Is India the answer to Netflix’s troubles?

Netflix has launched is cheapest subscription plan – a mobile-only service for Indian users. The BBC’s Joe Miller finds out if India can solve the company’s financial woes.

In his 20 years as an entertainment journalist, Rohit Khilnani has seen hundreds of Bollywood stars vie for the attention of India’s gigantic film and TV audience. But it was the unexpected appearance of Brad Pitt at a Mumbai hotel in 2017 that made him realise America was serious about getting in on the act.

Pitt was among the first US stars to promote a movie – in person – in India. Christian Bale and Will Smith followed closely on his heels. Strangely, they weren’t the emissaries of giant studios such as Warner Brothers or Sony. Instead, they had come at the behest of a new media titan – Netflix.

The California-based streaming giant’s interest in India was put into sharper focus last week, after it reported a loss of 126,000 paying customers in the US, its home market.

As Netflix’s stratospheric stock price took a dive, the company also announced a cheaper, mobile-only subscription plan in India. At 199 rupees ($2.8; £2.2) a month, it’s priced to make inroads into a country, which chief executive Reed Hastings has half-seriously suggested could be the source of Netflix’s “next 100 million” subscribers.

But despite pouring money into Indian-made and original titles such as Sacred Games, Chopsticks and Lust Stories, Netflix’s footprint in India is relatively small.

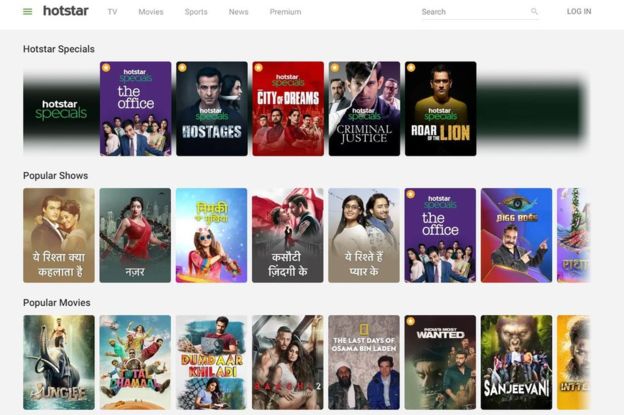

In a country of 1.3 billion people, it’s estimated that the company has between four and six million customers. By comparison, the homegrown (but Disney-owned) rival Hotstar boasts 300 million monthly active users, according to consulting firm RedSeer.

India is a “highly price sensitive market”, explains Rajib Basu, a partner at consulting firm PwC India. He says Netflix has thus far targeted a limited sub-section of “very educated, suave Indian consumers, who have a liking for international content as well as some original [Indian] content in English in Hindi.”

In a country that offers cable connections and mobile data at rock-bottom prices, and uses advertising to subsidise cheap subscriptions, Netflix had hoped its highly-produced titles would stand out, and convince viewers to swallow higher costs.

By contrast, Hotstar lured customers with live cricket matches, and Amazon offered free delivery as part of its Prime content package. The market is also peppered with dozens of smaller, specialist providers, that are sold as part of a bundle with mobile phone contracts.

But unlike North America and Europe, India is by no means a saturated market – and with its almost insatiable appetite for original content, enormous rewards await the companies that eventually emerge victorious in the war for eyeballs.

Consulting firm EY estimates that digital subscriptions in India grew by some 262% last year, to a total of INR14.2 billion ($205m). That expansion, EY found, was driven largely by sign-ups to video platforms – a trend that is expected to be supercharged by the arrival of 5G connectivity.

There is plenty of room for new providers too. Consulting firm BCG has calculated that Indians spend just 4.6 hours each day consuming media (including print, TV, radio, digital), far behind Americans, who spend an average of 11.8 hours.

The key to boosting those numbers, for Netflix or its rivals, “is going to ride on the further penetration of tier two or tier three cities”, PwC’s Mr Basu maintains. In those places, he explains, high-speed broadband and cable TV are not as pervasive, but smartphones are ubiquitous.

“I would doubt if Netflix would achieve [their expansion goals] by remaining in the market that they are,” he says.

“They will have to keep on churning out shows like Sacred Games, but they need more local language content too.”

Rohit Khilnani, who currently works for the news channel NDTV, agrees. “They have to tap the small towns, they have to tap the villages,” he says, and that means mobile-friendly subscriptions.

But customers in those places, he warns, are living on tight budgets and have limited storage capacity on their phones. They are unlikely to stump for more than one subscription service, and “eventually, only the best will survive”.

Netflix’s grand plans could come undone if regulators get involved. The company will likely have watched with trepidation the recent attempt by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) to allow TV subscribers in India to pay only for the channels which they wish to watch. If translated into the streaming market, it could lead to the emergence of a so-called “super aggregator” – a catch-all platform that would allow customers pay much smaller amounts for specific programmes, rather than for monthly plans.

Judging by its spending, Netflix is certainly determined to be among the survivors.

It has increased its investment in India at a faster rate than any other market, and has 13 new films and nine new original series in the pipeline. The hope is that these titles – a mixture of drama, horror and comedy, made in collaboration with huge Bollywood names such as Shah Rukh Khan – will follow thriller series Sacred Games and Amazon’s cricket soap Inside Edge in attracting big audiences beyond Indian shores.

If successful, Indian hits – which are cheaper to produce than those made in the US – could help Netflix in its battle to stand up to streaming entrants such as Disney, Apple and HBO back home.

Yet those sharks, Rohit Khilnani says, could be circling in India too.

With its family-friendly collections, he predicts, Disney would be a huge hit in the world’s second-most populous country, and could even eclipse Netflix.

“The library that Disney offers,” he says, “I don’t think anyone in the world can beat that”.