THE EU TODAY

THE UNION ON A CLIFF EDGE

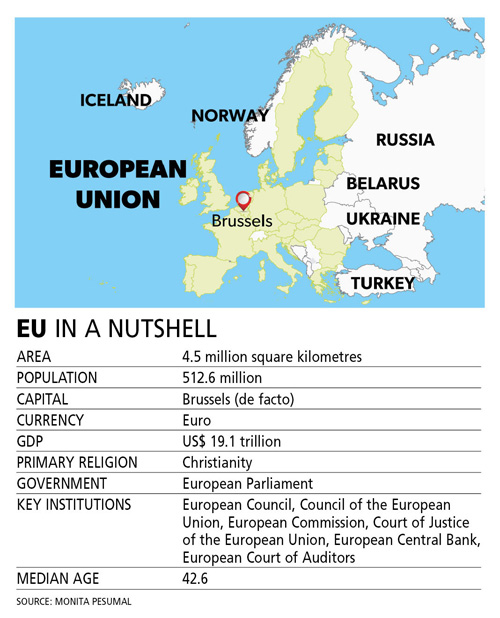

Monita Pesumal assesses the political and economic landscape of the EU in the wake of Brexit

Formed in 1957 as the European Economic Community (EEC) and including six countries (i.e. Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and erstwhile West Germany), the initial aim of this organisation was to remove trade barriers and form a common market.

Today, with 28 member states and its own parliament, the objectives of the EU are to establish European citizenship; ensure freedom, justice and security; and foster economic and social progress – in a nutshell, to assert Europe’s role in the world.

Members of the European Union share a common currency – the euro (EUR) – which came into being in 2002. EU countries also hold their red passports in common, and citizens have the added advantage of being able to live and work in any member country subject to certain limits.

And here’s a little fun fact: the EU has 24 official languages and European parliament debates are translated into all of them.

In terms of GDP, the economic output of the unified monetary body is greater than that of the American economy. The European Union’s GDP in 2018 was estimated to be EUR 18.8 trillion, representing 22 percent of the global economy. And over 64 percent of EU countries’ trade is within the bloc. Along with the US and China, the EU is one of the most dominant players in international trade.

You could say the going was good until 23 June 2016 when all hell broke loose and the UK voted to leave the European Union. Some 17.4 million Britons decided that the benefits of belonging to the bloc no longer outweighed the cost of free movement and trade.

On 29 March 2017, British Prime Minister Theresa May triggered Article 50, the official withdrawal notification from the EU. It provided the UK and the EU two years to negotiate an agreement. And due to a lack of consensus in the British parliament, the European Union has agreed to extend the ‘British exit’ deadline until 31 October this year.

But what does Brexit really mean for the EU?

Well for starters, a ‘no deal Brexit’ implies that the UK would have failed to settle on a withdrawal agreement. This will mean that there would be no transition period after Britain leaves and EU laws would immediately cease to apply to the UK. Britain’s relationship with the EU would be governed not by common rules and regulations that have accumulated over four decades but rather, by international public law.

In the UK, food prices could rise due to global tariffs set by the WTO. And any price increases resulting from tariffs are likely to be absorbed by consumers.

But it is important to note that for some items such as meat, dairy and tobacco products, tariffs exceed 15 percent. Customs inspections could cost businesses billions of pounds. Everything from mobile phone roaming charges and passport control, to water and electricity supply, would be vulnerable to change.

Furthermore, there would be no specific arrangement on the future rights of EU citizens in the UK and vice versa. In addition, border checks would have to be reimposed, thereby curtailing free movement. And transportation by road, rail, sea and air between the UK and the EU would be severely affected.

Among the serious concerns are the impact of Brexit on future trade, agriculture, fisheries, citizens returning from the UK and cuts to the European Union budget post-Brexit. Member states that are closest to Britain – such as Belgium and the Netherlands – as well as those with high trade volumes (including Germany and France) stand to lose more from the economic impact of Brexit.

Meanwhile, European Union countries that rely on foreign workers to remit money to their homelands could also be affected. Britain is the third largest remitter in the EU and in 2017, migrants from the bloc sent home approximately US$ 9 billion.

There are also concerns about the port of Calais. If the UK leaves the single market and customs union, the police and customs authorities will have to treat the kingdom like they do any other country – i.e. by applying the common customs tariff to goods originating in the UK.

A second and more serious issue pertaining to Calais is migration since it’s the point from which many migrants attempt to reach the UK. The eventual Brexit settlement will be relevant to the management of migration flows between the UK and France, which enables British border police to operate in Calais.

The European Union has demonstrated rock solid unity over the three ‘divorce conundrums’ – viz. citizens’ rights, the Brexit bill and Irish borders. Northern Ireland would remain with the United Kingdom while the Republic of Ireland, with which it shares a border, would continue to be a part of the EU. A ‘no deal Brexit’ would create a customs border between the two and complicate matters further.

However, Brexit does by no means spell the end for the bloc. Currently, countries whose membership is being evaluated include Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Turkey, while Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as Kosovo have also submitted applications for membership.

We have to wait and see what impact Brexit has on the Union.