STATE OF BALANCE

MONETARY AND FISCAL

TERMINOLOGY

Shiran Fernando explains the critical differences between fiscal and monetary policy approaches

Terminology in economics can be confusing to many and varying interpretations could lead to different outcomes. A case in point is the difference between fiscal and monetary policies. Most would assume they’re the same… but there are key differences.

Sri Lanka’s economic crisis has been at least partly due to a lack of understanding of these differences and what the future holds in terms of ensuring independence of monetary policy.

DIFFERING ROLES Fiscal policy in general refers to how a government collects revenue from the public, and spends it on education, healthcare, infrastructure and so on. It is determined by the finance ministry of a country and driven by the agenda of the government.

DIFFERING ROLES Fiscal policy in general refers to how a government collects revenue from the public, and spends it on education, healthcare, infrastructure and so on. It is determined by the finance ministry of a country and driven by the agenda of the government.

Monetary policy refers to the actions taken by the central bank of a nation: its role is to pursue objectives of price stability and in most cases, financial services industry stability.

A key feature of a responsible well functioning central bank is political independence. This is because such a bank is in charge of the public finances of a country and its citizens. Fiscal policy looks at what’s needed to secure financing for the policies of the state.

In Sri Lanka unfortunately, there have been too many instances of fiscal dominance over monetary policy, which has undermined the independence of the latter.

STATE OF BALANCE Monetary policy has to carefully navigate the impossible trinity, which comprises a country maintaining an open capital account, a fixed exchange rate and monetary policy independence at the same time.

However, you can only choose two of the three to maintain a nation’s economic conditions in a state of balance. Prior to the establishment of the Central Bank in 1950, Sri Lanka employed a currency board arrangement whereby a fixed exchange rate prevailed.

Between 1950 and 1977, monetary policy shifted to peg the currency against the British Pound Sterling first and then the US Dollar. As a result, domestic inflation was linked to foreign inflation and there was no monetary independence.

With the opening up of the economy, management of our currency saw a managed floating exchange rate system being adopted and monetary policy gravitated towards monetary aggregate targeting. Monetary aggregate targeting means focussing on the money supply and reserve money, and monitoring the movement of indicators such as credit to the private sector.

This wasn’t successful in Sri Lanka as it has consistently run twin deficits – i.e. the fiscal and current accounts. As a result, the exchange rate swung between being fixed to a crawling peg in certain periods.

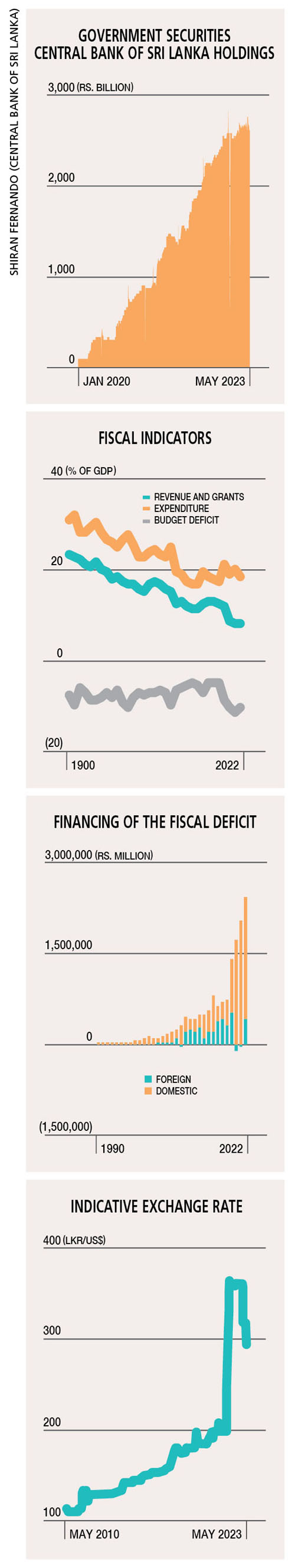

FISCAL POLICY Since 1950 (barring 1955), Sri Lanka has always run a budget/fiscal deficit, which was financed through domestic or foreign sources. The recent crisis saw the country losing access to international capital markets, which it relied on from 2007 to 2019.

With credit rating agencies downgrading Sri Lanka’s creditworthiness, the country lost access to foreign financing through international sovereign bonds (ISBs). So from 2020, the government has had to rely on domestic financing through the banking system.

Most of this financing was by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka as it printed money, and purchased government securities (T-bills and bonds) and lent it to the Treasury to manage the deficit. This is what is meant by monetisation of the deficit.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK The current legislation governing the Central Bank is the Monetary Law, which was enacted in 1949 with several amendments being made up to 2014.

And the Central Bank was planning to reform this law at the time of the 16th programme with the IMF in 2016 and a bill was published in 2019 with the support of the UN agency. However, it was not enacted when the government changed.

This has been taken forward under the 17th programme of the IMF, which commenced in March. A key change to the existing law will be the removal of fiscal dominance over monetary policy as the Secretary to the Ministry of Finance will not be included in the Monetary Board.

This is the crucial first step towards ensuring that the Central Bank doesn’t continue to finance the fiscal deficit and is supported by provisions to prevent deficit financing except in extreme cases.

PRICE STABILITY The way forward for monetary policy will be in terms of inflation targeting with the primary objective of the Central Bank being domestic price stability.

Inflation targeting is a process whereby the central bank of a country announces its target for inflation and uses monetary tools to move towards it. Many countries such as New Zealand and Canada have leveraged inflation targeting to keep that key economic indicator in check while ensuring monetary policy independence.

This is a crucial piece of reform that – if it is passed in parliament – will ensure that one of the causes of the current crisis won’t be a problem in the future.

Leave a comment