The Amazon in Brazil is on fire – how bad is it?

Thousands of fires are ravaging the Amazon rainforest in Brazil – the most intense blazes for almost a decade.

Thousands of fires are ravaging the Amazon rainforest in Brazil – the most intense blazes for almost a decade.

The northern states of Roraima, Acre, Rondônia and Amazonas have been particularly badly affected.

However, images purported to be of the fires – including some shared under the hashtag #PrayforAmazonas – have been shown to be decades old or not even in Brazil.

So what’s actually happening and how bad are the fires?

There have been a lot of fires this year

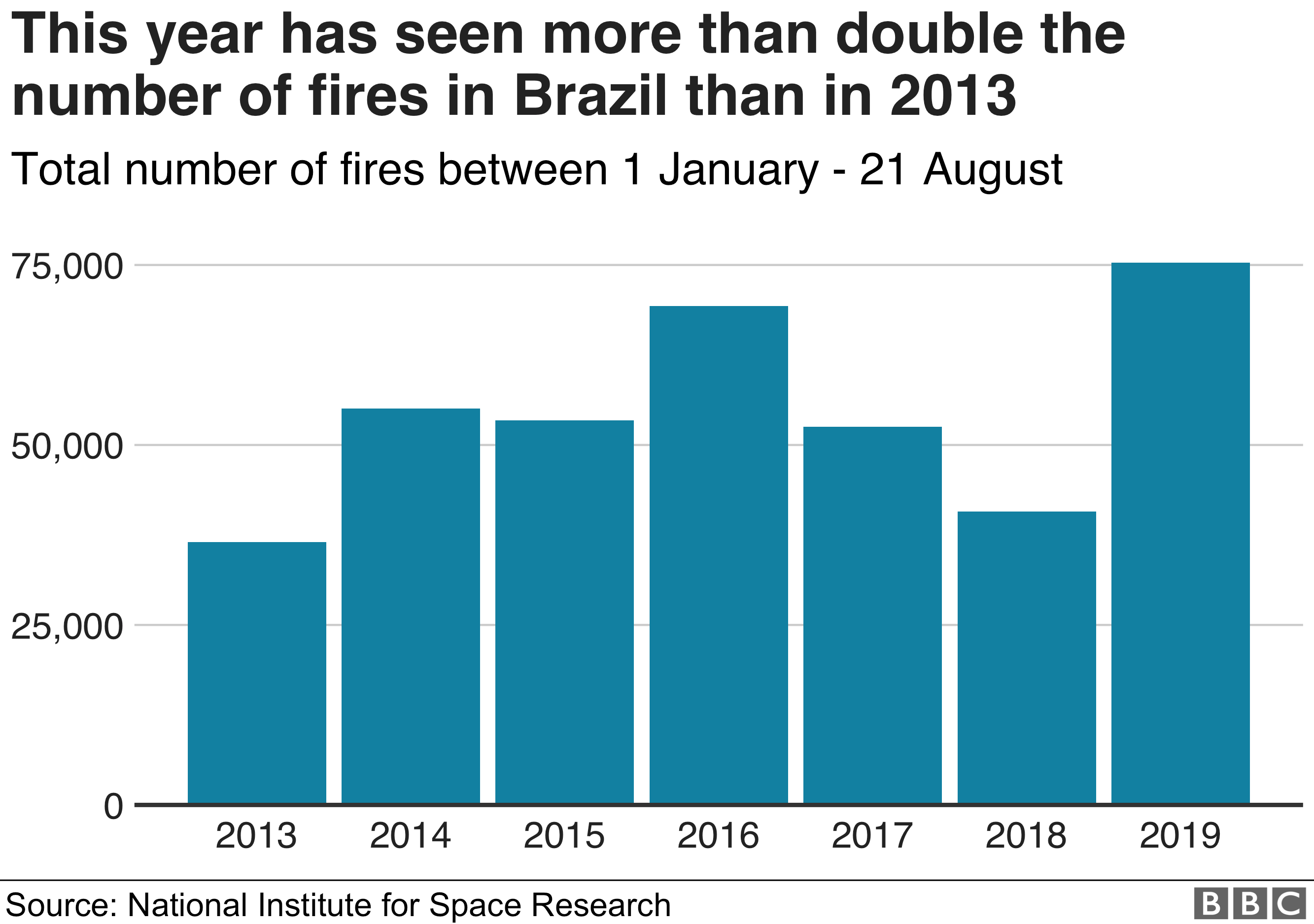

Brazil has seen a record number of fires in 2019, Brazilian space agency data suggests.

The National Institute for Space Research (Inpe) says its satellite data shows an 85% increase on the same period in 2018.

The official figures show more than 75,000 forest fires were recorded in Brazil in the first eight months of the year – the highest number since 2013. That compares with 40,000 in the same period in 2018.

Forest fires are common in the Amazon during the dry season, which runs from July to October. They can be caused by naturally occurring events, such as by lightning strikes, but also by farmers and loggers clearing land for crops or grazing.

Activists say the anti-environment rhetoric of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has encouraged such tree-clearing activities.

In response, Mr Bolsonaro, a long-time climate sceptic, accused non-governmental organisations of starting the fires themselves to damage his government’s image.

He later said the government lacked the resources to fight the flames.

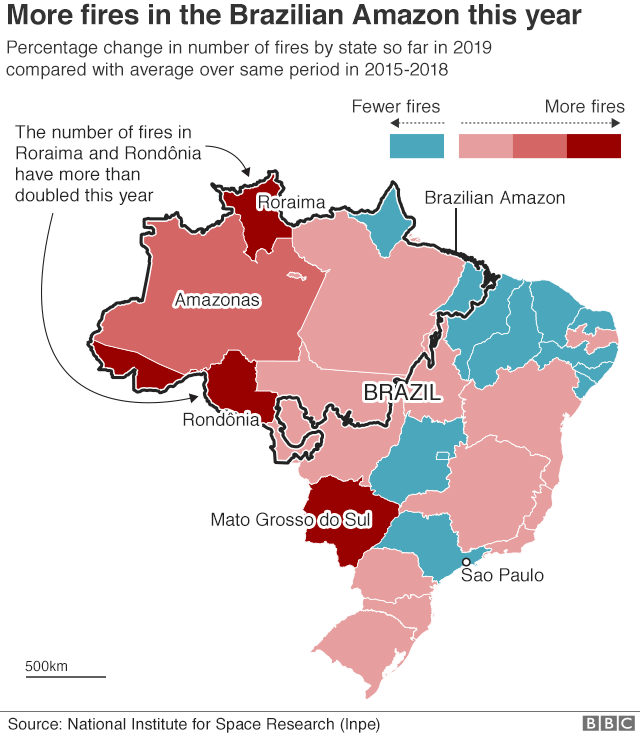

The north of Brazil has been badly affected

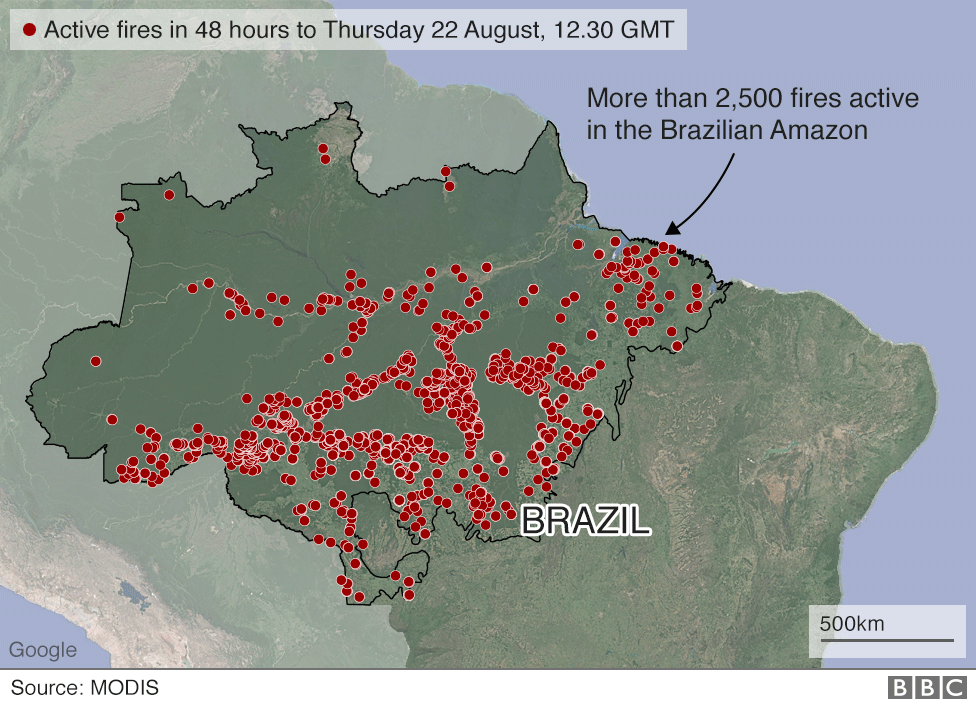

Most of the worst-affected regions are in the north.

Roraima, Acre, Rondônia and Amazonas all saw a large percentage increase in fires when compared with the average across the last four years (2015-2018).

Roraima saw a 141% increase, Acre 138%, Rondônia 115% and Amazonas 81%. Mato Grosso do Sul, further south, saw a 114% increase.

Amazonas, the largest state in Brazil, has declared a state of emergency.

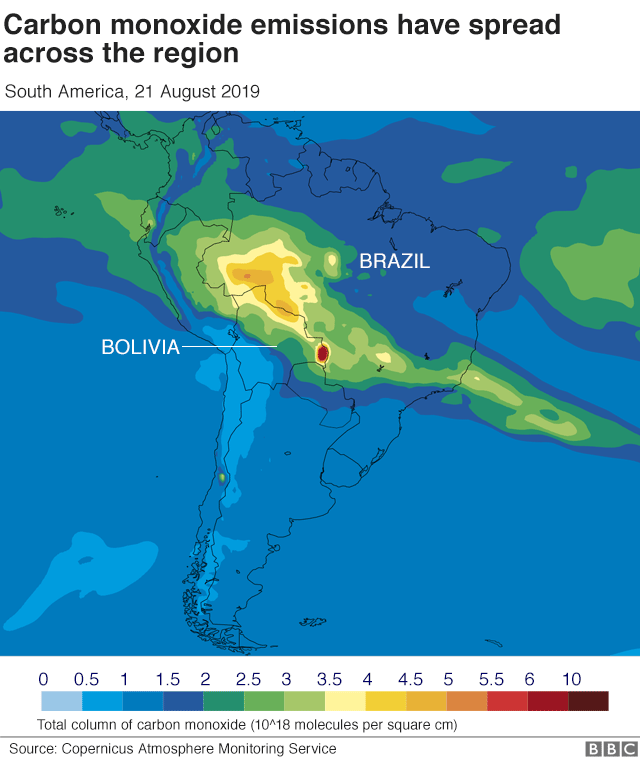

The fires are emitting large amounts of smoke and carbon

Plumes of smoke from the fires have spread across the Amazon region and beyond.

According to the European Union’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (Cams), the smoke has been travelling as far as the Atlantic coast. It has even caused skies to darken in São Paulo – more than 2,000 miles (3,200km) away.

The fires have been releasing a large amount of carbon dioxide, the equivalent of 228 megatonnes so far this year, according to Cams, the highest since 2010.

They are also emitting carbon monoxide – a gas released when wood is burned and does not have much access to oxygen.

Maps from Cams show this carbon monoxide – toxic at high levels – being carried beyond South America’s coastlines.

The Amazon basin – home to about three million species of plants and animals, and one million indigenous people – is crucial to regulating global warming, with its forests absorbing millions of tonnes of carbon emissions every year.

But when trees are cut or burned, the carbon they are storing is released into the atmosphere and the rainforest’s capacity to absorb carbon emissions is reduced.

Other countries have also been affected by fires

A number of other countries in the Amazon basin – an area spanning 7.4m sq km (2.9 sq miles) – have also seen a high number of fires this year.

Venezuela has experienced the second-highest number, with more than 26,000 fires, with Bolivia coming in third, with more than 17,000.

The Bolivian government has hired a fire-fighting airtanker to help extinguish fires in the east of the country. They have so far spread across 2.3 sq miles (6 sq km) of forest and pasture.

Extra emergency workers have also been sent to the region, and sanctuaries are being set up for animals escaping the flames.

By Lucy Rodgers, Nassos Stylianou and Mike Hills