GLOBAL DEBT CRISIS

NO SILVER BULLET IN SIGHT

Samantha Amerasinghe reports on how countries are juggling a balancing act

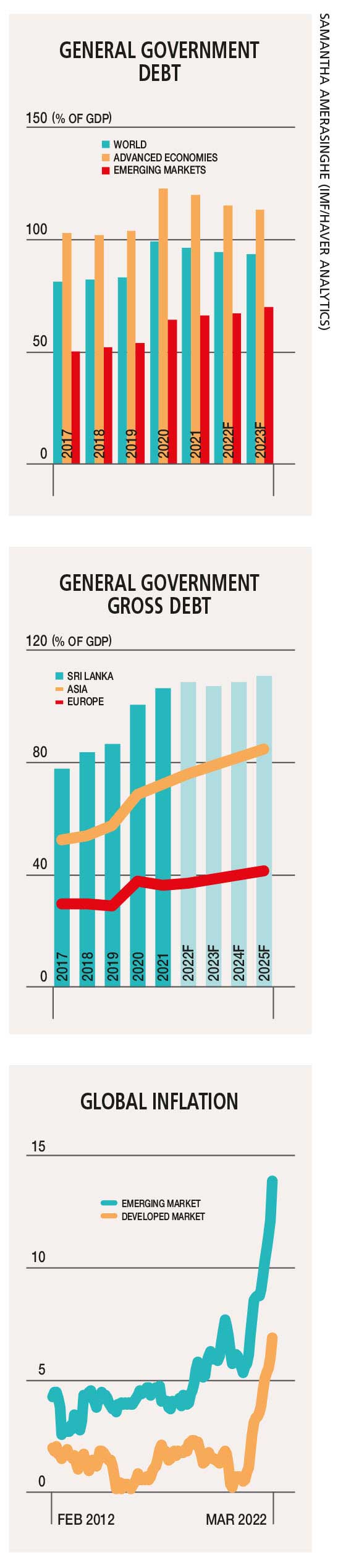

Debt in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) is at its highest level in half a century. The pandemic induced recession of 2020 led to the largest single year surge in global debt since at least 1970 with borrowings rising to US$ 226 trillion.

This spike came on the heels of a decade long global debt wave that has been the largest and most rapid since 1970.

Let’s assess the policy options for EMDEs such as Sri Lanka, which have debt trajectories that are proving to be unsustainable – given that global financial conditions have tightened in recent months.

There is no silver bullet to cope with the debt overhang – and no attractive or easy path to debt reduction. Nevertheless, it is imperative that policy makers strike a right balance in managing debt in the face of rising inflation.

Public debt now accounts for almost 40 percent of total global debt. The accumulation of public debt since 2007 is largely attributable to the two major economic crises that governments have faced.

First was the global financial crisis and then came the COVID-19 pandemic.

Government debt rose 19 percentage points of GDP in 2020 due to the pandemic, similar to the increase seen during the global financial crisis. However, the nature of the two crises is quite different with private debt jumping by 14 percentage points of GDP during the pandemic.

Government debt rose 19 percentage points of GDP in 2020 due to the pandemic, similar to the increase seen during the global financial crisis. However, the nature of the two crises is quite different with private debt jumping by 14 percentage points of GDP during the pandemic.

It was almost twice that which was seen during the global financial crisis since governments and central banks had previously supported further borrowing by the private sector, to help protect lives and livelihoods.

Emerging markets (excluding China) and low income countries accounted for small shares of the rise in global debt (around US$ 1-1.2 trillion each), which was mainly due to higher public debt.

As financing conditions the world over tighten with inflationary pressures becoming more acute following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the debt surge will amplify vulnerabilities. In most cases, high debt levels constrain the ability of governments to support recovery and the capacity of the private sector to invest in the medium term.

A crucial challenge is to strike the right mix of fiscal and monetary policies in an environment of high debt and rising inflation.

Central banks in developed economies are walking a tightrope as they attempt to tame the highest rate of inflation in roughly four decades against a backdrop of mounting geopolitical tensions, weakening world growth and highly volatile financial markets.

Debt dynamics differ markedly across countries.

In EMDEs, total debt reached 206 percent of GDP in 2020. And amid the worst recession since World War II and unprecedented fiscal stimulus, global government debt registered its fastest single year jump since 1970 to its highest level in half a century – 97 percent of GDP.

It reached 120 percent of GDP in developed economies. According to the Institute of International Finance (IIF), debt levels across emerging market economies have risen sharply over the past couple of years, growing to nearly 100 trillion dollars at the end of 2021 from less than US$ 65 trillion roughly five years ago.

Emerging markets and low income developing countries faced much tighter financial constraints but with large disparities across countries. Developing nations also had to contend with limited access to funding and often higher borrowing rates.

Meanwhile, developed economies were able to expand public and private debt during the pandemic thanks to low interest rates, the actions of central banks (including large purchases of government debt) and well developed financial markets.

Developed economies and China accounted for more than 90 percent of the US$ 28 trillion debt surge in 2020 – China alone accounted for 26 percent of the global debt surge.

So what are the conventional methods for dealing with extreme debt duress?

The two simplest methods include fiscal consolidation by cutting budget deficits (often referred to as ‘austerity’) and privatising government assets.

Alternatively, inflation, financial repression and debt restructuring can impose heavy economic costs, while wealth taxes or reforms to generate higher growth could face difficult practical and political obstacles. In EMDEs, greater uncertainty about prospects for growth and interest rates argues for heavy reliance on fiscal consolidation to lower debt.

Waiting to restructure debt until after a default occurs (as in Sri Lanka’s case) is associated with larger declines in GDP, investment, private sector credit and capital inflows rather than preemptive debt restructuring. Sri Lanka simply waited too long to engage with the IMF.

Nonetheless, even though the country has defaulted on its foreign debt obligations, seeking financial support from the IMF is the elixir the country needs – given that it must repay at least four billion dollars over the rest of 2022.

Though the IMF and World Bank had sounded alarm bells on this untenable situation, neither institution presented ambitious solutions to tackle debt problems. There’s no silver bullet to resolve the global debt crisis or Sri Lanka’s economic crisis for that matter.

Leave a comment