WASTE MANAGEMENT

THE GARBAGE MENACE

Gloria Spittel writes that a change of lifestyle is needed to curtail waste

In June, the fire on the MV X-Press Pearl resulted in Sri Lanka’s coastline being polluted with nurdles (pellets) to varying degrees. These pellets will degrade over time into extremely tiny particles, which smaller animals such as plankton will consume mistaking it for food.

This pollution will play out for years to come with devastating effects on both human and marine life.

This pollution will play out for years to come with devastating effects on both human and marine life.

Garbage comes in many forms and sizes; it includes municipal solid waste such as what’s collected from residential, commercial and institutional sources, and constitutes organic waste, plastic, electronic, paper, metal, glass etc.

Industrial waste has historically been linked to environmental disasters when proper disposal methods weren’t implemented, or ignored or flagrantly disregarded.

But the line between environmental and municipal waste is murky when industrial policies cause disruption to and destruction of ecosystems that sustain economies, which are based on agriculture and food.

This results in produce that’s unfit for consumption and ends up as waste that is then counted as municipal waste in locations that rely on a state waste collection system rather than industrial waste disposal.

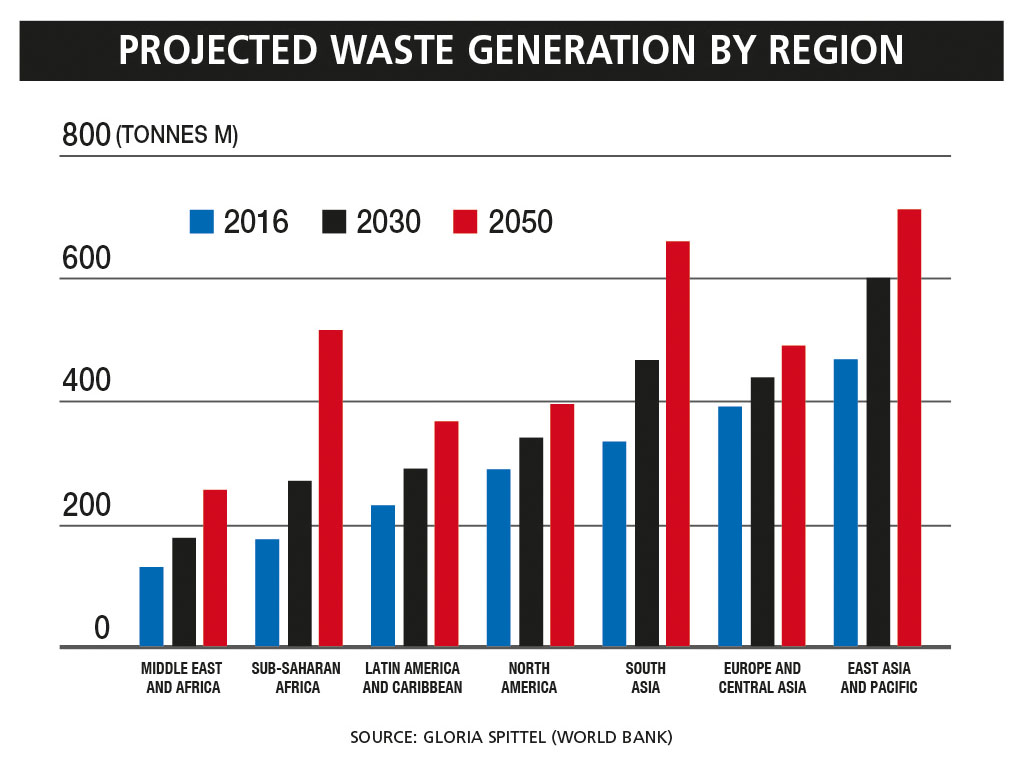

Often overshadowed by plastic, electronic, and other nonbiodegradable and often hazardous waste is food waste. According to a 2016 World Bank study (What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050), over 40 percent of global waste comprises food and green waste.

It also reported a correlation between the composition of waste and income levels, suggesting that higher income countries produce more dry waste (including recyclable materials) than nations with lower income levels (they produce more organic waste).

In fact, other than Europe, Central Asia and North America, all other habited regions of the world generate around 50 percent of organic waste.

One reason for food waste in lower income countries could be due to systemic issues that don’t prevent food loss along supply chains, produce that’s vulnerable to extreme, and unpredictable weather fluctuations owing to climate change and other technical and operational limitations.

Food waste has damning repercussions on a nation’s food security, environmental sustainability and economy with myriad spillover effects, especially with regard to the health and wellbeing of the populace. The study estimates that 30 percent of all food produced globally ends up as waste.

The tying of income levels to waste type generation is less curious than initially thought when consumerism is factored in. Increasing disposable income is said to lead to a higher quality of life – and in higher income countries, this mainly translates into a consumerist lifestyle.

In this scenario, food waste is controlled through lifestyle habits, and better supply and production systems that seek to eliminate waste.

Surely, not all waste is equal; nor is all waste equally bad?

The latter is more reflective of the world we live in because while organic waste decomposes especially in landfills, it leads to the degradation of soil and release of harmful greenhouse gases that contribute to worsening climate change.

On the other hand, the same is true of dry waste or waste that’s produced in higher income countries with claims of recyclability when in fact, approximately only nine percent of plastic waste (of the 6.3 billion metric tonnes generated) has been recycled.

Scratch a little deeper below the surface of recyclable plastics and waste, and it becomes a diplomatic topic – a good old geopolitical flashpoint.

Countries like the US, the UK, Germany, Canada and Australia sent large shipments of waste commonly thought of as recyclable to nations such as China, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines.

Countries like the US, the UK, Germany, Canada and Australia sent large shipments of waste commonly thought of as recyclable to nations such as China, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines.

In 2017, for a variety of reasons including wrongly labelling waste as recyclable and dispatching waste that was not recyclable, China imposed a ban on importing waste. This was either in response to the quality of the waste sent across or as a response to former US President Donald Trump’s trade policies on goods and services manufactured in China.

Whatever the reason, the ban led to an implosion of garbage in countries that had previously exported their waste. A coping mechanism that included the burning of nonbiodegradable goods for energy released more pollutants into the environment.

Other countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines too have in the recent past sent back or stopped accepting imported waste. In 2019, Sri Lanka also sent hundreds of tonnes of garbage back to the UK.

So what can be done about the overabundance of garbage?

The answer lies in changing lifestyles. While any change that reduces waste and single-use consumables is positive, a larger coordinated front is necessary for a recognisable impact. And this needs to include government, private sector and public buy ins, as well as cooperation.

And like most ills that our beleaguered planet is facing, cooperation between world governments would be a step in the right direction… but who is willing to bring those horses to water?

Rich nations will not change their ways.

It is very true that there is a correlation between the composition of waste and income levels. Yes, and that that high income countries produce more dry waste than others. The problem is that this will not change because the developed world is selfish. They want us to change without doing the same. The same is true as to whom to blame for climate change. It is very sad that the United Nations is powerless because of the right to veto held by the richest countries in the world.