BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

The ‘ethnic conflict’ in Sri Lanka had another side to it: writers in uniform whose existence was known only by a name in some instances have come forward to record their memoirs.

General Kamal Gunaratne, now Secretary of Defence, led the way with his classic Road to Nandikadal. The book established records and remains a bestseller as he wrote not only about victories but also mistakes made – and what really went on in the army.

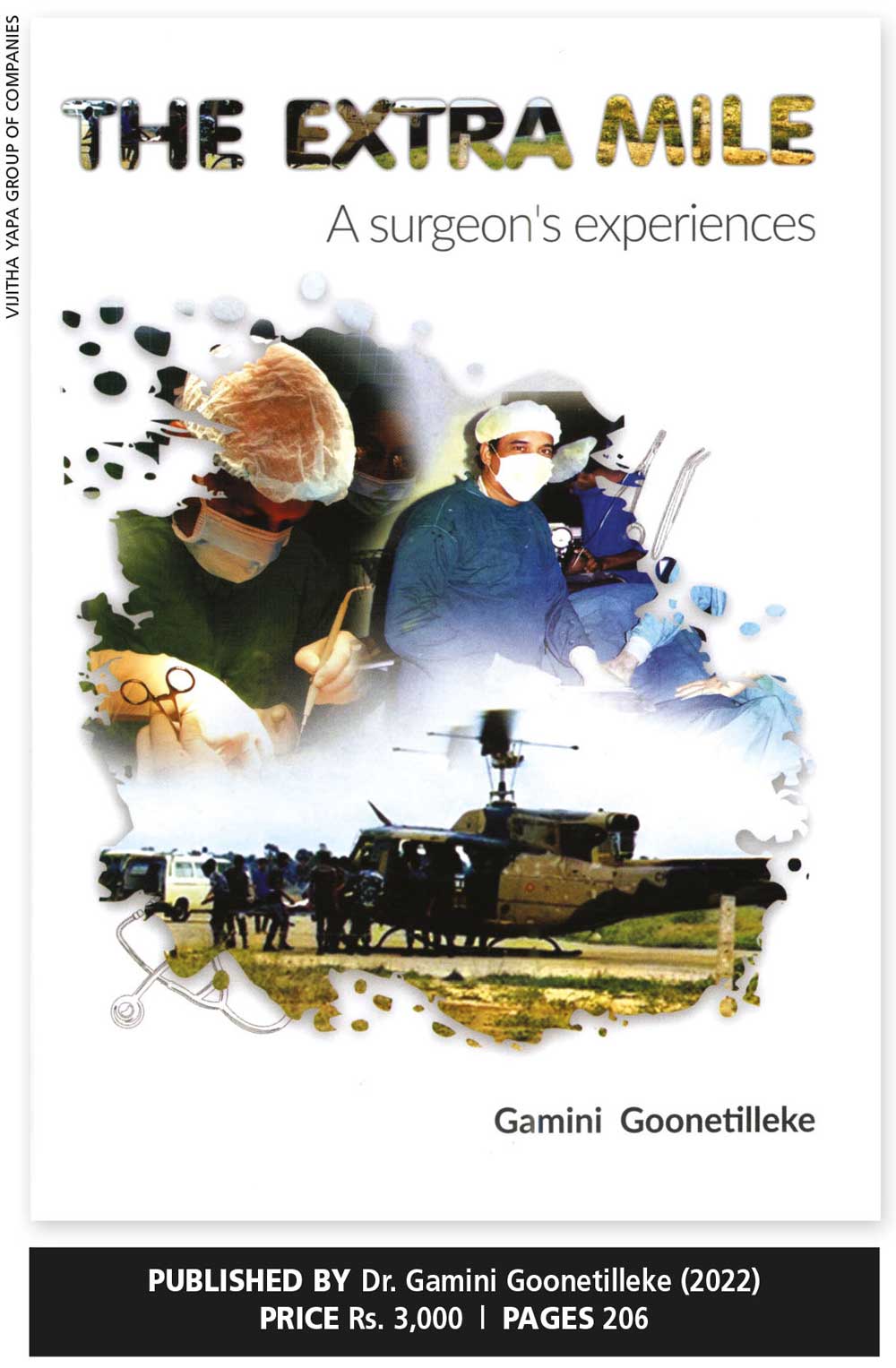

However, the book authored by Dr. Gamini Goonetilleke explains how he didn’t fight the same war with guns but syringes and a surgeon’s skills instead.

It’s a remarkable story of a man who fought against disease and for the lives of those ravaged by battlefield wounds. To him, it was not the army combatting terrorists but a battle to cure and keep safe those who suffered.

An interesting occasion was when he went to the Jaffna Hospital in November 1994, which was in an area controlled by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The LTTE gave him permission to visit Jaffna as an examiner in the MBBS final examination.

Goonetilleke was the first Sinhalese doctor from the south to enter Jaffna after the start of the war. A female medical student who sat the examination was the wife of a leading LTTE member. Those who were qualified were awarded the MBBS (Jaffna) degree.

One of the highlights of his visit was to meet a Sinhalese fisherman from Chilaw who was a patient at the Jaffna Hospital together with his friend Ranjan.

Somaratne was undergoing treatment for kidney stones while Ranjan was being treated for injuries sustained to the face. They pleaded with him to try and get them released, and his appeals to the LTTE on their behalf were successful.

The author says kerosene was the only fuel available for purchase by civilians and it was distributed to them through cooperative stores. The regulated price of a litre of kerosene was Rs. 18 but they had to pay between 350-500 rupees for a bottle. People in Jaffna depended on kerosene to light their lamps at night.

Today, we are queuing up for fuel, gas, milk and more. How many of us remember that the people of the north suffered for decades during the protracted war?

He describes how doctors including a few consultants at the Jaffna Hospital came to work on their pedal cycles. The Government Medical Officers’ Association (GMOA), which has often resorted to strike action demanding new vehicles, should be reminded of the author’s experiences in Jaffna.

“No one complained or asked for official vehicles or ambulances to reach the hospital,” he recalls.

The author discusses how people in Jaffna had to modify the few cars that were available to start on petrol and then run on kerosene. Interestingly, he was the only guest in the 30 room Subhas Hotel. His service was unique as he was treating people in the south, and also had an opportunity to treat LTTE cadre who were injured and warded at the Jaffna Hospital.

Goonetilleke began working at the Polonnaruwa Hospital as a consultant surgeon. It was here that he was exposed to treating war injuries for the first time in his surgical career. The doctor says he had to go the extra mile.... even venturing out to the battlefront to relieve the suffering of those injured.

He is proud to record that our kings of old had paid attention to the health of their people, and reveals that surgical instruments including probes, scalpels, scissors, lancets and medicinal troughs had been discovered at excavations.

His experience in Polonnaruwa helped him; and now, he writes about the challenges faced wherein it was a case of learning on the job, and educating himself and others on his team about the management of war injuries.

There were no books on wartime surgery or reference material on the subject in the library in Polonnaruwa; and nor were there internet facilities at the time.

He has many photographs of the injuries endured by our soldiers to whom he attended. The sight of men with their intestines hanging out reminds one of recent scenes in Rambukkana where the police – who had orders to shoot below the knee – shot people in the stomach instead.

This is a book that moves one to tears. I am reminded of a visit to a military cemetery in Kohima, Nagaland, where there’s a board that says: ‘When you go home, tell them of us and say – for your tomorrow, we gave our today.’

The war is over and new battle lines are being drawn. But Dr. Gamini Goonetilleke’s book urges us to never forget the people who sacrificed their lives, limbs, eyes and future for us – especially those young soldiers who hailed from their wattle and daub huts in the remote villages of Sri Lanka.