THE B3W INITIATIVE

BUILD BACK BETTER WORLD

Samantha Amerasinghe reviews the G7’s alternative to China’s BRI initiative

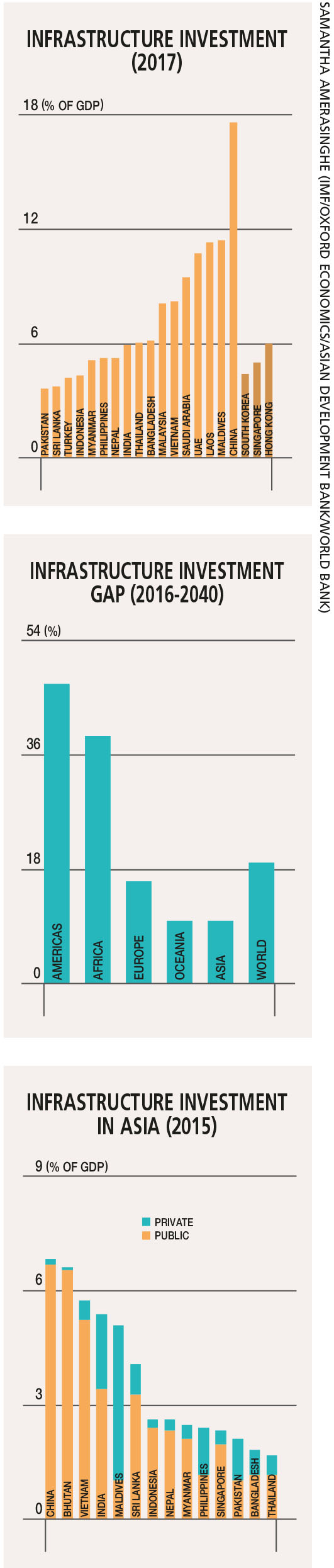

In the June edition, we commented on Asia’s infrastructure deficit – and how infrastructure will be the key to economic recovery in the post-pandemic era. We emphasised that China – through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – has been a major funder of developing country infrastructure, lending US$ 40 billion annually and helping to not only bridge Asia’s large infrastructure funding gap but also reassert its influence as a global powerhouse.

China’s meteoric economic and military rise in the past four decades to become the world’s second largest economy is remarkable.

China’s meteoric economic and military rise in the past four decades to become the world’s second largest economy is remarkable.

In this issue, we discuss one of the main initiatives launched at the recent G7 summit – i.e. Build Back Better World or B3W. President Joe Biden clearly sent a message that ‘America is back,’ stating that the world’s richest democracies can offer an alternative to China’s growing clout.

Nonetheless, critics have argued that while B3W is an ambitious plan, it has come about very late and questions over its funding have raised doubts about whether the initiative is realistic.

So does the B3W initiative stack up to what China’s already well-developed BRI offers?

Since President Xi Jinping launched the initiative in 2013, more than 100 countries have signed agreements with China to cooperate on projects such as railways, ports, highways and other infrastructure, stretching from Asia to Europe and beyond.

According to recent data, more than 2600 projects at a cost of 3.7 trillion dollars were linked to the initiative in mid-2020.

According to recent data, more than 2600 projects at a cost of 3.7 trillion dollars were linked to the initiative in mid-2020.

The B3W project championed by the Biden administration aims to compete with China’s BRI, which has been widely criticised for crippling lower income countries with unmanageable debt, leaving them politically beholden to the superpower.

Through B3W, the G7 and other ‘like-minded partners’ will coordinate in mobilising private sector capital in four focus areas – viz. climate, health and health security, digital technology, and gender equity and equality – with catalytic investments from development finance institutions covering low and middle income countries across the world.

The project aims to offer a more ‘equitable’ way of providing for the needs of developing countries to fill the gaping hole left by the West for so many years – in other words, the failure to offer a positive alternative to the “lack of transparency, poor environmental and labour standards, and coercive approach” of the Chinese government, which has arguably left many countries worse off.

However, big question marks hang over the initiative’s funding. Closing an estimated US$ 40-plus trillion infrastructure gap – which has been exacerbated by the pandemic – between now and 2035 will be a challenge. It is hard to believe that the G7 countries could offer such a sum of money, which is more than their combined GDP last year.

Moreover, the US has seen record high national debt and the Biden administration’s new proposed infrastructure plan to upgrade outdated American infrastructure was recently downsized from the original 2.3 trillion dollars to US$ 1.7 trillion, which still seems unlikely to gain the support of Republicans.

The US stands out as a nation where private investment in infrastructure remains well below optimal levels. Experts say that its infrastructure is dangerously overstretched and lagging behind that of economic competitors – particularly China.

Most of the country’s major infrastructure systems were designed in the 1960s. Since then, the population has doubled and many systems are at breaking point, close to reaching the end of their lifespans.

A 2017 American Society of Civil Engineers report found that the country’s infrastructure averaged a ‘D+,’ meaning that conditions were “mostly below standard,” exhibiting “significant deterioration” with a “strong risk of failure.”

The report estimated that an “infrastructure gap” of more than two trillion dollars must be closed by 2025; and if not addressed, would result in almost US$ 4 trillion of GDP being forgone.

The United States generally lags behind its peers in the developed world. According to the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Competitiveness Report, it ranked 13th across a broad measure of infrastructure quality in 2019 (down from fifth place in 2002), placing it behind countries such as France, Germany, Japan, Spain, the UAE and the UK.

A broken financing system – or simply put, funding – has been the main issue for the US compared to its peers.

Infrastructure projects usually demand huge investments while having long horizons for returns. There are likely to be significant obstacles in mobilising private sector capital to join any projects with long payback periods while the climate and other areas mentioned in the B3W proposal aren’t in line with the current development demands of the less developed countries.

Not to mention the distinct technological gap between China and most Western countries when it comes to infrastructure construction. China has been a leading player in the infrastructure sector with distinct advantages in related technology, talent, experience and management, as well as capital.

With the US having to grapple with challenging infrastructure gaps and funding issues of its own at home, it remains to be seen if the B3W initiative will take flight and offer a competitive alternative to the BRI.

Or does the B3W simply underscore Biden’s push to reestablish the United States as a hegemon in the world order?

Time will tell…

Leave a comment