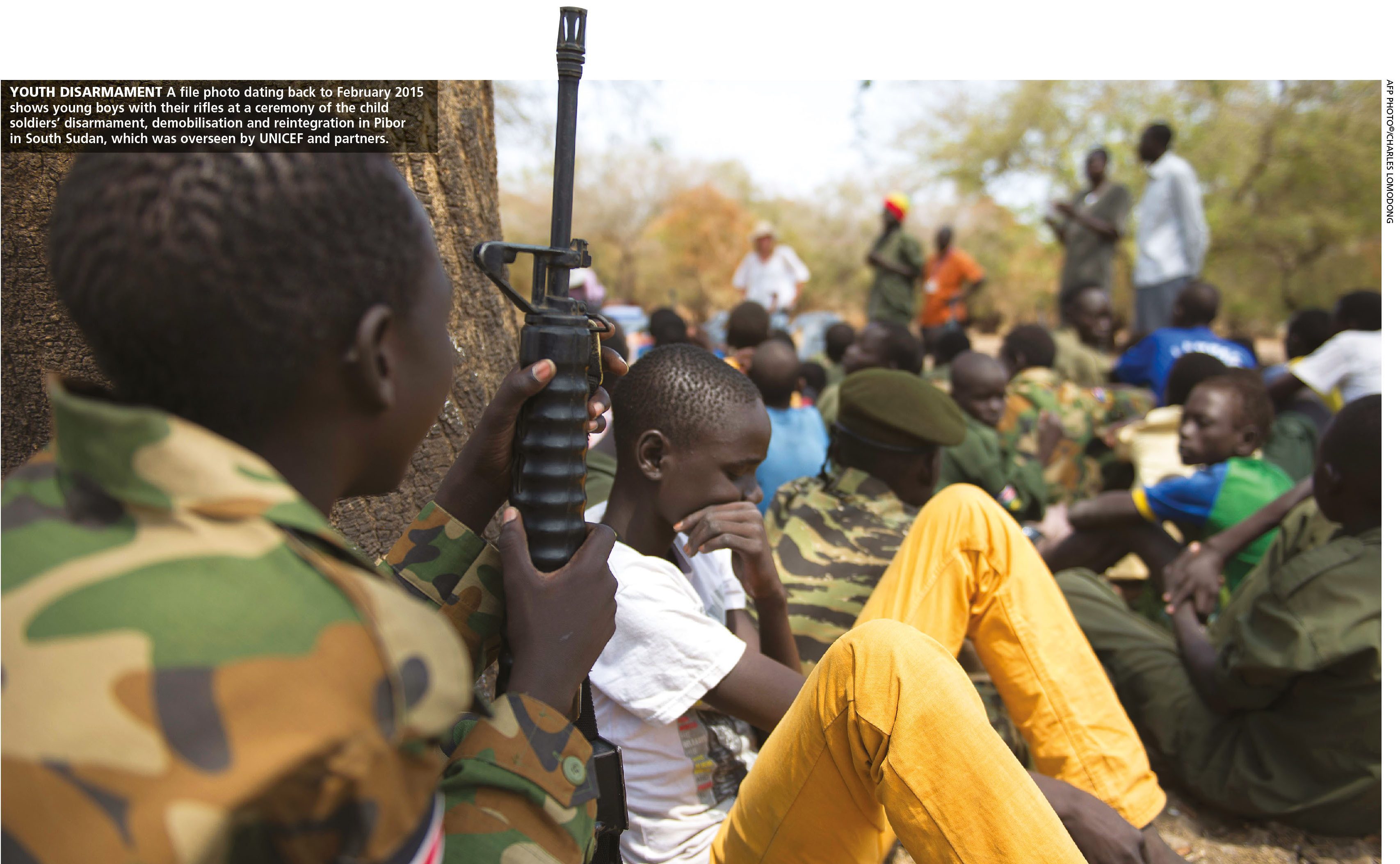

CHILDREN OF WAR

SHATTERED LIVES

Rajika Jayatilake believes the tragedy of child soldiers will rankle in humanity’s conscience for ever and a day

American author Dave Pelzer declared: “Childhood should be carefree, playing in the sun; not living a nightmare in the darkness of the soul.” Could there be anything darker for the soul of a child than having to don the mantle of being a child soldier?

And as Canadian humanitarian Roméo Dallaire said, “it may seem unimaginable to you that child soldiers exist and yet, the reality for many rebel and gang leaders, and even state governments, is that there is no more complete end-to-end weapon system in the inventory of war machines than the child soldier. Man has created the ultimate cheap, expendable yet sophisticated human weapon at the expense of humanity’s own future – its children.”

At least 300,000 children around the world are being robbed of a normal childhood and education, as armed conflicts selfishly deploy them as soldiers to kill and be killed. Some are as young as seven, and forced to fight on the front lines, join suicide missions, and work as messengers, lookouts and spies.

The former Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict Olara Otunnu once stated: “Compelled to become instruments of war, to kill and be killed, child soldiers are forced to give violent expression to the hatreds of adults.”

Militia groups target children for recruitment because they ‘cost less’ and are easier to control than adults.

Children are easy to brainwash with revenge, community identity and ideology, added to which they’re relatively fearless. And when they live

in vulnerable circumstances like extreme poverty and deprivation or are orphaned, they choose the struggles of the battlefield. The dark truth is that children replace adults who have died in combat. In recent times however, the world’s collective conscience has been pricked by this terrible crime against children and world leaders are focusing on it with greater intensity than in the past.

A meeting in the French capital in February last year marked the 10th anniversary of the Paris Principles and Commitments adopted during the ‘Free Children from War’ conference in 2007, which was organised by France and UNICEF.

Speaking at last year’s conference, the Executive Director of UNICEF Anthony Lake revealed that at least 65,000 children had been released by armed forces and groups during the past 10 years. However, he cautioned that the meeting was not only about what has been achieved but also to focus on what remains to be done “to support the children of war.”

Child soldiers are recruited by armed militias in Africa, South and Southeast Asia, the Middle East and South America. Some governments also recruit children under 18 to increase the numbers in their armed forces. However, most of the recruitment in the 14 countries on the UN’s ‘list of shame’ that commit “grave violations against children in armed conflict” is carried out by militia groups.

The 2017 UN annual report notes that the rights of over 15,500 children were violated in 2016 – including “shocking levels of killing and maiming, recruitment (as child soldiers) and denial of humanitarian access.” The Saudi Arabia-led coalition fighting in Yemen was recently added to the list.

Children born in conflict ridden nations are vulnerable to recruitment. Added to this, when all they have seen in their impressionable years is violence and more violence, they’re gradually desensitised. With few employment options available to them, they opt to join armed groups as their only route to safety and security. Furthermore, 30 percent of the world’s armed groups recruit girls.

Amidst the darkness of such grave abuses against innocent children, there’s the occasional ray of hope. The removal of the DRC’s military from the UN list of shame last year is recorded as the only delisting following Chad in 2014.

The DRC’s current national army, officially established in 2003, has been in constant conflict with the country’s several militias. With no known figures of child recruitment, human rights groups believe the numbers to be in their thousands. Nevertheless, the fact that the military has officially stopped using children lends hope to the belief that other nations like Colombia could be persuaded to follow suit.

Colombia’s peace deal with the revolutionary group FARC signed in November 2016 included the demobilisation of all child soldiers recruited by the guerrillas.

However, not all countries walk the talk.

Even though the Government of Afghanistan signed an agreement with the UN in January 2011, committing to protect children affected by armed conflict and disallow recruiting minors into its security forces, it has failed to do so to date. According to a recent report compiled by Newsweek, the US State Department admits there’s ongoing recruitment of child soldiers in Afghanistan, as well as in Iraq and Myanmar.

Countries in post-conflict situations understand the difficulty of reintegrating child soldiers into regular civil life. Having meted out violence to others, they’re unable to distinguish between right and wrong: they have lost their moral compass and social bonding; suffer from depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts; and are unable to return to childhood.

It is an unnecessary global tragedy created by bloodthirsty adults who should collectively make amends.