TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION

THE TIME TO HEAL IS UPON US

Rajika Jayatilake learns valuable lessons on reconciliation from Rwanda and South Africa

It is ironic that in a world that’s increasingly becoming a global village, it is harder to find truly global citizens like American union leader Eugene Victor Debs who said: “I have no country to fight for; my country is the Earth and I am a citizen of the world.”

People, communities and nations are territorial and self-seeking; their lust for power and money leading in extreme cases to horrifying tragedies. South Africa and Rwanda are two cases in point: even decades later, these societies have yet to heal completely after apartheid and genocide respectively. South Africa held its first democratic election on 27 April 1994, breaking from the institutionalised racial segregation and discrimination practised since 1948.

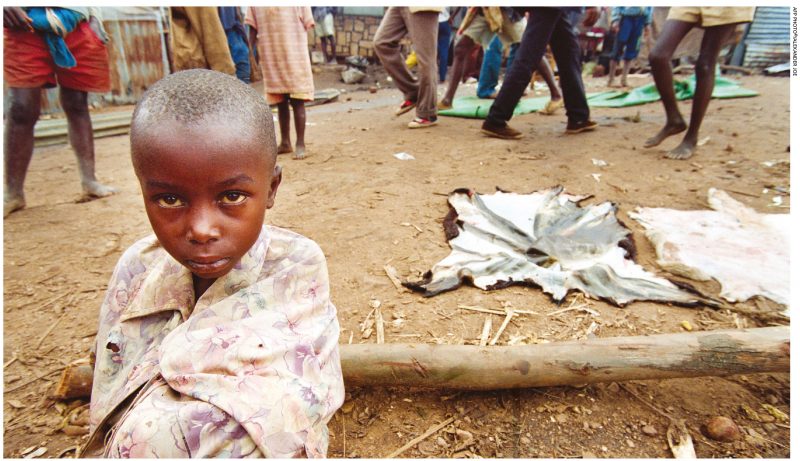

In Rwanda on 7 April 1994, its Hutu majority began indiscriminately slaughtering the Tutsi minority. During a 100 day holocaust, almost a million people were killed and around 250,000 women raped.

Subsequently, both countries desired reconciliation.

However, as American writer and historian Timothy B. Tyson has explained, “if there is to be reconciliation, first there must be truth.” Therefore, South Africa set up its Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to deal with human rights abuses under apartheid; and Rwanda launched the Gacaca Community Courts, which is considered as being one of the most far-reaching global justice systems established in any post-conflict scenario.

Through Gacaca, which represents a precolonial process for justice in Rwanda, individuals had the opportunity to confront each other and talk about the respective tragedies that had traumatised them in 1994. And so began the process of hearing and healing.

South Africa’s TRC focussed mainly on recording human rights abuses and seeking the truth. The Institute for Justice and Reconciliation that resulted from the work of the TRC realised that to reach the core of reconciliation, it was also necessary to focus on social justice and equality towards all communities – and not only truth.

The institute’s annual reconciliation barometer recognised that South Africans were increasingly seeking economic justice over all else. The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), a revolutionary socialist political party launched in 2013 and headed by Julius Malema, had promised to redistribute South Africa’s ‘stolen land’ and other resources, provide equal access to education for all, nationalise mining and banking, double welfare grants and increase the minimum wage.

Only recently however, EFF supporters vandalised a Swedish clothing store chain in South Africa over an allegedly racist jumper advertisement. The horrors of apartheid still haunt South Africa in different ways.

An active member of the ANC, Tiisetso Makhele believes that many South Africans feel short changed as the government has not moved beyond TRC initiatives. He says that perpetrators of apartheid crimes continue to thrive as modern-day heroes while victims and their families still await justice.

In a report titled ‘Apartheid Grand Corruption: Assessing the Scales of Crimes of Profit in South Africa from 1976 to 1994,’ South Africa’s Institute for Security Studies exposes how property theft in the country began with the arrival of European settlers in the Cape back in 1652.

This continued with large companies joining hands with successive colonial regimes to grab land from South Africa’s indigenous people. Such companies offered no compensation to the people but simply continued their exploitation. A law vital to apartheid known as the Native Land Act was passed in 1913, allocating only about seven percent of arable land to Africans, leaving more fertile land to whites and enabling the eviction of the natives from their traditional homelands.

However, in South Africa as well as in Rwanda, reconciliation was recognised as more complex than simply recording the truth, setting up commissions or conducting trials. Justice could not be traded for the truth – and without justice, there was no hope for reconciliation.

In Rwanda, the Gacaca courts had to grasp the truth of what had happened during the genocide. They processed about 60 million pages and more than 8,000 audiovisual recordings from 1,958,634 cases.

By the time the genocide ceased in July 1994, Rwanda lay in ruins. The survivors and killers had to rebuild their devastated lives anew by working side by side.

To prevent more violence, Gacaca sessions were organised in every community in Rwanda. They were led by judges from these communities. Once cases were heard and judged, the accused had to engage in community service such as rebuilding roads and people’s houses.

Furthermore, widows of perpetrators and victims alike worked together in business ventures or self-help cooperatives, engaging in shared livelihood activities. This helped start the healing of deep wounds created by the genocide. Rwandans realised that change at a systemic level was essential for reconciliation.

Rwanda in particular has become an effective model to follow for countries seeking reconciliation. Rwandans abandoned the colonial classification of Hutus and Tutsis; they now consider themselves Rwandans, as they move forward with commitment to move past their national tragedy – together.