INNOVATION STRATEGIES

THE JOY OF DISCOVERY

Gloria Spittel presents the keys to the driver of business success – innovation

Whoever believes that innovation comes easily is either a creative genius or has been living in a vacuum – one in which every idea is the first great idea of its kind! Innovation is necessary but difficult to achieve.

Creative geniuses with fabulous ideas certainly exist but they do so in a world of heightened competition, scarce resources and fickle consumers. So the name of the game is not about innovating but how to innovate.

Everywhere, organisational top brass are demanding that employees innovate with new products, services, solutions or operational methodologies. But to do so simply by following a brief is a difficult task.

Over the years, since innovation became the driver of successful businesses, much has been discussed and written about developing an ecosystem, and the organisational culture and managerial leadership that would enable innovation to flourish.

PENCHANT FOR DISCOVERY However, organisational cultures and leadership styles that support and promote innovation must do so without stifling the impetus for innovation – discovery. In other words, innovation usually occurs when it can respond to a stimulus freely, which includes risk-taking, failure and a generally messy non-linear course.

But for companies, balancing these with organisational goals and scarce resources is a tricky business.

So it’s important to identify the different forms of innovation that an organisation could pursue. In identifying categories of innovation, companies can determine what’s appropriate (given any restrictions there may such as capacity, resources and time) as well as necessary for organisational development. Ideally, this identification process should occur before strategies are formulated to achieve innovation goals.

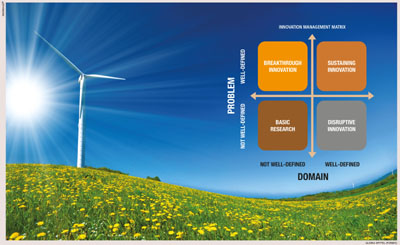

SETTING THE PARAMETERS According to the Innovation Management Matrix (IMM), there are four categories of innovation worth pursuing. But the first step in selecting what is suitable is to define the innovation problem (i.e. which problem the organisation wants to solve) and domain – who and what is best for developing the solution.

Once these parameters are known, they can be used to create a 2×2 matrix that consists of four types of innovation: basic research, breakthrough, and sustaining and disruptive innovation.

Basic research is the pursuit of discovering or innovating something completely new and unknown in the market. For this type of innovation, both the problem and domain are not well-defined. So it requires substantial investment, and usually collaboration with research and academic institutes. It could also be the riskiest of the four types of innovation but carries the potential to deliver an organisation-defining product or service.

Breakthrough innovation has a well-defined problem but the domain remains elusive. Companies that find themselves in this situation seek solutions beyond their organisational capacities and capabilities, and may co-opt other organisations into developing a solution.

In sustaining innovation, the organisation aims to sustain its innovative product or service year after year with new features or by improving what is available. This type of innovation could run the risk of being ignored by the market if the competition introduces a newer product or better features.

Organisations pursuing disruptive innovation could be on the verge of something big – as is the case with basic research. But even though the domain is well-defined, the lack of a clearly defined problem could lead to failure. To offset the high risk and capital incentive nature of disruptive innovation, organisations have begun to set up innovation labs to contain, test and build without the market fears of failure.

INNOVATIVE INITIATIVES There are other tools that help organisations innovate such as the Innovation Ambition Matrix (IAM) that is based on the Ansoff Matrix. They help organisations invest in innovative initiatives while balancing risk with reward.

The IAM plots a company’s products and services against its customer markets to produce three innovation strategies: core, adjacent and transformational. The core tactic optimises existing products by utilising available assets for an existing customer base. It is similar to the sustaining innovation of the IMM.

Meanwhile, the adjacent tactic builds on what the company does well, and expands to the next identifiable customer base through the introduction of products and services or by adding incremental changes. The key focal point here is the new customer base that will influence the changes the company would add on to its existing products.

Transformational tactics are similar to the disruptive or breakthrough innovations of the IMM, and would have an organisation developing new products and services for fresh markets. But to do this, organisations usually require additional assets and an appetite for risk.

THE CREATIVE FLUX It seems rather oxymoronic that a concept such as innovation, which at its heart has ‘the freedom to create’ etched across it, requires strategies for its development.

But without it, companies run the risk of being stuck in a creative flux with few product or service offerings to appease their boards and customers.

Perhaps when it comes to prioritising and utilising scarce resources, these strategies help businesses set the stage for innovation by identifying gaps and providing the necessities. At the very least, both IMM and IAM frameworks help conceptualise the elusive innovative streak that organisations desperately seek.