WORLD TRADE

GLOBALISATION IN RETREAT

Samantha Amerasinghe notes how the pandemic is catapulting de-globalisation

COVID-19 is driving the world economy away from global economic integration. However, it is important to recognise that several factors were already at play against globalisation before the pandemic hit.

These include the flattening growth of global value chains (the spread of supply networks across countries), the stalled global reform agenda, an inward looking China from a policy standpoint and under President Donald Trump, the US’ ‘America First’ policy with a strong shift away from trade liberalisation toward greater protectionism.

The pandemic has simply added further momentum to the de-globalisation trend.

Consequently, the WTO has forecast that world trade will plummet by between 13 and 32 percent this year, much more than the expected fall in global GDP. While trade has tended to grow more rapidly than world output in past decades, that is no longer the case.

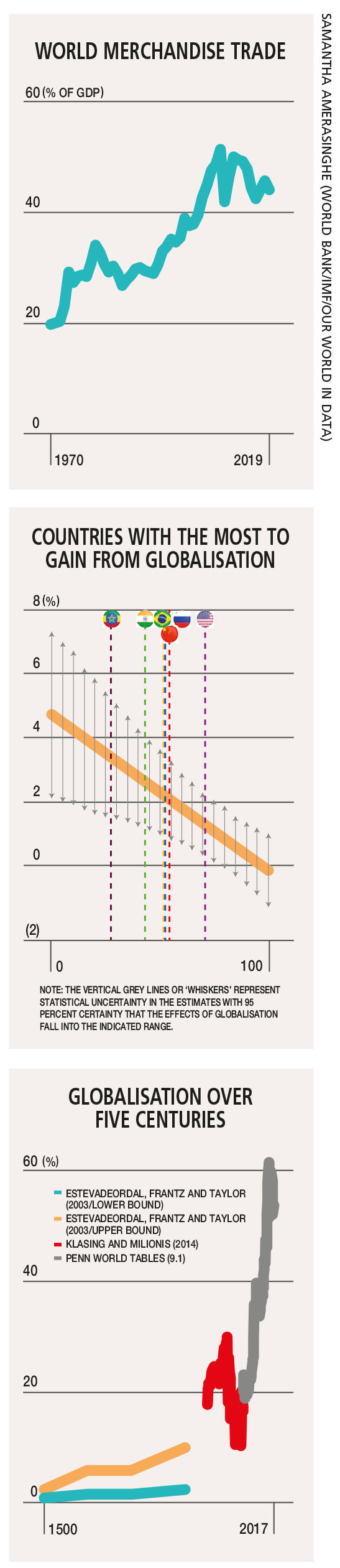

Instead, trade growth has been abnormally weak in recent years. World trade volumes fell in 2019 although the global economy grew steadily.

Modern globalisation – consisting of cross border trade flows, investment, data, ideas and technology, not to mention people – has evolved through five eras.

The fourth era of globalisation appears to have peaked in 2007 with global cross border capital flows amounting to approximately US$ 11.8 trillion.

However, the financial crisis that followed contributed to a reversal of this trend with markets displaying the first signs of ‘de-globalisation’ as a result. World trade bounced back in 2010 from the sharp blow in 2009 but has faltered ever since.

Experts argue that we are now in a fifth historical period of globalisation, occasionally called ‘slowbalisation.’ The retreat began with Trump’s victory at the 2016 US presidential election, which led to tariff wars between the United States and China.

Since World War II, the US has been a major architect of globalisation, multilateralism and the ‘rules-based global order.’ It has played a central role in defining and constructing the existing international economic order and its political institutions.

US initiated trade agreements have been central examples of this. In the Trump era, the US reversed course. The Trump administration viewed global trade as a zero-sum game. It rejected multilateral deals under negotiation and threatened to pull out of existing arrangements, reshaping the nature of globalisation.

The world economy is at a critical inflection point with growing fears about dependence on others. In an era where alliances are uncertain and international cooperation is absent (compounded by a failure of leadership in the US), policy makers and business leaders are asking whether they should curtail their economic interdependence.

For many countries, de-globalisation is likely to equate to reducing dependence on China. However, China’s dominance of world trade is unlikely to be challenged in the near future.

In fact, China’s growing importance as a source of foreign direct investment (FDI) for other emerging markets (e.g. through the Belt and Road Initiative) is also likely to help maintain its position as a mega-trader.

Additionally, while the shift to regional supply chains is becoming clearer, factory relocation tends to be a multi-year project involving long planning times and massive investment; the present macro backdrop is probably not conducive to making such commitments.

China is one of the main winners from globalisation but that doesn’t necessarily mean it will be the greatest loser from de-globalisation.

In a recent survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, of more than 200 respondents that own or outsource manufacturing operations in China, 70.6 percent said they do not intend to shift production to the US as Trump had hoped his tariffs would make them.

Interestingly, 28 percent of those polled in Singapore said they are setting up or using alternative supply chains to reduce their dependence on China. Among those opting to move capacity overseas, Asia remains the preferred destination with countries such as Vietnam, Cambodia, Bangladesh and Thailand the most favoured locations.

This suggests that countries considering relocating from China are mostly low end producers in sectors such as textiles and garments, consumer discretionary, and electronics packaging and assembly.

Even the US, with its diverse economy, world leading technology and strong natural resource base could suffer a major decline in real GDP as a result of de-globalisation. For smaller economies and developing countries that are unable to reach critical mass in many sectors and often lack natural resources, a breakdown in trade would reverse many decades of growth.

One factor is certain: the pandemic has changed the way countries think about economic integration. It has changed the nature of globalisation with which we have lived for the past 40 years.

This will not reverse with a change in the US administration although President-elect Joe Biden would seek to restore a more multilateral approach to US foreign policy with diplomatic engagement with the world likely increasing significantly.

However, a decline in the US’ relative power and accelerating de-globalisation would limit his ability to reestablish America’s past influence over the world.