SWITZERLAND TODAY

THE FORMULA FOR SUCCESS

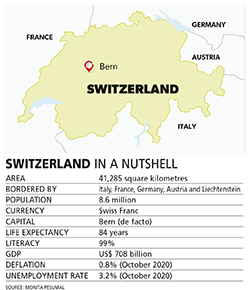

Monita Pesumal reveals what’s behind Switzerland’s longstanding monetary and political stability

Switzerland, which enjoys the world’s second highest per capita GDP of US$ 81,867, has consistently ranked among the 10 wealthiest countries on the planet. And its geographical location in Europe – and stance as a neutral state – has led to immense economic and political stability.

Not only is this Alpine nation among the most developed countries on Earth, Switzerland also lays claim to being the 18th largest economy in the world.

Not only is this Alpine nation among the most developed countries on Earth, Switzerland also lays claim to being the 18th largest economy in the world.

It has one of the most competitive economies thanks to its advanced services sector. Seventy-four percent of Swiss GDP is generated by services while the rest is powered by agriculture and industry. Two words – i.e. ‘Swiss made’ – define the country’s reputation for excellence in the manufacturing arena.

From defence equipment and tools – such as the popular Swiss army knife – to Rolex watches, pharmaceuticals and machinery, the nation’s precision and attention to detail, quality craftsmanship and strong work ethic have ensured that its products are respected globally.

It’s often been proven that one of the main reasons behind the country’s wealth is the ability of the Swiss to turn raw materials into products of intricate value – such as luxury chocolates, classic timepieces and complex new medicines.

In other words, what’s behind Switzerland’s wealth is the ability of the Swiss to innovate.

Although the Swiss Confederation sits outside the EU, it has access to trade with the bloc’s single market through multiple treaties and FTAs. The Swiss economy typically grows at an annual rate of around 1.7 percent.

However, like every other economy in the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a corresponding downturn. Lockdowns, working from home (WFH) and travel bans shook the economy in general except that of the pharma industry, which enjoyed a boom.

Most businesses saw their order books empty or cancelled and much of the services sector closed shop for long periods. For example, the watchmaking sector was among those that were most affected by the pandemic. Exports of Swiss watches plunged by almost a quarter in 2020 – the largest fall in a year since World War II.

Although the Swiss economy incurred a loss of 81 billion dollars due to the pandemic, government aid amounting to five percent of GDP prevented the downturn from worsening. This aid was far in excess of the stimulus measures extended during the 2007/08 financial crisis. Output fell by 3.3 percent in 2020, which was the worst downturn since 1975.

Employment was also hit hard as the annual unemployment rate rose to 3.1 percent last year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In December, the number of jobseekers topped 260,000, representing a 35 percent increase on 2019 figures and the highest since February 1997. The sectors

that felt the crunch the most were hotels and catering, transport, manufacturing and of course, tourism.

Reuters recently quoted the government’s chief economist stating that the nation’s economy could grow at more than double its usual rate in 2021 and 2022 with GDP expected to increase by around four percent each year as output recovers from the crisis.

According to the head of the Economic Policy Directorate at the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) Eric Scheidegger, the government expects the global economy to recover from the northern summer of this year. This should impact Switzerland’s export oriented economy, and GDP growth is projected at three percent and 3.1 percent in 2021 and 2022 respectively.

Switzerland is politically neutral and has a stable currency that’s detached from the euro. Zurich’s Credit Suisse Group and UBS Group form the back-bone of the banking sector while maintaining an international presence as well.

The Swiss code of banking secrecy that’s underpinned by legislation – which was enacted in 1934 – makes the disclosure of client identities a crime. As a result, this federal state became an offshore safe haven, much to the annoyance of other governments’ revenue departments, which claim that the country is fuelling tax evasion.

The Swiss code of banking secrecy that’s underpinned by legislation – which was enacted in 1934 – makes the disclosure of client identities a crime. As a result, this federal state became an offshore safe haven, much to the annoyance of other governments’ revenue departments, which claim that the country is fuelling tax evasion.

Its economy thrives on private and investment banking, and asset management services. However, for the first time in October 2018, the Swiss Federal Tax Administration officially began exchanging bank account data with tax authorities in other countries. This marked the end of Swiss banking secrecy in the interest of transparency.

Despite holding a quarter of the world’s wealth, Swiss banks are now in competition with Asia – particularly Singapore – when it comes to banking foreign funds. With secrecy no longer one of its trump cards, Swiss banks have few unique selling points with which to woo global millionaires.

The country’s largest bank UBS recently announced that it will close roughly a fifth of its Swiss branches during this quarter.

UBS announced these sweeping changes as the pandemic is boosting online banking over foot traffic and since persistently low interest rates are continuing to put pressure on the financial services industry.