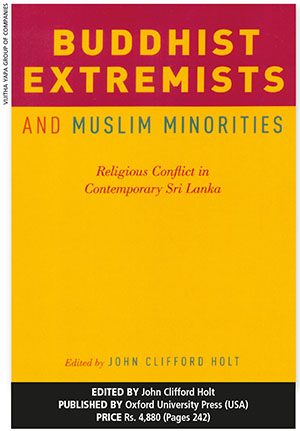

BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

A distinguished breed, serendipity or discovery by accident seems to be the scholar’s guideline. Finding subjects to write about is a continuous dilemma and their antennae continue to search the world for new avenues.

A distinguished breed, serendipity or discovery by accident seems to be the scholar’s guideline. Finding subjects to write about is a continuous dilemma and their antennae continue to search the world for new avenues.

With Islamaphobia gripping many Western nations and the issues facing the Rohingya by the authorities in Myanmar being old news, Sri Lanka’s Muslim minority and the budding Buddhist militancy – by some men in saffron robes – is a new subject on which to write.

Why these men in robes don’t make an effort to take on their own clergymen and clean up their institution to rid it of unsavoury elements is a mystery to me. Perhaps it should be the subject of another book!

The editor of this publication John Clifford Holt is a professor of the Humanities in Religion and Asian Studies at Bowdoin College in the US, and the author of more than a dozen books on the religious cultures of Asia. He provides a lengthy introduction on the history of the Muslims in Sri Lanka who were persecuted by the Portuguese because they were monopolising the spice trade. When they appealed to the king of Kandy, he permitted them to settle in areas within his realm.

What Holt has not said is that some of the Muslims even adopted ‘Ge’ names of the Sinhalese and added these to their lineage although he says some married Sinhalese women. He also doesn’t explain why Muslims whose mother tongue is Tamil continued to live in Sinhalese-dominated areas and perfected the art of Sinhala speech.

The anti-Muslim riots of 1915 began in the aftermath of a Supreme Court decision that upheld the rights of the Gampola Muslims who objected to the perahera passing their new mosque. This created a major controversy and a number of national leaders were arrested. But the editor points out that just before the riots, Anagarika Dharmapala had written that “the Mohammedans, an alien people… by Shylockian method, became prosperous like the Jews.”

Holt adds: “This kind of animosity with its real roots due to the competition in the economy was the main reason” for the anti-Muslim riots. He says the emergence of the Jatika Chintanaya in the late 1970s was a sophisticated version of Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalist ideology, which was much like the Hindutva in India and Talibanist Islamism in the Muslim world.

He believes that “the development of religious and ethnic consciousness has led the Muslims to seek a separate cultural identity based on the fundamentals of their religion Islam to differentiate themselves from other Sri Lankan ethnic groups.”

The most extensive and serious anti-Muslim violence since independence in 1948 broke out in June 2014 in Aluthgama, reportedly instigated by the Bodu Bala Sena (BBS) at an anti-Muslim rally. At the time of writing, BBS firebrand – its General Secretary – Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara Thera continues to be in hiding despite being sought by the police on a contempt of court charge.

Professor Holt points out that a category of political Islam that began in the Middle East has emerged in Sri Lanka as an overarching political force. He believes that the de-ethnicisation of Sri Lankan society will be a major challenge for the country.

The book draws attention to the schisms that occurred in the Kandyan kingdom when elite monks pressurised King Kirti Sri Rajasinha to issue a decree that only people of the Govigama caste could be ordained as priests. As a result, those from the Salagama caste who wanted to be ordained travelled to what was then Burma to receive a higher ordination. Upon their return, they established the Amarapura Nikaya.

He compares this to the rise of the Jathika Hela Urumaya (JHU), and how it contested elections to enter parliament and worked with governments to transform them from within.

Although the JHU isn’t affiliated to any specific nikaya, the case of Ven. Omalpe Sobitha’s reaction to the Mahanayake of the Malwatta Chapter asking him to stop his fast unto death in 2005 is cited. The monk had requested the mahanayake to ask the president to stop destroying the country.

The book says that the BBS – like the elite monks of the Kandyan kingdom and those of the early JHU – have invented new methods “to engage in sociopolitically powerful displays of discourse on virtuous governmentality.”

But there’s an interesting question from Holt: “For whom do Gnanasara and the BBS speak? Why have they perceived Muslims to be the new threat against Buddhism at this time, much like the Kandyans saw the British and the JHU saw evangelical Christians in their day?”

Contributions by a Buddhist monk and a Muslim in the book would have introduced different and interesting perspectives.