COVER STORY

EXCLUSIVE

DEVELOPMENT BAROMETER

Priorities for a nation in transition

An in-depth assessment of Sri Lanka’s development prospects

BY Dr. Idah Pswarayi-Riddihough

Sri Lanka’s poverty reduction programme, fiscal consolidation, economic growth drivers, ease of doing business and right to information are among the hot button subjects that form the nucleus of the nation’s transition to a viable hub for the South Asian region.

Sri Lanka’s poverty reduction programme, fiscal consolidation, economic growth drivers, ease of doing business and right to information are among the hot button subjects that form the nucleus of the nation’s transition to a viable hub for the South Asian region.

In this exclusive interview with LMD, the World Bank’s Country Director for Sri Lanka and the Maldives in the South Asia region outlines the key priorities for Sri Lanka to leverage on in its quest for accelerated economic growth and all-round prosperity.

A Zimbabwean national, Dr. Idah Pswarayi-Riddihough joined the World Bank in 1995 as a Young Professional, having earned her PhD from Oxford University in 1993. Since then, she has held several operational and corporate management positions of which the most recent was Director of Strategy and Operations in the Human Resources Vice Presidency.

Pswarayi-Riddihough has worked in four regions: South Asia, East Asia, Middle East and North Africa, as well as Africa. In South Asia, her last posting was as the Director of Operational Services from 2012 to 2014 when she supervised the teams that covered operations in financial management and procurement.

Pointing to the broader role of development agencies such as the World Bank in assisting nations to fulfil their growth objectives and ensure that citizen’s rights are preserved, Pswarayi-Riddihough observes: “When citizens feel they are being asked to contribute to the country’s development goals, and at the same time the government opens up and shares information on how it is performing, it enhances cohesiveness and support for tough but much needed decisions.”

– LMD

Q: How would you describe the level of poverty in Sri Lanka and progress on this front in the last two or three decades?

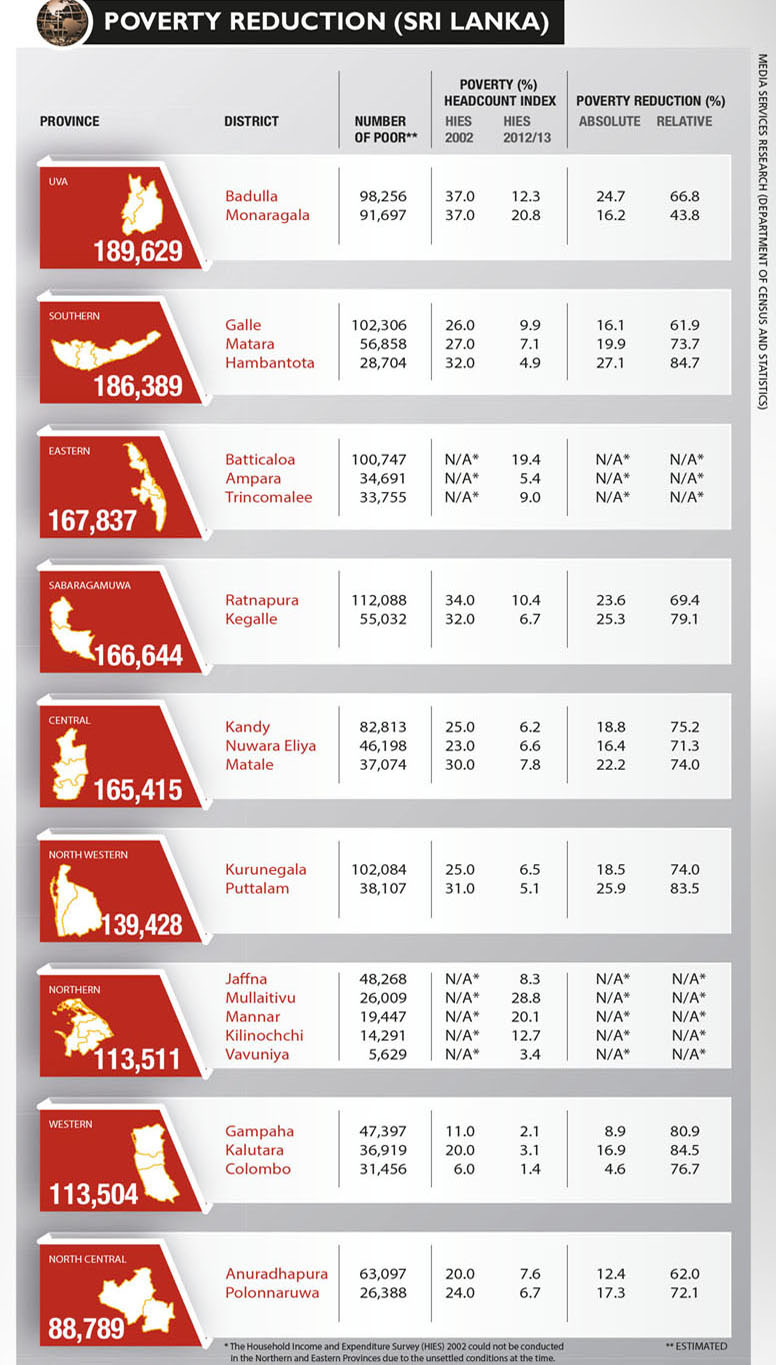

A: Extreme poverty is now rare in the country except for a few pockets in some districts. Nevertheless, moderate poverty remains widespread.

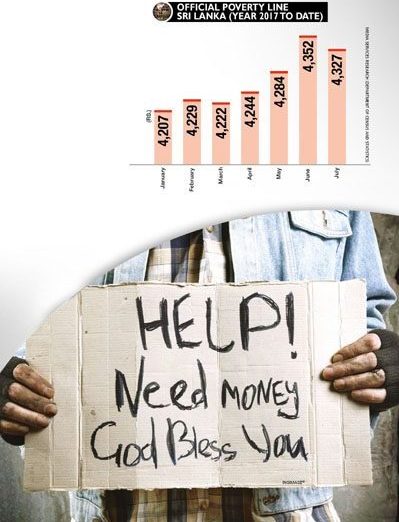

The international definition of ‘extreme poverty’ is the share of the population living on less than US$ 1.90 a day in adjusted US Dollars. By this standard, less than two percent of Sri Lankans were poor in 2012/13 – the most recent year for which household survey data is available. The official national poverty rate – at 6.7 percent in 2012/13 – is only slightly higher.

Regardless of how poverty is measured, Sri Lanka has taken rapid strides in the last 15 years in reducing it. Similarly, the share of the population living on less than five dollars a day fell from 76 percent to 44 percent during this period.

Progress has been particularly notable in the estate sector where poverty fell from 30 percent in 2002 to 11 percent in 2012/13. This improvement in living standards is visible in myriad indicators from increased incomes to higher ownership rates of key assets as well as increased school attendance and improved access to electricity.

Progress has been particularly notable in the estate sector where poverty fell from 30 percent in 2002 to 11 percent in 2012/13. This improvement in living standards is visible in myriad indicators from increased incomes to higher ownership rates of key assets as well as increased school attendance and improved access to electricity.

While more recent information on poverty is not available, the labour market continued to perform well in 2014 and 2015 as non-farm employment grew and unemployment ticked downward. New data on poverty has been collected for last year and is expected to become available in late 2017.

These favourable statistics are of cold comfort to millions of Sri Lankans who continue to struggle to find food and meet basic needs.

Official poverty statistics are based on a minimum nutritional benchmark that was established in 2002. Establishing a new benchmark in line with current consumption patterns could classify many more people as poor because a large proportion of Sri Lankans live only slightly above the official poverty threshold and are vulnerable to falling back into deprivation.

In 2013 for example, 45 percent of Sri Lankans lived on less than five dollars a day – or Rs. 235 a day in purchasing power parity terms. Moreover, there are some District Secretariat (DS) divisions – largely in Batticaloa and Mullaitivu – where the official national poverty rate ranges from 30 to 45 percent.

What lies behind these favourable trends in poverty reduction? Sri Lanka has been able to drive down poverty because the poor have earned more. And four main factors have helped.

What lies behind these favourable trends in poverty reduction? Sri Lanka has been able to drive down poverty because the poor have earned more. And four main factors have helped.

Firstly, the economy has been gradually shifting away from agriculture – where small-scale farmers often struggle to eke out a living – into industries and services.

The share of workers in agriculture has fallen from 36 percent in 2000 to 29 percent in 2015 while the share of value added to the economy from agriculture fell from 20 to 8.2 percent during the same time period.

Secondly, slow but steady industrialisation of the economy is accompanied by the expansion of urban hubs and road networks that connect regions better especially along the Colombo-Kandy-Galle/Matara corridors.

The urbanisation of the island is most visible when looking at nighttime satellite pictures that indicate a large expansion in lights shining in the Colombo-Galle-Kandy corridor.

The end of the conflict in 2009 also played an important role in reducing poverty. It led to a surge in the construction and services sectors, as well as increasing the inflow of tourists.

Meanwhile, sharp rises in international prices of food and tea spurred a major increase in minimum wages among agricultural workers. But with the recent fall in international food and tea prices, and a fading of the post-conflict boom, these sources of growth with the exception of tourism cannot be counted on to continue in the medium term.

Q: What key factors undermine Sri Lanka’s poverty reduction programme? And what are the main challenges the country is facing in this regard?

A: The government faces many obstacles to further reduce poverty, many of which are interrelated. Sri Lanka should focus on investing in its people, places, practices, programmes and policies to overcome the challenges of reducing poverty.

In terms of people, in our experience we have found that what works are policies that boost poor workers’ productivity and provide more effective support to poor households.

Boosting productivity calls for making the right investments in people: quality education and training can help workers compete in a more industrialised and internationally integrated economy.

Although educational attainment has improved over the past decade, quality remains a concern. Both Sri Lankan students and workers tend to fall behind other countries comparatively in cognitive skills assessments, while the island faces a shortage of workers with adequate technical and vocational skills.

Although educational attainment has improved over the past decade, quality remains a concern. Both Sri Lankan students and workers tend to fall behind other countries comparatively in cognitive skills assessments, while the island faces a shortage of workers with adequate technical and vocational skills.

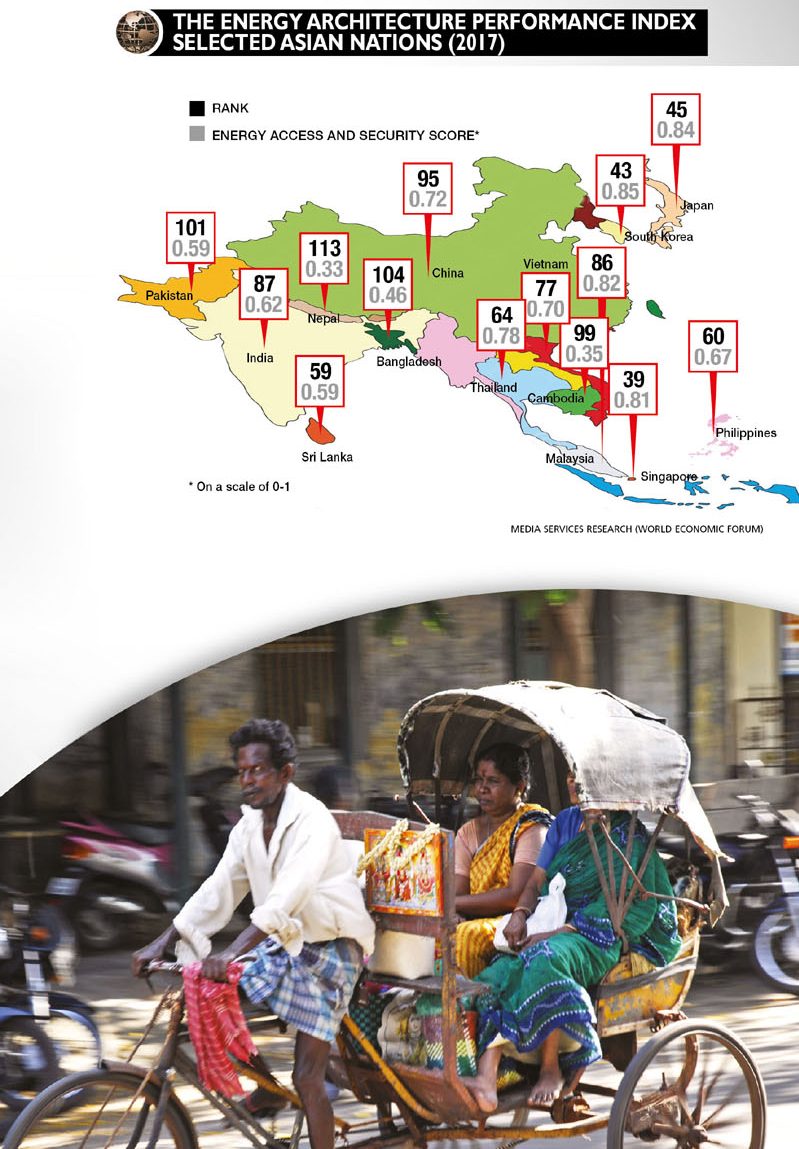

Investing in infrastructure like roads and energy in poor areas would also help make workers more productive. Many of the poor earn livelihoods in agriculture, making reforms in that sector critical for poverty reduction. Helpful reforms include modernising the sector, diversifying into higher value crops and developing the production chain to link small farmers to new markets.

Boosting exports more generally is a key challenge for Sri Lanka’s economy. Recent growth has been largely fuelled by domestic consumption and non-tradable sectors while there’s been a steady decline in commodity exports. And tax exemptions and trade preferences are common. Meanwhile, foreign direct investment (FDI) is low and specific incentives to promote it are often ineffective when compared with the commitments to maintain stable regulations and policies, and eliminate unnecessary barriers.

While export led growth is not necessarily the only path to development, it has become a strong force for poverty reduction in many countries. Improving the public service with efficient institutions that create jobs and work towards an improved quality of living is both a challenge and an opportunity to building public trust.

A well-targeted and functioning social safety net is critical for several reasons: it can help poor households invest in children in the face of further reductions in the fiscal deficit, and in natural disasters like the recent drought and flooding. So reforming safety net programmes such as Samurdhi will help identify the poor more accurately and transparently, and minimise leakage to wealthier households.

Although the method to determine beneficiaries is in great need of being updated, it’s also important to take the time to do it right by testing different methods to see what works well.

Fiscal policies can also work better for the poorest as they will expand the tax base, increasing the role of income tax, and removing tax exemptions and programmes that largely benefit wealthier households.

The government has taken welcome steps to put its fiscal house in order as the deficit fell from 7.6 percent in 2015 to 5.4 percent last year. In terms of expenditure, recent moves to phase out fertiliser subsidies and increase benefits for Samurdhi households have helped the poor. But tax collection remains a major challenge.

The government has taken welcome steps to put its fiscal house in order as the deficit fell from 7.6 percent in 2015 to 5.4 percent last year. In terms of expenditure, recent moves to phase out fertiliser subsidies and increase benefits for Samurdhi households have helped the poor. But tax collection remains a major challenge.

Q: How would you assess the distribution of wealth in Sri Lanka and beyond? Has the lack of a more equitable system led to the rise of populism across the world?

A: It’s difficult to assess the distribution of wealth as measured by asset ownership in Sri Lanka. Currently, we do not have access to information on the distribution of wealth and income from tax returns.

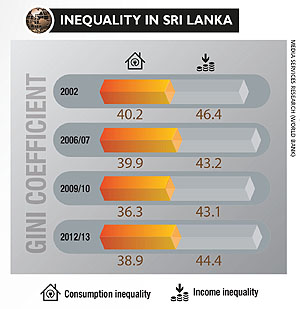

Survey data on inequality is generally considered to be less reliable than data on poverty but official data indicates a marked increase in both income and consumption inequality. Both rose substantially from 2009 to 2012/13.

During that time, the poorest 40 percent of the population captured only 15 percent of the country’s total consumption growth. Sri Lanka stands out as the only nation in the region where inequality rose substantially between 2009/10 and 2012/13.

Q: And how are development agencies like the World Bank assisting nations such as ours come out of the poverty trap?

Q: And how are development agencies like the World Bank assisting nations such as ours come out of the poverty trap?

A: Although poverty is decreasing, there is more work to be done to raise living standards. The World Bank mostly helps by providing governments with financing and technical assistance where needed.

The bank supports civil society and other grassroots development agencies through its own resources, or by leveraging trust funds from other development agencies such as the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), European Union (EU) and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

It can also leverage on its global experience and reach, to bring lessons learned from other countries to Sri Lanka through policy and project loans, and by providing technical assistance. In Sri Lanka specifically, the World Bank Group (WBG) seeks to support it in its transition to an Upper Middle-Income Country.

WBG’s Country Partnership Framework (CPF) for 2017-2020 provides the current strategic thrust of the bank’s support for macro fiscal stability and competitiveness, as well as promoting inclusion and opportunities for all, seizing green growth opportunities, improving environmental management, and enhancing adaptation and mitigation potential.

The current active World Bank portfolio in Sri Lanka comprises 17 projects with a total net commitment value of over US$ 2 billion. The education and health sectors account for 27 percent of the overall portfolio, followed by urban and rural development (23%), water (15%), and resilience to climate and disaster risk (7%).

Indeed, the World Bank has been active in the health and education sectors for over two decades. Support for the education sector includes a new higher education project operation (the Accelerating Higher Education Expansion and Development project) for 100 million dollars and an Early Childhood Development programme for US$ 50 million. Investment in early childhood development consistently brings high cumulative returns in human capital and is one of the most cost-effective ways of establishing social equity. It could help disadvantaged households and communities break the vicious cycle of poverty that’s often transmitted across generations.

A programme in the national health sector is also being supported under the Second Health Sector Development Project, which is valued at 200 million dollars. It is designed to improve the standards of the performance of the public health system, and enable it to respond better to the challenges of malnutrition and non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

The country’s economic growth has been primarily driven by the Colombo Metropolitan Region (CMR), which currently generates 45 percent of the nation’s GDP and is home to 28 percent of its population.

Recognising the importance of this region to economic growth, the World Bank is supporting Sri Lanka implement its urbanisation and rural-urban integration agenda through the Metro Colombo Urban Development Project (US$ 213 million) to assist the CMR to upgrade basic urban infrastructure, as well as implement an innovative integrated approach to urban flood control and wetland management. The Strategic Cities Development Project (US$ 202 million) is expanding the approach to urban infrastructure upgrading in Kandy, Galle and Jaffna – three strategic city regions – as well as supporting investments in urban water supply, sewage and drainage systems, cultural heritage rehabilitation, urban transport and traffic management.

Recognising the importance of this region to economic growth, the World Bank is supporting Sri Lanka implement its urbanisation and rural-urban integration agenda through the Metro Colombo Urban Development Project (US$ 213 million) to assist the CMR to upgrade basic urban infrastructure, as well as implement an innovative integrated approach to urban flood control and wetland management. The Strategic Cities Development Project (US$ 202 million) is expanding the approach to urban infrastructure upgrading in Kandy, Galle and Jaffna – three strategic city regions – as well as supporting investments in urban water supply, sewage and drainage systems, cultural heritage rehabilitation, urban transport and traffic management.

About 29 percent of the population remains engaged in agriculture and it has been an important driver of poverty reduction, accounting for about a third of the overall decline in poverty over the past decade. Sri Lanka has become self-sufficient in rice production but allowed the agriculture production structure to remain concentrated in relatively lower-valued crops.

Therefore, a new Agriculture Sector Modernization Project (US$ 125 million) seeks to assist the government to strengthen the country’s research and development, and extension system and policy related to national agriculture; improve productivity and climate resilience in irrigated agriculture; and pilot value chain models to promote diversification, and increase competitiveness and rural incomes.

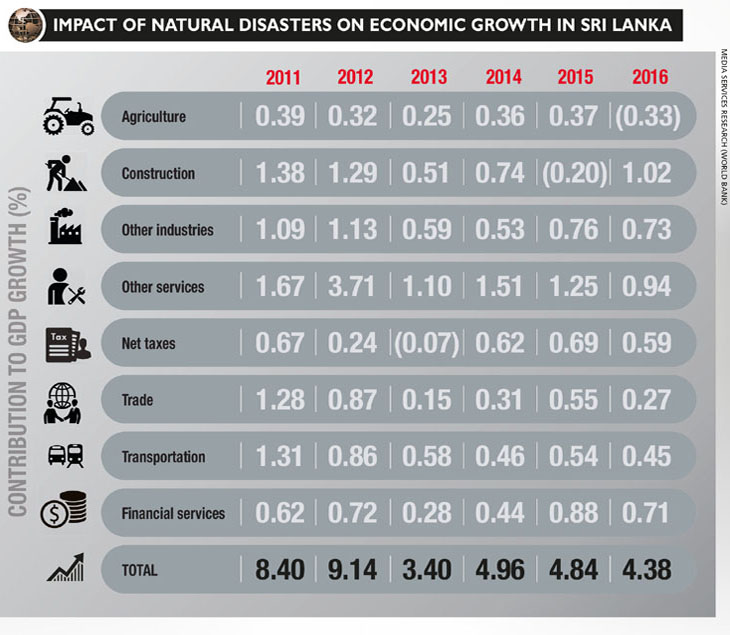

The fiscal and physical impact of natural disasters – flooding and drought in particular – has been sizeable over the past decade, and has had a disproportionate impact on the poor. Floods have cumulatively affected over 10 million people since 2000 (over 375,000 people annually on average) while droughts have affected more than five million. To increase resilience, physical investments are being financed to address short-term infrastructure weaknesses along with a contingent credit line to safeguard against immediate fiscal impacts of a disaster through the Climate Resilience Improvement Project (152 million dollars).

The fiscal and physical impact of natural disasters – flooding and drought in particular – has been sizeable over the past decade, and has had a disproportionate impact on the poor. Floods have cumulatively affected over 10 million people since 2000 (over 375,000 people annually on average) while droughts have affected more than five million. To increase resilience, physical investments are being financed to address short-term infrastructure weaknesses along with a contingent credit line to safeguard against immediate fiscal impacts of a disaster through the Climate Resilience Improvement Project (152 million dollars).

A follow-up comprehensive Disaster Risk Mitigation Project is also being prepared. And as part of its analytical and advisory activities, WBG has been helping Sri Lanka mainstream disaster risk management with a view to strengthening its early warning system.

WBG has been supporting efforts to increase access to finance for SMEs and the poor.

The World Bank carried out a development Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) at the request of the government, offering recommendations to address identified constraints.

Based on the recommendations of the FSAP, the bank recently approved a US$ 75 million project to contribute to increasing financial market efficiency and the use of financial services among micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and individuals.

Q: Last year, the World Bank referred to South Asia as the most rapidly growing region on Earth. Does this still hold true today and for the foreseeable future?

Q: Last year, the World Bank referred to South Asia as the most rapidly growing region on Earth. Does this still hold true today and for the foreseeable future?

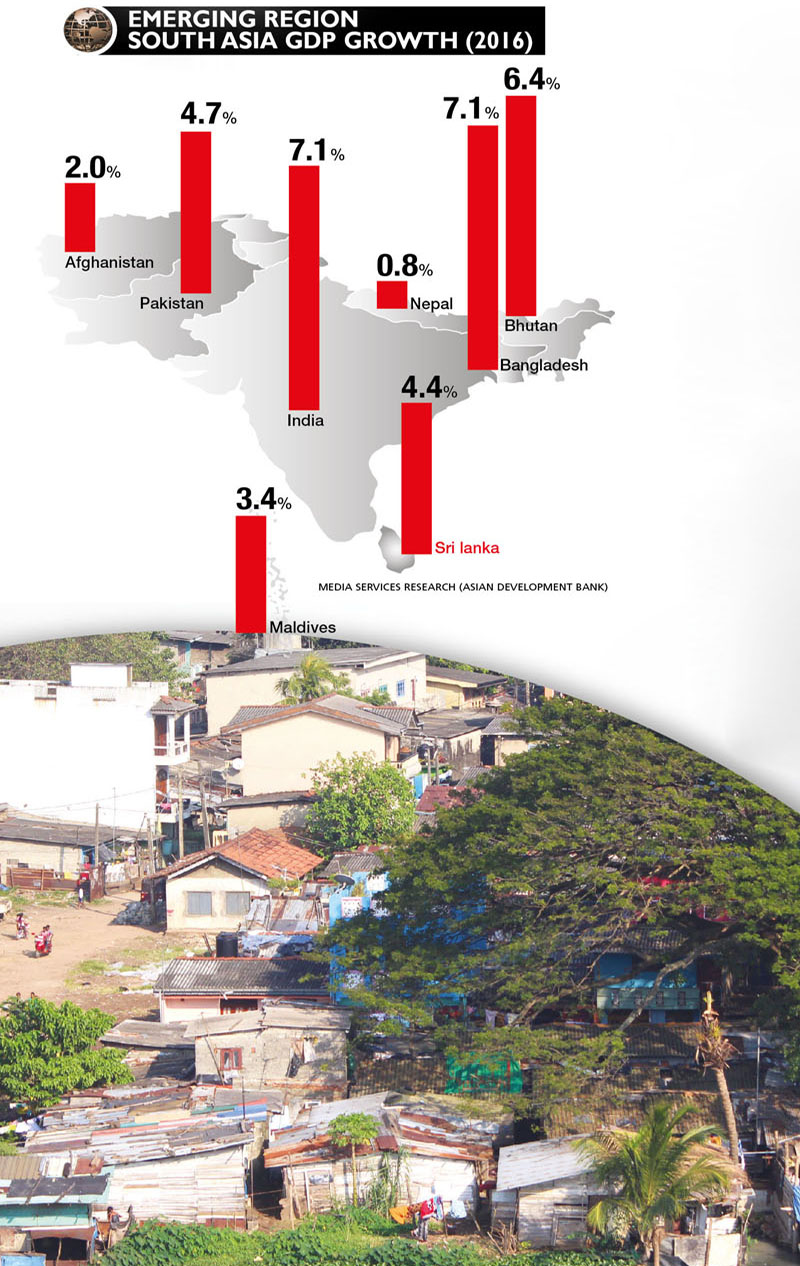

A: Yes, this holds true. In fact, South Asia has consolidated its position as the global leader in economic growth. The strong economic performance was despite the temporary setback caused by India’s demonetisation effort at the end of 2016. Growth in South Asia was higher than in East Asia where it stood at 6.3 percent while other regions are growing either much more gradually or even contracting.

Despite sub-regional differences, most South Asian countries have displayed improvements. At around seven percent, growth has been particularly high in Bhutan, Bangladesh and India.

The Indian economy benefitted from a favourable monsoon and strong urban consumption. The setback due to demonetisation was noticeable but modest. In Bangladesh, growth has been driven mainly by private investment and exports with industrial production recently reaching a record high.

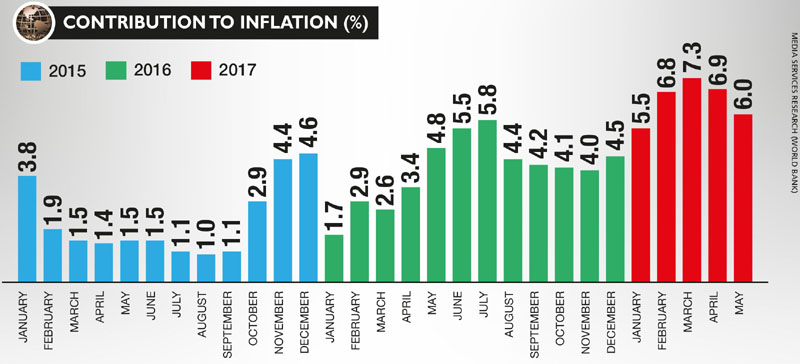

Following two consecutive years of weak growth due to devastating earthquakes and disruption in trade with India, growth in Nepal is bouncing back strongly. In Pakistan, growth has been around five percent, implying a continuation of an upward trend while in Sri Lanka, growth declined from 4.8 percent to 4.4 percent mainly due to floods and drought.

As a consequence of large investment projects, growth in the Maldives rebounded to 4.1 percent despite a slowdown in tourism. The weakest performance was in Afghanistan where security concerns have kept economic growth below population growth for yet another year. Growth could be even stronger if trade and investment were contributing to a greater extent. As in the rest of the world, trade and investment growth in South Asia disappointed in 2016. For some countries in the region, export growth was mostly negative throughout the year.

But the trend has reversed lately and the most recent data is encouraging. In Sri Lanka, exports grew strongly at the end of last year while in India, export growth accelerated to a high after six and a half years in March.

Investment rates have also been high with South Asia being second only to East Asia. But as a share of GDP, investment has been on a declining trend since 2011. And while this decline is unambiguous in India and Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan are witnessing an upward trend.

Q: How can and must we leverage on growth in the region?

Q: How can and must we leverage on growth in the region?

A: South Asia remains one of the least integrated regions in the whole world with low intra-regional trade and investment. High growth and structural reforms in India, Bangladesh and other countries offer the region opportunities to integrate more and share economic prospects.

Sri Lanka can use preferential trade agreements (PTAs) as an instrument of its trade policy and pursue them strategically to maximise benefits to itself. While the country is committed to multilateralism and needs to remain engaged in the World Trade Organization (WTO) to safeguard its interests, Sri Lanka cannot ignore the fact that nearly 50 percent of global trade now takes place through regional, ‘plurilateral’ and bilateral trade agreements.

And given that the island will have to increasingly depend on the growing markets of Asia for export growth, PTAs with China and India need to be viewed as opportunities rather than threats while carefully evaluating the costs and benefits to Sri Lanka from each PTA.

In negotiating new PTAs, Sri Lanka also needs to be mindful of the lessons from existing trade agreements – non-tariff barriers are as important to address as tariff barriers, mutual recognition agreements are critical for trade facilitation, widespread awareness campaigns are vital for information dissemination and an effective communication strategy is essential to dispel concerns regarding PTAs.

Q: The World Bank has stated that economic reforms, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme and the resumption of the EU’s GSP+ concessions “will help Sri Lanka’s economy accelerate to 5.1 percent by 2019.” What (if any) sensitivities are there to this projection?

A: The country is vulnerable to both domestic and external risks. External risks include disappointing growth performance in key nations and regions such as the US, the EU, China and the Gulf states that provide the all-important foreign exchange inflows to Sri Lanka through exports, tourism, remittances, FDIs, and private portfolio and official financing.

Quicker (than expected) rises in commodity prices would increase pressure on the balance of payments, and make domestic fuel and electricity price reforms more difficult to pursue.

On the fiscal side, risks include the delay in implementing structural revenue measures and slower (than expected) improvement in tax administration. Tightening global financial conditions would increase the cost of debt and make rolling over the maturing Eurobonds from 2019 more difficult.

Finally, the increasing occurrence and impact of natural disasters could have an adverse impact on growth, the fiscal consolidation path, the trade balance and poverty reduction.

Q: What are the longer-term structural development challenges facing Sri Lanka as it strives to make progress from its present status of a middle-income nation?

Q: What are the longer-term structural development challenges facing Sri Lanka as it strives to make progress from its present status of a middle-income nation?

A: In our Systematic Country Diagnostic (SCD) last year, we identified the following structural challenges: the fiscal challenge, promoting more and better jobs for the bottom 40 percent, social inclusion and sustainability (environmental, external account and demographic), crosscutting governance, and gender and development challenges.

These challenges increasingly put at risk future economic growth and stability, and so must be addressed through determined reforms. They are interlinked, and require a comprehensive and coordinated approach. Therefore, adopting a piecemeal solution to address them is unlikely to be successful.

Although a turbulent external environment, domestic political considerations and institutional constraints on policy implementation make it challenging, strong political will and support of the bureaucracy could help advance the reform agenda. And steps must be taken to ensure the support of the private sector, civil society and other stakeholders, by means of improved communications on the costs and benefits of the reform agenda.

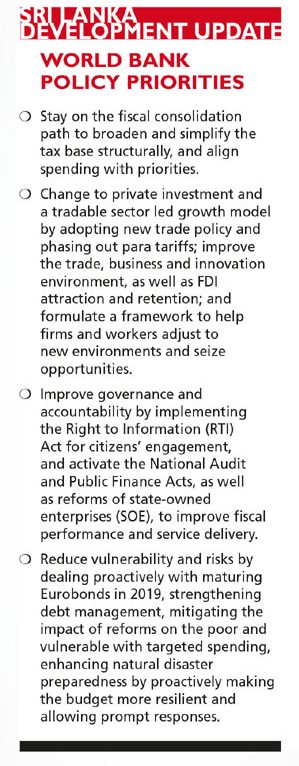

In the near to medium term, this translates into the four sets of policy priorities that are outlined in our Sri Lanka Development Update.

Q: The World Bank has cited key challenges such as boosting investment, and realigning public spending and policy with the needs of a middle-income country. Could you elaborate on this?

A: Sri Lanka must shift from a public investment, non-tradable sector driven growth model, to one comprising private investment, a tradable sector led model to sustain its growth. It must also strengthen its structurally weak current account, create new and productive jobs in the private sector, as well as reduce poverty.

While Sri Lanka has grown rapidly in the past, the non-tradable drivers of such growth are unlikely to be adequate for inclusive and sustainable growth in the coming decade.

While Sri Lanka has grown rapidly in the past, the non-tradable drivers of such growth are unlikely to be adequate for inclusive and sustainable growth in the coming decade.

Given the context of continued weak external liquidity, foreign exchange generated through tradable sectors is even more important for Sri Lanka.

To benefit from an export led growth model that is necessarily based on trade, it is important that Sri Lanka strengthens its competitiveness to promote trade and FDI, leverages on its locational advantage of geographical proximity to economic powerhouses, establishes the necessary conditions for a thriving knowledge economy, integrates productive local companies in global value chains and attains higher value addition in the manufacturing sector. This reform process will be key for Sri Lanka’s sustained economic prosperity.

With limited fiscal space and increasing expectations from the public, there is a need to improve the alignment of fiscal policy with development priorities, and improve budget credibility and resilience to shocks through better fiscal planning.

Through continued fiscal consolidation, it is important for the country to prepare for additional public spending on expanding pension coverage, and old-age health and long-term care in the medium to long term as Sri Lanka’s demographic transition advances.

Fiscal space is equally important to increase investment in human and physical capital, and the provision of other public goods to sustain growth in the medium term.

To consolidate gains in poverty reduction, a careful consideration of the distributional impact of tax and spending on poverty will make it possible to increase tax collection while offsetting the negative impact on the poor.

For example, it appears that little of the direct benefits of many current Value Added Tax (VAT) exemptions accrue to the poor. But removing them does come at a cost to the poor. So replacing them instead by targeted expenditure under the social safety net system could be a more efficient way of protecting the poor at a lower fiscal cost while simplifying the VAT system.

For example, it appears that little of the direct benefits of many current Value Added Tax (VAT) exemptions accrue to the poor. But removing them does come at a cost to the poor. So replacing them instead by targeted expenditure under the social safety net system could be a more efficient way of protecting the poor at a lower fiscal cost while simplifying the VAT system.

Ongoing efforts to reform the targeting system used by the flagship Samurdhi social protection programme will help in this regard. The increased fiscal space could be used for investment in public health and education provision, and infrastructure, to benefit poor areas.

Q: What is your take on the ease of doing business in Sri Lanka? Have we set realistic targets for improving our ranking?

A: The country has made progress in the ease of doing business over the years but others have done better.

While the target of moving up in the rankings from 110th to 70th position seems ambitious, what’s more important is to consistently continue to progress in reforms. Sri Lanka has already demonstrated its strong commitment to improving its business climate: a road map with clear objectives for reforms has been articulated for eight Doing Business topics while task forces are already working to implement action plans for reforms under their relevant areas.

It is a proven fact that unless the investment climate is favourable, investors will look elsewhere for options. This is also an important element to realise the trade potential through export led growth. Sri Lanka needs to assert its position firmly in the region and world in improving the business environment to be more competitive.

Undertaking reforms can be difficult. All opportunities for Sri Lanka to demonstrate that it can improve its ranking are in place. But to do this, it must stay on the reform path. Consistency and determination to deliver high quality reforms will earn miles. In addition, it is crucial to involve the private sector in reforms to create space for improvement.

As with all windows of opportunity, they are time bound. Inaction over a period of time – and more importantly, a lack of results – will hasten the window’s closure. Our assessment is that more can be done more rapidly.

But it is possible that at times, a country’s rating will fall even though it has carried out reforms. So it’s wise to review what the target reforms are and ensure that they too are included in the strategic review.

We don’t recommend that a country only works on reforms to be evaluated for the Doing Business ranking. Reforms are long term and have a cumulative impact by nature. A steady pace of creating a robust regulatory and institutional foundation will help Sri Lanka rise in ratings.

Q: How important is the Right to Information (RTI) Act?

A: The RTI Act can help citizens hold governments accountable and encourage them to participate actively in democracy. Sri Lanka’s RTI Act has one of the strongest legal frameworks in the world. Successful implementation of it will help build broad support for ambitious reforms.

When citizens feel they are being asked to contribute to the country’s development goals, and at the same time the government opens up and shares information on how it is performing, it enhances cohesiveness and support for tough but much needed decisions. Openness is not only important for these types of reform processes but for the government and environment in which it operates.

Q: In what key ways can citizens and institutions alike utilise the RTI towards national progress?

A: The RTI law can be a game changer in Sri Lanka’s path to prosperity if it’s used with a focus on development effectiveness. It is indeed one of the tools for all citizens to participate and influence the decision-making processes of the public sector.

Sri Lanka’s RTI Act is already being tested. Diverse requests that range from questions relating to how investments are made for the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) to how soil and sand mining permits have been allotted in districts such as Gampaha have been filed.

The private sector is also subject to and a beneficiary of the new RTI Act. In Sri Lanka, the strong emphasis on proactive disclosure of information is good news for the island’s economy. The data held by the government amounts to intangible assets that it is producing daily. By releasing it in a manner that can be easily used and reused by the private sector, you can reduce transactions costs for companies while increasing competition, transparency and innovation.

The private sector is also subject to and a beneficiary of the new RTI Act. In Sri Lanka, the strong emphasis on proactive disclosure of information is good news for the island’s economy. The data held by the government amounts to intangible assets that it is producing daily. By releasing it in a manner that can be easily used and reused by the private sector, you can reduce transactions costs for companies while increasing competition, transparency and innovation.

For example, local companies would benefit from having the same easy access to a consolidated database of national laws and regulations. Fiscal data – be it tax measures, budget allocations or tenders – could also be put to use by businesses. The same is true for transport data or anonymised household surveys. Granting the same access to all companies levels the playing field and fosters competition.

For example, in the European Union (EU), the directive on public sector information (PSI) has been used to support companies by encouraging the reuse of information that public bodies in the EU produce, collect or for which they pay. Under this directive, weather and mapping data was repurposed commercially by third party entrepreneurs for use in the GPS.

Public sector bodies that have drastically cut their charges for reuse have seen a dramatic increase in users.

For instance, in the case of the Danish Enterprise and Construction Authority (DECA), the number of reusers increased by 10,000 percent, leading to a reuse market growth of 1,000 percent over eight years. The additional tax revenue for the government is estimated to be four times the reduction in income from fees it would have charged for obtaining the data.

For instance, in the case of the Danish Enterprise and Construction Authority (DECA), the number of reusers increased by 10,000 percent, leading to a reuse market growth of 1,000 percent over eight years. The additional tax revenue for the government is estimated to be four times the reduction in income from fees it would have charged for obtaining the data.

Finally, both information infrastructure and processes will need to evolve to face the challenges that lie ahead. Nurturing citizen engagement policies, and encouraging petitions and public consultations will help strengthen the process, as well as close the feedback loop.

Going forward, implementation of the RTI Act will need to be complemented by grievance redressal mechanisms that empower citizens to take action based on the information they receive.

Q: What level of involvement does the World Bank have in the implementation of this act?

A: Sri Lanka owns one of the world’s most recognised RTI acts. The challenge is in the implementation.

The World Bank has experience working in other parts of the world, supporting the implementation of RTI laws. In Sri Lanka, the World Bank works closely with the RTI Commission to support implementation of the law.

In May, commemorating World Press Freedom Day, the RTI Commission released a Strategic Implementation Plan with support from the World Bank that will be implemented together with government and other development partners. It will include capacity development initiatives and systems to receive, track and respond to RTI queries.

Leave a comment