OUTLOOK FOR THE GLOBAL ECONOMY AND POLICY PRIORITIES

The 2020s: Turbulent, Tepid or Transformational? Policy Choices for a Weak Global Economy

Speech by IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva

April 11, 2024

As prepared for delivery

Thank you, Fred for your kind introduction, and my thanks to you and the staff of the Atlantic Council for hosting this event. Like the IMF, the Council is an institution grounded in the belief that dialogue and cooperation can build a more prosperous world.

We also share some DNA. Secretary Dean Acheson, who co-founded the Atlantic Council, was also present at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944 which gave birth to the IMF and World Bank.

Reflecting on his years in public service, Acheson later wrote that: “The simple truth is that perseverance in good policies is the only avenue to success..."[1].

In a world of more frequent shocks and heightened uncertainty we need good policies more than ever.

Making the right policy choices will define the future of the world economy. It will define how this decade is remembered — will it go down in history as ‘the Turbulent Twenties’, a time of disturbance and divergence in economic fortunes; the ‘Tepid Twenties”, a time of slow growth and popular discontent; or ‘the Transformational Twenties’, a time of rapid technological advancements for the good of humanity?

Let me start with where we are today.

You will see in our World Economic Outlook next week that global growth is marginally stronger on account of robust activity in the United States and in many emerging market economies. Sustained household consumption and business investment and an easing of supply chain problems helped. And inflation is going down.

The resilience of the world economy, mostly due to sound macroeconomic fundamentals built over the last years, is helped by strong labor markets and an expanding labor force. The strength of labor supply is partly due to immigration, which has been especially helpful in countries with aging populations.

Overall, based on the data it is tempting to breathe a sigh of relief. We have avoided a global recession and a period of stagflation—as some had predicted.

But there are still plenty of things to worry about.

The global environment has become more challenging. Geopolitical tensions increase the risks of fragmentation of the world economy. And, as we learned over the past few years, we operate in a world in which we must expect the unexpected.

The sobering reality is global economic activity is weak by historical standards. Prospects for growth have been slowing since the global financial crisis. Inflation is not fully defeated. Fiscal buffers have been depleted. And debt is up, posing a major challenge to public finances in many countries.

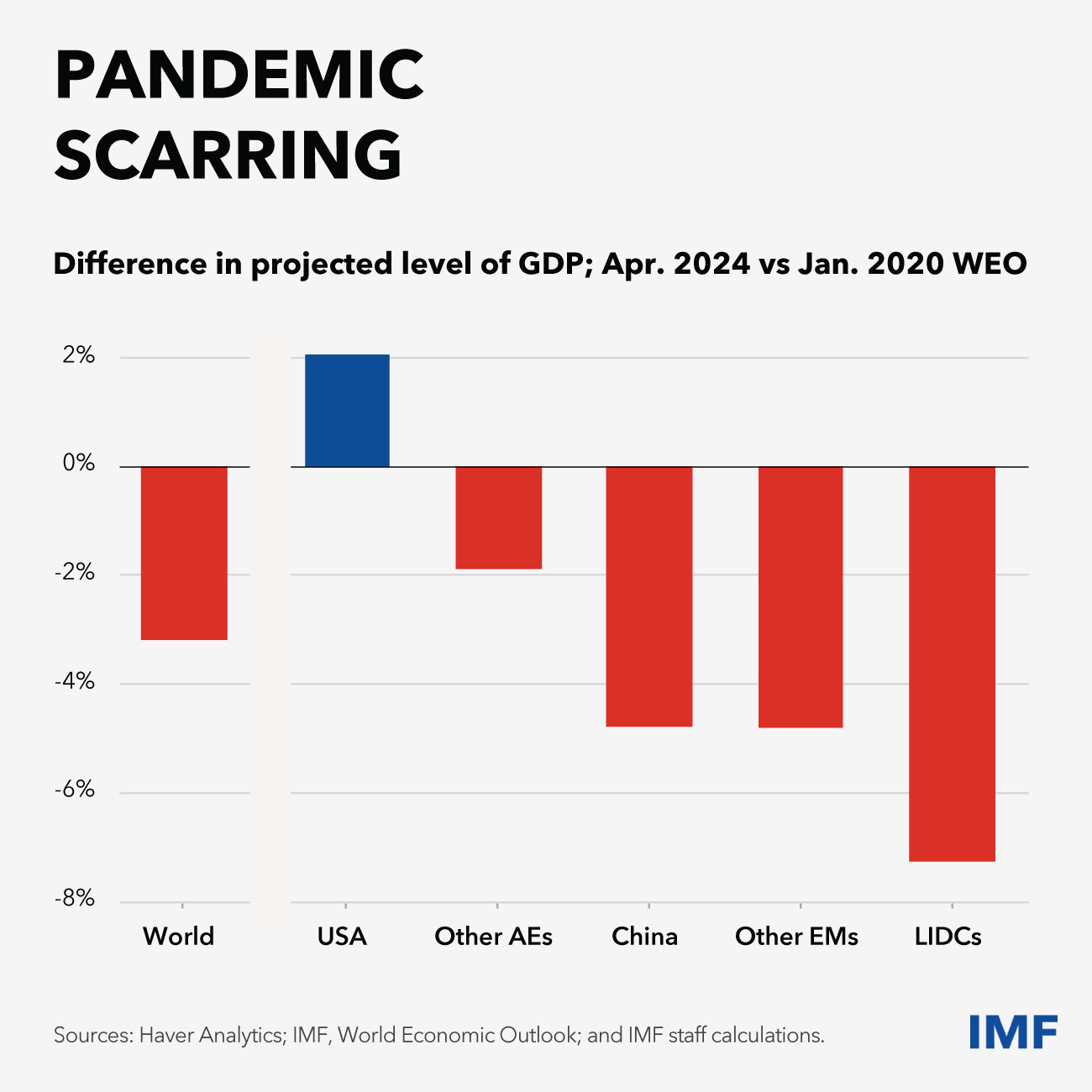

The scars of the pandemic are still with us. The global output loss since 2020 is around $3.3 trillion, with the costs disproportionately falling on the most vulnerable countries.

And we see a growing divergence within and across country groups.

Among advanced economies, the US has experienced the strongest rebound, helped by rising productivity growth. By contrast, activity in the euro area is recovering much more gradually, reflecting the lingering effects of high energy prices and weaker productivity growth.

Among emerging market economies, countries like Indonesia and India are faring better.

But the most striking divergence is for low-income countries for whom scarring has been the most severe. Among these nations, fragile and conflicted-affected economies are bearing the heaviest burden.

Beneath it all, the primary driver of weaker growth is a significant and broad-based slowdown in productivity. Our analysis shows it accounts for over half of the growth slowdown in advanced and emerging economies, and nearly all in low-income countries.

As a result, our medium-term outlook for global growth remains well below its historical average—just above 3 percent.

Without a course correction, we are indeed heading for ‘the Tepid Twenties’ – a sluggish and disappointing decade.

At this juncture, policymakers face a choice.

They can avoid difficult decisions and try to muddle through with less-than-good polices.

Or they can make another choice. They can follow Acheson’s advice and choose good policies: deal decisively with inflation and debt; and promote economic transformation to boost productivity, inclusion, and sustainable growth.

What we need is the ‘Transformational Twenties'.

But first thing first: we need to bring back price stability.

This is the task of central bankers, many of whom are carefully calibrating this important policy choice—when to cut interest rates and by how much.

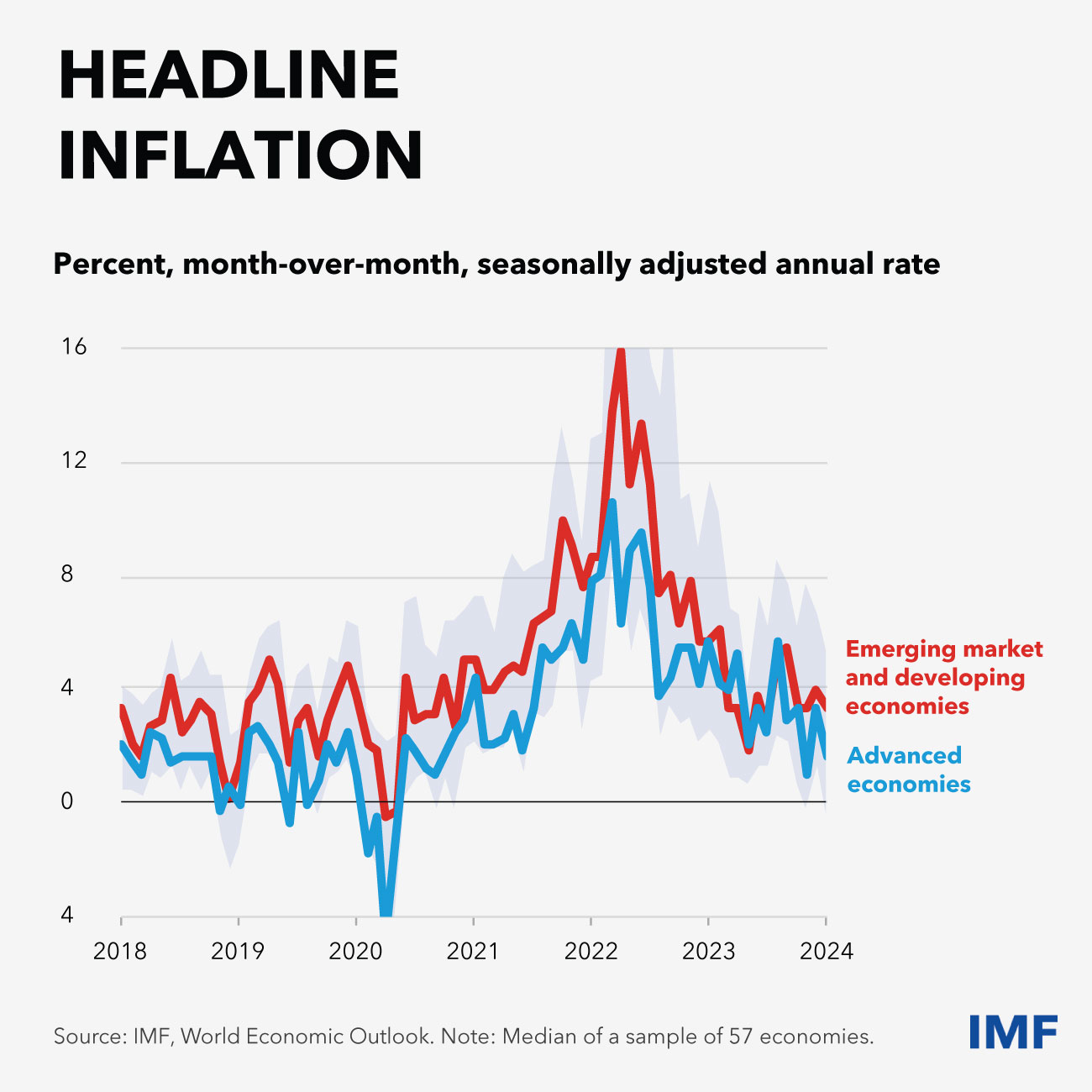

We have seen what good policy can achieve since inflation peaked in mid-2022. In the final quarter of 2023, headline inflation for advanced economies was 2.3 percent, down from 9.5 percent just 18 months earlier. For the median emerging market and developing economy, inflation declined to 4.1 percent.

We expect the trend to continue in 2024, creating the conditions for major advanced economy central banks to begin cutting rates in the second half of the year.

But the pace and timing of the monetary pivot will vary. Some central banks have already begun to loosen, mostly in emerging markets where inflation was tackled early. But elsewhere—primarily in advanced economies—they are still holding off for now. They must carefully calibrate their decisions to incoming data.

On this final stretch, it is doubly important that central banks uphold their independence. As we know, policy credibility is vital in the fight to restore price stability.

Where necessary, policymakers must resist calls for early interest rate cuts. Premature easing could see new inflation surprises that may even necessitate a further bout of monetary tightening. On the other side, delaying too long could pour cold water on economic activity.

Second, time has come to rebuild fiscal buffers.

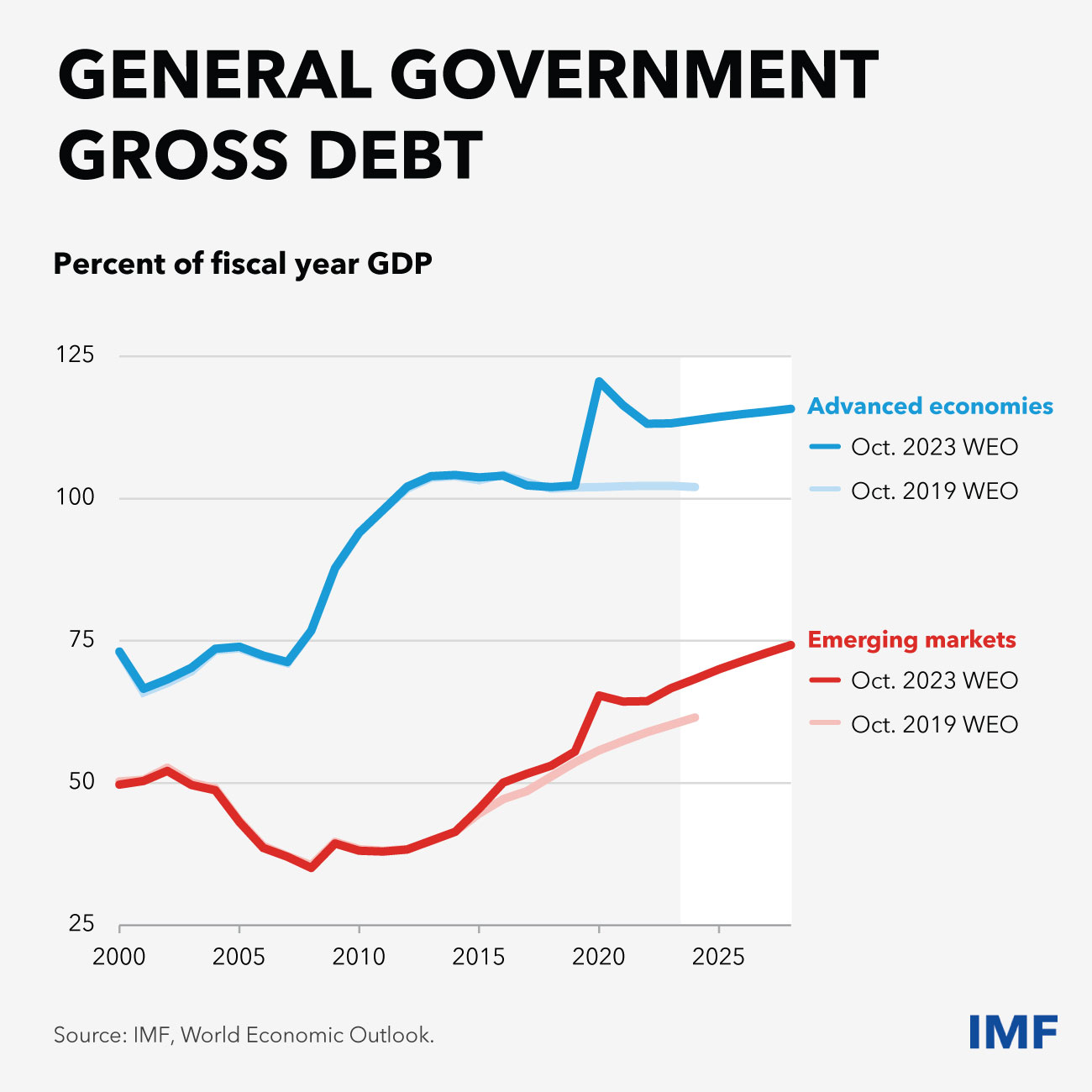

Over the past couple of years, we have advocated for fiscal policy restraint to support central banks as they fight inflation. A focus on fiscal policy is now warranted in its own right. Fiscal buffers are exhausted and debt levels in most countries are simply too high.

The trend of rising debts began more than a decade ago—during a prolonged period of very low interest rates. The pandemic necessitated an unprecedented fiscal response to protect lives and livelihoods. Debt surged even more.

Now, we are in an era of far higher interest rates. This is pushing up the cost of servicing debt.

In advanced economies, excluding the US, interest payments on public debt will average about 5 percent of government revenues this year.

But the cost of servicing debt is most painful in low-income countries. Their interest payments are set to average about 14 percent of government revenue—roughly double the level from 15 years ago.

For most countries, prospects of a soft landing and strong labor markets mean there is no better time to act: to reach sustainable debt levels and build stronger buffers to cope with future shocks.

For some, delay is simply not an option: consolidation must start now to avoid tipping into debt distress.

And for the handful of countries already in debt distress, restructuring may be necessary. The G20 Common Framework can help. Zambia recently finalized its agreement with bondholders, complementing the restructuring with official bilateral creditors—bravo!

We must build on lessons learned to improve the debt restructuring process. During the Spring Meetings, we will again convene our Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable. Our goal is to bring further clarity on “comparability of treatment” among different creditor groups and to establish clear and predictable timelines for debt restructuring.

For all countries, rich and poor, fiscal prudence is hard. This is especially true in a year with a record number of elections and at a time of high anxiety due to exceptional uncertainty and years of shocks.

In fact, our forecasts show deficits will still be too high to stabilize debt in over one third of advanced and emerging economies, and in more than one quarter of low-income countries.

This is why we advocate for adopting credible medium-term fiscal frameworks as the ultimate ‘good policy’ choice for countries.

We also recommend more focus on closing tax loopholes, strengthening tax collection, and improving the quality of public spending. Fiscal strength allows countries to support the most vulnerable parts of society and to invest in a better future.

This brings me to the third priority: policies to reinvigorate growth.

Lifting up growth prospects is paramount to improve living standards and strengthen economic resilience. It requires eliminating constraints to economic activity and creating opportunities to boost productivity growth.

Foundational reforms — strengthening governance, cutting red tape, increasing female labor market participation, improving access to capital — all have a role to play. Across emerging and developing countries, a well-sequenced package of reforms could lift output by 8 percent in four years.

Even more can be achieved with policies to encourage economic transformation — to speed up the green and digital transition. How well we handle them will define the legacy of this decade.

This is particularly important for the green transition. How quickly we advance it will have tremendous significance for whether we succeed to tame climate risks. But the shift to a climate friendly economy goes beyond managing risks. It also offers tremendous opportunities for investment, jobs, and growth.

We are already witnessing the economic, health and environmental benefits of transformative investments—including in renewable energy, electric mobility, and ecosystems restoration. For every $1 spent on fossil fuels, $1.7 is now spent on clean energy. Five years ago, this ratio was 1:1. But robust policies and institutions are needed for a stable and encouraging investment climate and to tackle a broad range of market failures.

Technological advancements affect many sectors of the economy—from manufacturing to healthcare and financial services. We have been transitioning to a new digital economy, and now AI is likely to dramatically accelerate the fourth Industrial Revolution.

This brings huge potential benefits but also risks. A recent IMF study shows that AI could affect up to 40 percent of jobs across the world and 60 percent in advanced economies. It could enhance workers’ productivity but also threaten some jobs. Investing in digital infrastructure and skills, as well as in strong social safety nets, will determine the pace of AI adoption and its impact on productivity.

Both the climate and the digital transformation require coordinated global efforts to manage risks and capture the benefits they create.

And this is my final point—cooperation on policies matters for the world.

The pandemic, wars, and geopolitical tensions have changed the playbook for global economic relations. Policymakers are looking to strike a balance between efficiency and security, between cost considerations and resilience in supply chains. There are already signs that trade relations are being re-shaped.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, trade growth between economies in politically distant blocs has slowed by 2.4 percentage points more than trade among those that are more closely aligned.

As trade flows are re-routed, ‘connector’ countries may benefit. But supply chains are lengthening, with potential costs at each step.

And industrial policies are back on the agenda—with new analysis showing more than 2,500 policy interventions worldwide last year. China, the EU, and US account for almost half of the total.

How should we think about these measures?

In short, if there is a market failure that is being addressed—such as accelerating innovation to address the existential threat of climate change—there is a case for government intervention, including through industrial policy.

If there is no market failure, there is a need for caution. The case for government intervention is much weaker. Some of the measures announced or implemented last year were not always clearly related to market failures.

IMF staff has stepped up work in this area because more data, analysis and dialogue are needed to avoid costly mistakes.

More broadly, we advocate for more trade and cross-border investment flows to increase productivity and address global challenges. And for more attention to how the benefits from trade and investment are shared in society. We must avoid past mistakes when the negative impact of globalization on some communities was ignored and led to backlash against an integrated world economy.

Throughout our history, the IMF has been and remains a transmission line for good policies and a place for economic cooperation.

In a fast-changing and more turbulent world, bringing countries together to tackle challenges and pursue opportunities is more important than ever.

When the world was hit by the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis, the IMF acted decisively to provide financial and policy support to our members.

We have also stepped up our efforts to help countries deal with transformational challenges such as climate change and the digital transition—with new analysis, new partnerships, and new instruments. For example, we now have 18 countries using our new Resilience and Sustainability Trust.

And just as countries need to build resilience to deal with future shocks, so too must the IMF.

We are already doing it.

Our members have supported a fifty percent increase in our permanent lending resources. And more capacity to provide financial support to our poorest members.

We have just reached the target for building up our own financial buffers, so we can be a reliable anchor for countries experiencing balance of payment shocks. We are now directing our attention to how to make better use of our balance sheet to ensure we are well-positioned to continue to help our members.

This is a fitting note on which to conclude. Just as our balance sheet represents the collective financial strength of our members, our Spring Meetings next week represent our collective commitment to cooperation and international dialogue.

So, as we gather in Washington, we have what Acheson described as a fundamental choice: “between meeting the problems with which the world will be faced… through methods of international cooperation…, or …each nation’s relying on its own resources and its own strength and going its own way in the world.”[2]

Working together is the choice of good policies.

The choice that will deliver the growth, jobs, and prosperity people aspire to — everywhere.