INDIA AND CHINA COULD HELP COVAX FULFIL ITS VACCINE MISSION

- High-income countries are hoarding COVID-19 vaccines, while low and middle-income countries are struggling to gain access.

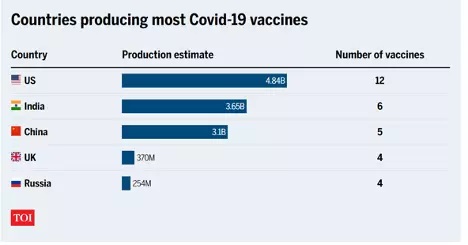

- India and China, producers of more than half of the global capacity of COVID-19 vaccines, must do more to share supply with COVAX.

- Equitable distribution of vaccines is the fastest route to global recovery: “No one is safe until everyone is safe”.

As we move into a second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, an overwhelming part of the world desperately awaits access to vaccines that hold the power to return life to a version of normal. The rapid speed of vaccine development is perhaps the most positive story throughout this pandemic, cutting the average development time from 5-10 years to less than one. The efficacy of these vaccines, despite the short development time, is nothing short of a scientific miracle. The distribution of vaccines within and among countries less so.

Scaling up production, distribution, and the actual administration of vaccines to patients, has proven to be as challenging as feared, plagued by delays and “vaccine nationalism”. In Jan 2021, when close to 40 million vaccine doses had been administered in high-income countries, one single low-income country had been provided access to a mere 25 doses.

Despite the fact that a large majority of people worldwide needs to be vaccinated to eradicate the virus, we have seen hoarding by high-income countries – the US has secured close to 3 billion doses (or 8 times the total population) – while most low and middle-income countries (LMICs) are far from the 2021 target of 20% of the population. In addition to affecting access timescales, the hoarding has also driven up costs, whereby South Africa and other countries have had to pay up to double the price than that of the EU.

Foreseeing this course of events, the World Health Organization (WHO) created COVAX (COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access) – an initiative aimed at ensuring fair and equitable access to vaccines in all countries, initially focusing on healthcare workers and risk groups representing around 20% of the total population across LMICs.

As well as reducing the tragic loss of life and helping to get the pandemic under control, worldwide access to vaccines would prevent the loss of $375 billion to the global economy every month. Yet, the US under Trump did not participate in COVAX. Indeed, the coalition has been struggling to access the necessary funding – at the end of 2020 it had a funding gap of $4.3 billion.

The Biden administration has since announced that the US will join COVAX and increase its funding, but the damage to early momentum and financial strength will be hard to undo. Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of WHO, has slammed high-income countries, calling the hoarding “A catastrophic moral failure,” that will “prolong the global pandemic.”

With the slogan, “No one is safe until everyone is safe” he has repeated the plea to instead sell the global vaccine production to COVAX at fair prices, which will in turn allocate vaccines based on needs and order of priority. So far, the EU and US have pledged to share all excess doses with COVAX to avoid waste, but only after internal demand has been met. Realistically, that will not happen before 2022.

Can the East help COVAX fulfil its mission?

India and China together represent more than half of the total global vaccine production. Together, they are estimated to produce close to 7 billion doses during 2021.

So why are none of the largest producers of vaccines – both LMICs – walking the talk and selling the majority of their capacity to COVAX at a fair price? Doing so would offer multiple benefits:

- Significantly contribute to COVAX’s goals of reducing death and suffering as well as improving the global economy.

- Put pressure on the EU and US to follow suit; if LMICs can afford to share, how can high-income countries justify not doing the same?

- Support China in its narrative of being the solution rather than the cause of the pandemic. It would also add credibility on the global humanitarian stage, including their “vaccine diplomacy” initiative, which to date appears to be no more than the West’s commitment to share excess vaccines once internal demand has been met.

- India would cement its position as the “pharmacy to the world”, emerging as the humanitarian superpower of the Global South, as well as generating international goodwill for decades to come.

According to a study by the Center for Global Development, it will take an estimated 2-4 years before the entire world is vaccinated. And those numbers assume that funding can also be secured for the larger non-risk group – healthy adults –through COVAX or other initiatives.

Where does that leave LMICs when it comes to health are as well as returning to normal life? Not only is it a matter of immediate life and death, it is also about competitiveness in the global economy, which in turn will affect the lives of billions of people.

The World Bank estimates that temporary school closures in Sub-Saharan Africa to date will cost close to $500 billion in future earnings, close to $7,000 per child or more than 4 years of GDP per capita in the region. And in the end, what was the value of achieving a miracle on the development side if the deployment of vaccines takes years? As Dr. Peter Singer, Special Adviser to WHO Director General puts it, “We will each need to explain to our children and grandchildren what we did to meet this challenge together.”

With such high stakes, China and India face a once in a generation opportunity to act as the leaders they aspire to be. We therefore urge them to sell the majority of their vaccine capacity to COVAX for fair and equitable distribution.