DISASTER MANAGEMENT

BETWEEN A DELUGE AND DROUGHT

Zulfath Saheed highlights Sri Lanka’s priorities for disaster management

The seemingly all-knowing Google defines a natural disaster as “a flood, earthquake or hurricane that causes great damage or loss of life.” In the case of Sri Lanka, floods and landslides are among the most common natural disasters – as witnessed in the second half of May when torrential rains led to a more heightened version of events that were experienced around the same time last year.

But what needs to be understood is that the term ‘natural disaster’ can be somewhat misleading. This is because the negative outcomes of certain weather related events could be managed through proper planning and preparation, which also includes a focus on curbing human activity that precipitates adverse conditions.

FLOOD OUTCOME The southwest monsoon was held responsible for this year’s floods, which began in mid-May and were intensified by Cyclone Mora that made landfall in Bangladesh.

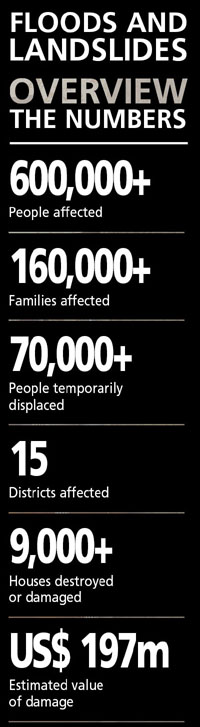

Fifteen districts were affected by the floods while over 200 people were killed and more than 90 went missing. By early June, it was reported that more than 600,000 people were affected by the floods with several thousand houses partially damaged and close to 3,000 homes being completely destroyed. Galle, Kalutara, Matara and Ratnapura were among the worst affected districts.

DISASTER RESPONSE Sri Lanka’s tri forces that include army, navy and air force personnel were heavily involved in the flood rescue operations. Meanwhile, foreign nations contributed to response efforts primarily in the form of funds and essential relief items.

Community involvement was also extensive with organisations and citizens alike pitching in to help victims. In particular, they leveraged on the internet and mobile apps to stay updated, coordinate relief efforts and channel resources where they were most needed.

But as has been the case in the past, public officials and institutions tasked with disaster management – including the minister in charge and the Disaster Management Centre (DMC) – came in for flak. The critics cited limited preparedness on their part to manage the disaster.

And indeed, they have been roundly criticised for initiating inquiries to identify shortcomings only after the event.

FUTURE EFFORTS Since the floods in mid-May, the DMC has reportedly sought to revamp procedures to issue early warnings. In addition, the government has inked a deal with Japan to install new weather radar stations and stated that it would establish up to 100 disaster evacuation centres across the island.

The challenge then would be to ensure that these commitments are seen through to fruition and not simply forgotten once the hype has died down. It is also important to ensure there is proper coordination between the various officials and state agencies involved – an area that has been found wanting in the past.

REGIONAL EXAMPLE Amid Cyclone Mora’s relatively rapid intensification, Bangladesh’s authorities exemplarily carried out evacuations in preparation for the storm.

Maritime weather alerts were issued to the ports of Chittagong, Cox’s Bazar, Mongla and Payra in anticipation of a 1.2 to 1.5-metre storm surge. All flights out of the Shah Amanat International Airport in Chittagong were suspended and throughout the city, 500 shelters were opened.

The Bangladeshi authorities attempted to evacuate one million people prior to the cyclone’s landfall. And a total of 500,000 people had managed to move out of coastal areas before the storm made landfall on 31 May. Nine people were reported killed across Bangladesh, mostly due to falling trees.

DROUGHT IMPACT While much of the focus has been on floods and landslides, one can’t afford to forget that a drought lingers in the northern regions of the island. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations estimates that the drought is likely to lead to the rice harvest this year being at its lowest level in a decade.

The DMC has stated that more than a million individuals in 15 districts are being impacted by dry weather conditions – Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura, Puttalam and Vavuniya are considered to be the most severely affected by the prolonged drought.

More than Rs. 40 million has been spent on relief activities for the victims and some 200 bowsers have been used to distribute drinking water to the affected public, according to the DMC.

SAFETY MEASURES Between a deluge in some parts of the island and an absolute lack of water in others, Sri Lanka has much to deal with on the climate front.

In a step forward in April last year, a Natural Disaster Insurance Scheme was implemented through the National Insurance Trust Fund (NITF) to ‘protect [the] entire country against natural disasters.’ It covers lives and properties for up to 2.5 million rupees in respect of damages caused to property and contents due to cyclones, storms, tempests, floods, landslides, hurricanes, earthquakes, tsunamis and similar natural perils but excludes droughts.

Overall, as much as being in the hands of the weather gods, the people of this country need the help of appointed authorities to mitigate the tragedies caused by both floods and drought.