ‘TRC’ as a means to finding peace after conflict – Rajika Jayatilake reports

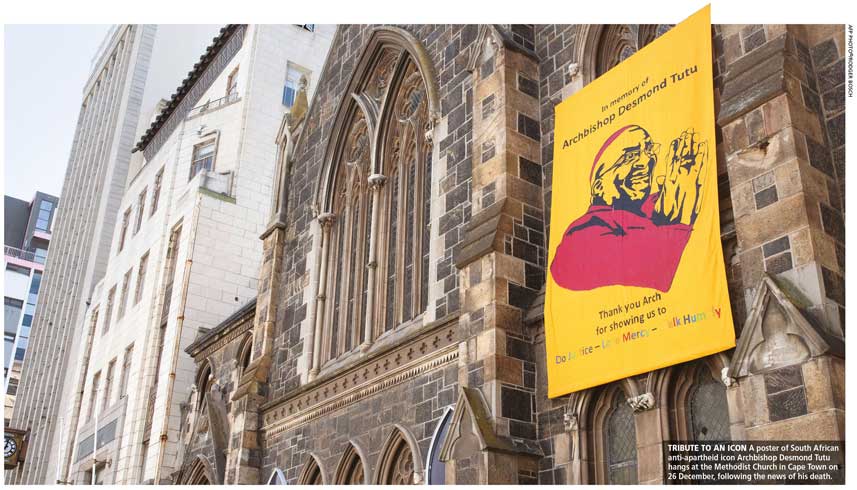

Ever since Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and South Africa’s antiapartheid icon Archbishop Desmond Tutu passed away, there has been renewed global interest in his groundbreaking accomplishments. This is especially so as regards his role in that country’s reconciliation process, which was prioritised by the government elected in 1994 in South Africa’s first democratic election with universal suffrage.

Following his election victory, the larger-than-life first black President of South Africa Nelson Mandela reached out to his county’s people and the international community, seeking to heal a nation that had been brutally wounded by apartheid crimes.

Consequently, a coalition of over 50 organisations including human rights lawyers, clergy and citizens engaged in an earnest public dialogue resulted in a piece of legislation called the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act 34 of 1995. Out of this was born South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1995. The TRC was a major departure from previous such commissions in that the focus was on gathering information on apartheid crimes between 1960 and 1994, and not prosecuting individuals for past misdemeanours.

Tutu, whom Mandela appointed to lead the TRC, insisted that justice should not be only “punitive in nature.” He believed that the TRC should “act as an incubation chamber for national healing, reconciliation and forgiveness.”

In fact, its mission was to move towards national reconciliation based on forgiveness following a complete exposure of apartheid’s horrors as gleaned from perpetrators’ confessions and victims’ traumatic experiences.

While shouldering the monumental responsibility of being the Chairman of the TRC over three years, the archbishop gifted the world many timeless pearls of wisdom.

Tutu observed: “Forgiving and being reconciled to our enemies or loved ones is not about pretending that things are other than they are. It’s not about patting one another on the back and turning a blind eye to the wrong. True reconciliation exposes the awfulness, the abuse, the hurt, the truth.”

The TRC comprised 17 commissioners (nine men and eight women) and was divided into three committees that were supported by around 300 staffers.

Those committees included the Human Rights Violations Committee tasked with investigating human rights abuses; the Amnesty Committee, which was empowered to grant exemptions if the crimes were politically instigated and perpetrators told the whole truth; and the Reparations and Rehabilitation Committee, which had the responsibility of restoring the dignity of victims and developing proposals to help with rehabilitation.

Tutu acquired firsthand knowledge of forgiveness through this process. The archbishop said: “Forgiving is not forgetting; it’s actually remembering – but not using your right to hit back. It’s a second chance for a new beginning. And the remembering part is particularly important. Especially if you don’t want to repeat what happened.”

South Africa’s TRC gave perpetrators of political crimes the opportunity to communicate truthful and complete accounts of their actions, and ask for forgiveness if they wanted to. On the flip side, the victims of political crimes were given a chance to voice the pain and suffering they had carried within themselves for years.

In fact, the TRC recorded the testimony of 21,000 victims while 2,000 of them appeared at public hearings. The commission also received 7,112 applications for amnesty. However, with the bar raised for discourse and amnesty standards, only 849 applicants were granted exemption from punishment.

Moreover, South Africa’s TRC had four goals: firstly, to promote national unity and reconciliation based on a firm understanding of the past; secondly, to grant amnesty to perpetrators who were completely truthful publicly; thirdly, to bring closure to families of the missing and restore the dignity of victims; and fourthly, to record the successes and failures of the first three goals, and show the way forward.

This apart, the people of South Africa willingly followed the archbishop’s path of forgiveness – not merely because he preached it but also as a result of the fact that his own life reflected such a godly quality. Besides, it would have been impossible to switch peacefully from apartheid and conflict to democracy without genuine forgiveness.

This alone makes Desmond Tutu an outstanding peacemaker who had clarity of vision and resoluteness of purpose. “True peace must be anchored in justice and an unwavering commitment to universal rights for all humans – regardless of ethnicity, religion, gender, national origin or any other identity attribute,” the Christian prelate said.

However, though South Africa’s model of a ‘truth and reconciliation commission’ can be considered a contemporary miracle, it can’t be easily transposed to other societies in the same way.

The archbishop was quite clear on this when he asserted that “there is no handy road map for reconciliation. As our experience in South Africa has taught us, each society must discover its own route to reconciliation. Reconciliation cannot be imposed from outside – nor can someone else’s map get us to our destination. It must be our own solution.”

As our experience in South Africa has taught us, each society must discover its own route to reconciliation

Leave a comment