TEA INDUSTRY

GROWTH MODEL

Compiled by Yamini Sequeira

ADDING VALUE TO THE CUPPA

Roshan Rajadurai maps a viable pathway to add value to Sri Lanka’s tea exports

“Sri Lanka’s tea industry continued to function throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent crises – in fact, it may have been the only industry to do so. This homegrown and self-sustaining industry retains 95 percent of its earnings within the country, and trickles down to grassroots communities in small towns and villages,” asserts Roshan Rajadurai.

He affirms that “in spite of all the ad hoc policies imposed on it – such as the sudden ban on inorganic fertiliser and other agrochemicals – the industry has remained resilient, resolute and resourceful.”

CHALLENGES “The ban on chemical fertilisers and agro inputs devastated the agriculture sector; and the consequences are evident: without chemical herbicides to control weeds, 20 percent of the crop was lost,” Rajadurai reveals.

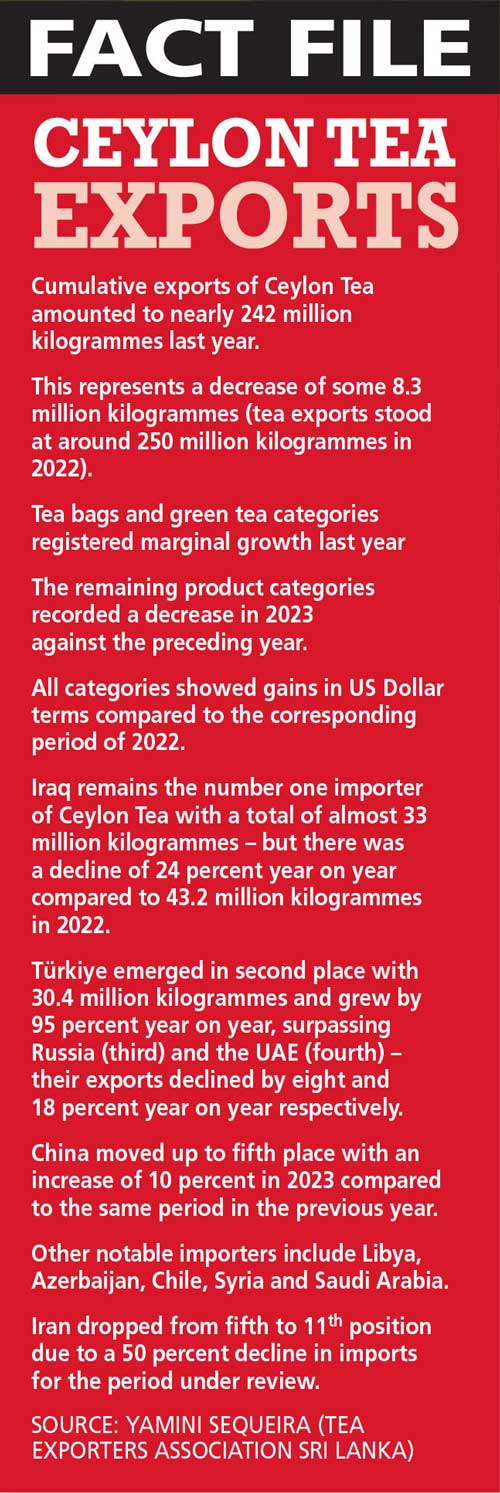

He continues: “Approximately 330 million kilogrammes of tea harvested prior to the glyphosate ban in 2015 declined to 300 million kilogrammes. This quantity shrank to 250 million kilogrammes over eight or nine years as a result of unscientific ad hoc bans on herbicides, fertilisers and agrochemical inputs.”

As a consequence of the tea industry’s decline, local economies connected to the plantations also sustained losses that cannot be quantified, he maintains.

Although fertiliser import protocols have been relaxed, prices remain high and this raises the cost of production substantially. Rajadurai notes that the impact of this is felt most acutely by the tea industry’s smallholder segment because growers lack the necessary cash to invest in fertilisers.

He elaborates: “Tea exporters garnered reasonably good prices last year – i.e. US$ 3.58 for a kilogramme because of the exchange rate. In rupee terms, there was a benefit from higher prices but this was negated by increased electricity, fuel, fertiliser and labour costs. Labour costs alone constitute 70 percent of the cost of production.”

Ceylon Tea continues to fetch higher prices than Kenyan and Indian teas, thanks to its quality. Since the island is unique in the realms of human resources, industrial relations, field management practices, sustainability focus and quality orientation, its teas are easily distinguished from tea produced by other nations.

PRODUCTIVITY Although Sri Lanka’s produce may attract the highest prices at global tea auctions, the industry is plagued by the lowest labour productivity among tea growing countries.

Rajadurai avers: “One of the main reasons for low labour productivity is the archaic attendance-based wage model that persists despite repeated calls for reforms.”

“Plantations that are managed by the corporate sector have adopted a more productivity-based system; this drives higher productivity and motivates workers to earn twice or three times the basic minimum wage,” he discloses.

Rajadurai urges: “It’s high time that unions and other stakeholders accepted this model to ensure sustainability of the tea industry by providing an opportunity for workers to earn more.”

The industry continues to face a scarcity of labour because of out-migration. Only some 115,000 employees are working on tea estates currently, whereas the requirement is for almost 300,000 workers. However, the corporate sector provides custodial care for more than a million people who reside on these plantations.

“We have to reset the tea industry by adopting new and different models to attract workers. They no longer want to be called ‘estate workers’ or ‘daily wage earners.’ Therefore, the productivity linked wage model works best as it facilitates flexibility of work and bestows dignity on employees as those who are self-managed rather than supervised.”

Rajadurai posits: “Under this scheme, workers can enjoy flexitime and not be subjected to strict supervision as in the traditional model. This model, which turns workers into self-managed agricultural entrepreneurs, is the only way forward for the tea industry.”

“And we don’t need any further proof of this than the success of the smallholder segment, which contributes 75 percent of the national green tea leaf input,” he adds.

A WAY OF LIFE Rajadurai asserts that “the planting vocation is not simply a job; it’s a way of life. Planters are on call 24/7 all year long, and remain responsible for providing custodial care to estate workers and their families from womb to tomb, in addition to their professional and work-related responsibilities and duties.”

He continues: “The job makes severe demands on their time – so one must be capable, mentally tough, physically fit and intellectually competent to face the rigours of managing an estate – although the perks are good.”

Moreover, agriculturists have to focus on obtaining global certifications, face audits, and conform to sustainable and carbon neutral practices while combatting the effects of climate change, apart from the core business of plantation management.

Aside from managing estates, there are exciting new opportunities in marketing, sustainability, human resources and performance management, Rajadurai enthuses. AI promises to be the ‘next big thing’ and its ability to benefit the industry is under review.

The ongoing brain drain is impacting the tea industry too. Some talented and trained planters have migrated following the economic crisis and there’s out-migration among plantation workers as well.

When the plantations were privatised in 1992, there were around 317,000 registered workers. Despite the increase in the country’s population since then however, the number of estate workers has declined to an estimated 115,000.

Rajadurai notes that the migration of youth to larger towns is irreversible because of social factors – although the plantations offer higher remuneration.

MODERNISATION Meanwhile, many planters are working to provide a buffer for the future by infusing automation and technology into the tea industry.

“Today, there’s automation in factories, land clearing and even plucking to a certain degree – with semiautomatic shears, handheld plucking machines, drone technology and so on. However, mechanising further will remain a challenge because of the hilly terrain, vintage of crops and very specific protocols in harvesting.”

A shortage of workers has led to each hectare being harvested only twice or three times a month – compared to the recommended practice of plucking four to five times a month – and this has resulted in lower yields.

Rajadurai concludes: “I am confident that if the tea industry is allowed to manage itself professionally without any undue external interference, Sri Lanka should be able to regain its 300 million kilogramme output in a few years’ time.”

Leave a comment