INFLATION OUTLOOK

EMERGING MARKETS ON EDGE

Samantha Amerasinghe examines the impact of inflation on emerging markets

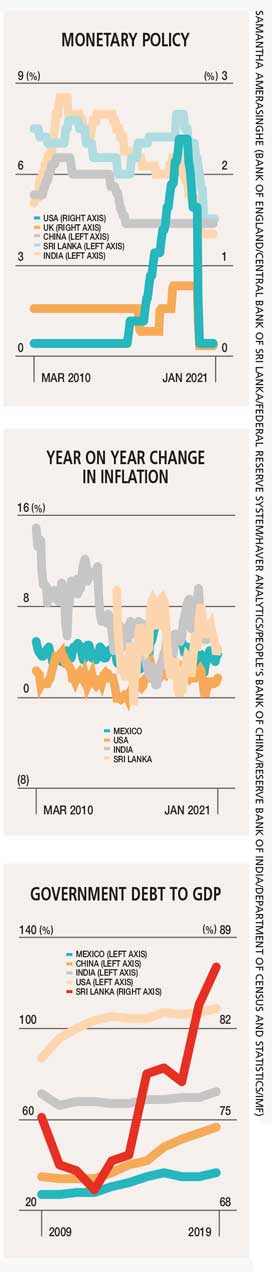

Is this the end of the era of low inflation in the global economy? Major central banks have responded aggressively to the economic impact of COVID-19, cutting policy rates to the zero lower bound and expanding balance sheets at an unprecedented pace.

Governments have also been quick to respond with substantial stimulus packages, which are much larger than those seen during the 2008/09 global financial crisis (GFC).

Governments have also been quick to respond with substantial stimulus packages, which are much larger than those seen during the 2008/09 global financial crisis (GFC).

The enormity of the US $1.9 trillion fiscal stimulus package recently signed into law in the US and the central bank’s endorsement of higher inflation – with its recent commitment to let inflation run hot to make up for past periods of undershooting its two percent target – has investors on edge.

Indeed, the sheer scale of the fiscal response has reignited the debate on whether following nearly three decades of easing, inflationary pressure is likely to rear its head again. As the economic recovery takes hold, it seems inevitable that inflationary pressures will reemerge over the next year or two but will it be a greater risk in emerging markets?

Since the GFC, major central banks have been increasingly worried about deflation rather than hyperinflation, maintaining very accommodative policies to reach inflation targets. Some argue that COVID-19 threatens to change this trajectory.

In fact, a view that has gained momentum among market participants is that high levels of monetary and fiscal stimulus will push inflation higher over the medium term. This is not shared by the US Federal Reserve – not at this juncture at least.

In fact, a view that has gained momentum among market participants is that high levels of monetary and fiscal stimulus will push inflation higher over the medium term. This is not shared by the US Federal Reserve – not at this juncture at least.

The Fed recently ramped up its expectations for economic growth to 6.5 percent for this year (up from 4.2%). However, it indicated that interest rate hikes are not likely through 2023 despite the improving outlook and a turn to higher inflation (to 2.4% versus its prior estimate of 1.8%) this year – a rise Fed officials say will be temporary.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell emphasised that even as the economy reopens from the devastating pandemic, it looks nothing like the one hounded by roaring inflation in the 1960s and ’70s.

Unlike in developed markets where structural matters like ageing populations support lower inflation, such factors are not in play in the emerging markets space. In emerging markets, the use of unconventional monetary policy (i.e. quantitative easing), dependence on commodities and the rise of the middle class could push inflation higher.

Job losses from rising deglobalisation (i.e. the supply chain disruptions and reshoring activity that has been exacerbated by the pandemic) could also weigh on inflation but may fade over the medium term.

However, of greater concern is the prospect of higher commodity prices – especially oil – as food and energy inflation with a weight of 30-60 percent is among the largest components of the CPI basket for most emerging markets.

Subdued crude oil prices kept inflation low in 2020, enabling emerging market central banks to pursue significant monetary easing but the weakness in oil markets is unlikely to last. Demand is likely to rebound strongly later this year as vaccine programmes accelerate – despite short-term issues in Europe – boosting travel and the wider economy.

Some bank analysts are predicting that the Brent oil price could even hit 80 dollars a barrel by mid-year. Furthermore, low and middle-income countries can run into problems quickly when trying to stimulate their economies unlike their developed counterparts. Central bank credibility and independence plays a significant role in ensuring that monetary and fiscal levers are optimised.

From a monetary standpoint, lowering interest rates can raise inflation and reduce the value of currencies, thereby making servicing forex debt more difficult and imports more expensive.

Therefore, central bankers are cautious about easing monetary policy too much in case it triggers higher inflation, which could force them to tighten policy.

For this reason and despite a severe recession taking hold, India has maintained its policy rate at four percent since May last year while headline inflation accelerated above the targeted band.

Fiscal capacity is one of the critical determinants of inflationary pressures in emerging markets. The lack of fiscal space has been one of the main factors driving the use of unconventional monetary policies (i.e. quantitative easing), which has led to an increase in asset purchases.

The less mature institutional frameworks in such markets – i.e. compared to developed markets – has increased the perceived risk among investors of debt monetisation, fuelling worries about higher inflation through excessive money printing and subsequent spending.

Consequently, most emerging markets have implemented relatively modest stimulus programmes.

This is because additional financing can be difficult to obtain if investors become concerned about debt levels no longer being sustainable. The IMF estimates that India’s fiscal stimulus will amount to only 1.7 percent of GDP while Mexico’s will be a mere 0.7 percent with gross government debt as a share of GDP rising in both countries by around 10 percent between 2019 and 2021.

The IMF suggests that it would take the world economy more than two or three years to return to 2019 GDP levels. Therefore, unless governments commit to sustained increases in fiscal stimulus, inflationary pressures will likely remain muted over the medium term. Nonetheless, it’s a riskier road ahead for emerging markets.

Leave a comment