WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

GLOBAL RECESSION BLUES?

Shiran Fernando evaluates how global risks could shape Sri Lanka’s economic outlook

The drumbeats of a global economic recession are gradually becoming more insistent. Moody’s Analytics Chief Economist Mark Zandi reportedly stated that there are “awfully high” risks of a global recession materialising in the next 12 to 18 months.

And at its meeting in October, the IMF cut global growth forecasts to their lowest level since the global financial crisis of a decade ago.

This is driven by the impact of the ongoing US-China trade war, uncertainty regarding Brexit and a slowdown in emerging markets. According to Zandi, it would require many of these variables to “stick to script” in the same period to avoid a global recession.

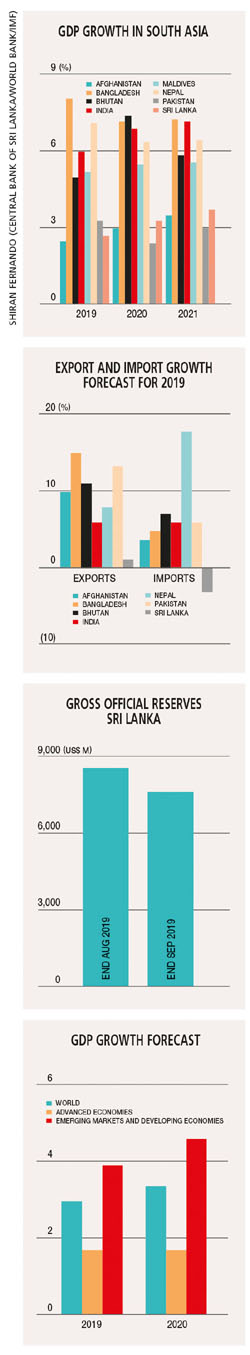

SOUTH ASIAN IMPACT Against this backdrop of an easing of growth, South Asia has also lost steam and is no longer expected to be the fastest growing region in the world. In its latest update, the World Bank cut its growth forecast for the region by 1.1 percent to 5.9 percent. A drop in domestic demand in India is a key reason for the slowdown. This is visible in the contraction of imports.

In the meantime, Pakistan and Sri Lanka have witnessed notable declines – in the first eight months of this year, Sri Lanka’s imports fell by 15 percent.

According to the World Bank, the slowdown in South Asia resonates with similar periods in 2008 and 2012. However, it is optimistic that growth in the region can rebound on the back of improvements in investment and private consumption. As such, growth is expected to be 6.3 percent in 2020.

LOCAL IMPLICATIONS Sri Lanka is likely to post the second weakest growth in South Asia this year. This outcome is set to improve marginally in 2020, as its growth supersedes that of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The country is far short of projected growth rates for Bangladesh, which are expected to be 7.2 percent and 6.9 percent in 2019 and 2020 respectively. Growth in Bangladesh is supported by strong macroeconomic fundamentals, political stability and robust public investments. These factors are lacking or weak in the Sri Lankan context.

Sri Lanka’s macroeconomic variables are stable at best but sensitive to global and local stress. Political stability, which has been deeply desired in recent years, is expected to materialise once a parliamentary election is held in the first half of next year.

The nation has had to scale back public investment (i.e. what the government can provide through its annual financial plan) to keep the budget deficit in check. There is a lack of fiscal space to manoeuvre this to spur higher public investment. Therefore, an enabling environment is required for private investment to thrive.

FINANCIAL MARKETS Sri Lanka has to manage its debt burden carefully in the next few years. The country’s high debt as a share of GDP has been in the spotlight for some time. But much like it is with a business or company, it’s the management of cash flow that matters.

This has been achieved somewhat diligently by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, enabling the state to honour its refinancing commitments. The Central Bank has been compelled to time its entry into international capital markets and ensure it raises the right amount of debt at competitive rates.

These inflows prop up reserves in the short term, which reduces as debt outflows come into play. For instance, Sri Lanka’s reserves amounted to US$ 8.5 billion at the end of August but fell to 7.6 billion dollars by 30 September.

The decline of US$ 900 million over a month was set against the backdrop of outflows of about 830 million dollars in September. This highlights the ebb and flow of reserves. What’s more, the Central Bank requires favourable global financial markets for its reserves management to be successful.

INTEREST RATES Global financial markets would react to policy moves by central banks such as the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and People’s Bank of China. So far, they have eased interest rates to support growth. However, this is not sustainable in the long run as resources on this front are limited.

If the Fed continues to signal that it will cut rates, this might prove to be favourable for emerging markets. And if interest rates decline on the back of expectations of further weakness in growth, this may cause global investors to turn to less risky assets.

But the gloomy global outlook does have the potential to turn around. If the trade war deescalates, a resolution to Brexit transpires sooner rather than later and governments around the world take progressive steps to address structural changes in the economy, there’s hope that global growth will be back on track.

For Sri Lanka next year, it will be about keeping an eye on global developments while the domestic political economy plays out.