UK-EU TRADE IMPASSE

THE BREXIT CLOCK IS TICKING!

Samantha Amerasinghe evaluates the countdown to the transition deadline

With the UK now eight months into its Brexit transition period with the EU, the clock is ticking. Brexit represents the most important constitutional shake-up the UK has known since it joined the six nation EEC in 1973.

In June 2016, the UK voted to leave the EU (by a majority 52%), following decades of increasing hostility towards the ‘European project,’ reinforced in recent years by a rise in nationalist sentiment and populism.

Other factors such as austerity and frustration with traditional politics have also been cited as reasons for Brexit.

The UK left the EU on 31 January and is no longer part of the bloc’s institutions. Moreover, the transition period ends on 31 December, by which time both sides aim to strike a deal on trade and the future UK-EU relationship.

Negotiations over the UK’s new relationship with the EU are at an impasse. While both sides desire an FTA and close alignment, what Prime Minister Boris Johnson really wants is the UK’s independence from Brussels.

Both sides have expressed frustration at the lack of progress towards a deal, following intensified talks at the time of writing.

Michel Barnier, the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator, has blamed the UK for dragging its feet and backtracking on commitments while his British counterpart David Frost has been frustrated by the EU’s ideological approach. With less than four months to go, serious divergences between the two sides remain.

Meeting the tight transition deadline was going to be a huge challenge even before the fierce onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite a stalemate at the talks, the UK has ruled out any extension to the transition period. The burning question is whether the UK and EU will reach a formal deal by the end of this year.

It is wishful thinking to believe that a comprehensive free trade deal will be negotiated in such quick time. Brussels has not yet decided whether it is ready to accept Johnson’s offer of a Canada style FTA. A report from a UK based think tank ‘UK in a Changing Europe’ says an extensive trade deal could take years to negotiate.

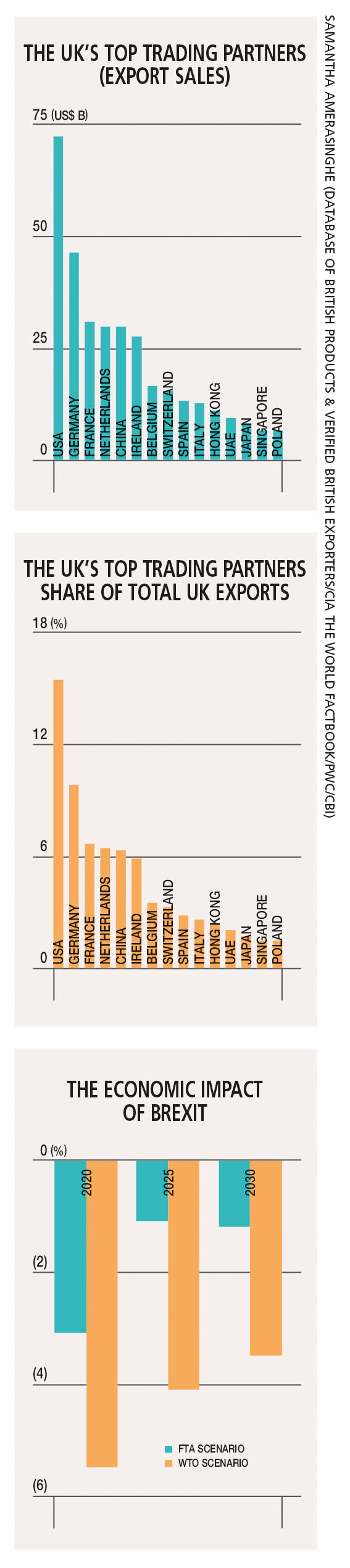

EU-Canada trade deal negotiations began in 2009 and all EU states are yet to ratify it. UK-EU trade is on a much larger scale (volumes are almost six times higher) than Canada’s trade with the EU. Furthermore, almost half of the UK’s international trade is with the EU and it is a significant player in the financial services industry in particular.

Trade experts believe that a deal is possible but failure to reach an agreement would lead to a new cliff edge scenario – a WTO Brexit, which will subject the UK to tariffs on trade, and new ways of maintaining law enforcement and security cooperation.

This outcome seems increasingly unlikely as discussions have been constructive, and both sides have shown pragmatism and a willingness to move on difficult areas. However, according to Barnier, the entire trade deal hinges on securing access to Britain’s fishing grounds.

Trade negotiations are usually win-win scenarios but have become a zero-sum game for both the UK and EU. Regulations rather than trade have become the main objective of negotiations with the UK seeking maximum regulatory independence and the EU wanting to prevent it on grounds of competition.

Clearly, neither side can declare victory as a deal that satisfies both objectives is nonexistent. While a level playing field seems to be the main sticking point, the EU’s other preconditions for negotiating a trade deal, fisheries and the role of the European Court of Justice will also

define what the future economic partnership between the EU and UK looks like.

The UK’s negotiating mandate asks for a liberalised market for trade in goods with no tariffs, fees, charges or quantitative restrictions on trade in manufactured or agricultural products; and competition and subsidies to not be subject to the final agreement’s dispute resolution mechanism.

It also seeks a separate agreement on fisheries that would enable annual negotiations on access to each other’s waters including permissible catch and shares – the EU wants fishing to be considered as part of the overall agreement; an agreement on equivalence on financial services; and no participation in the European arrest warrant but an extradition agreement like the EU has with Iceland and Norway.

And while the EU wants one overarching agreement underpinned by a common dispute settlement system, the UK desires a series of Swiss style mini-deals. The EU is concerned that having multiple deals will make ratification more difficult with potentially 27 EU member states wanting a say.

Indeed, the formidable challenge of securing a trade deal during the transition period looks daunting but both the UK and EU are cognisant that a deal in some shape or form (by October at the latest, to leave sufficient time to ratify it) might be the tonic they urgently need to shore up the bleak economic outlook, which has been further exacerbated by COVID-19.