G7 SUMMIT

TAKEAWAYS FROM HIROSHIMA

Samantha Amerasinghe analyses some of the key decisions made by G7 leaders

Expectations were high at this year’s G7 summit in Hiroshima, Japan. In addition to the Group of Seven leaders, representatives from the EU and a broader array of countries – such as South Korea, India and Australia – met to discuss the most pressing challenges the world is facing.

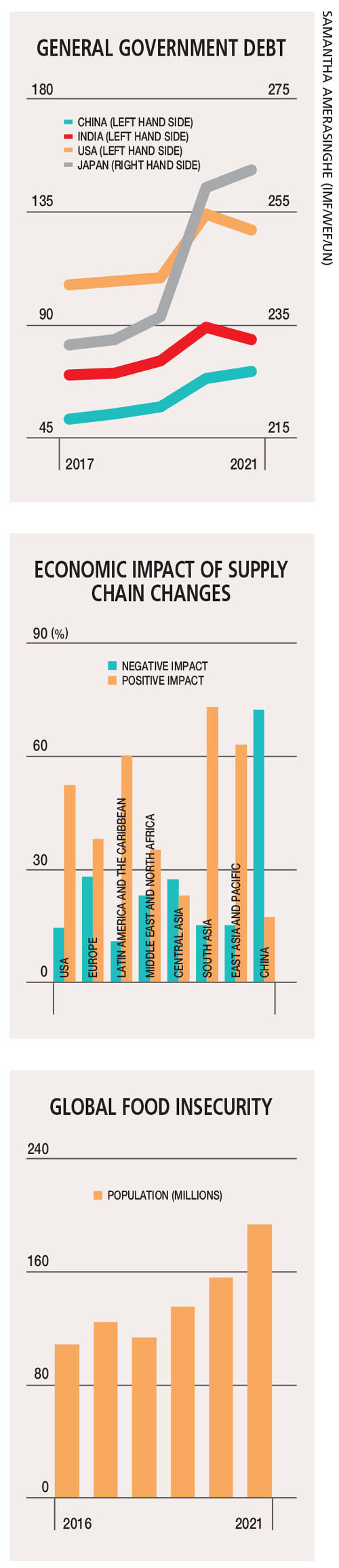

This meeting was particularly important because the planet has plenty of challenges to address right now, spanning the gamut from climate change, Russia’s war in Ukraine and a worldwide food crisis to the global debt issue. These multiple crises are pushing increasing numbers of people into extreme poverty.

The core issues debated and discussed focussed on the war in Ukraine, the West’s supply chain dependency on China, nuclear nonproliferation, economic security and cooperation, and taking meaningful action on the climate crisis.

Progress on cooperation against economic coercion and the G7’s continued support for Ukraine were notable achievements. On issues related to climate, health and food security however, the summit did not achieve anything new.

Progress on cooperation against economic coercion and the G7’s continued support for Ukraine were notable achievements. On issues related to climate, health and food security however, the summit did not achieve anything new.

China was singled out on many fronts including issues related to Taiwan, nuclear arms and economic coercion, which underscored the tension between Beijing and the grouping of powerful nations.

A key takeaway was the shift in language on economic policy towards China. Leaders emphasised that G7 economic policies aren’t designed to harm or decouple from China but are aimed at diversification and ‘de-risking.’

This shift in language indicates that the US and its allies understand the risks of deep economic engagement but also realise that a complete severance of economic ties isn’t realistic.

By de-risking, G7 countries will reduce excessive dependence on critical supply chains in everything from semiconductor chips to minerals but still want constructive and stable relations with China.

Reducing exposure to the world’s second largest economy is a direct policy measure aimed at thwarting China’s economic progress. So it’s not surprising that the People’s Republic expressed strong dissatisfaction with the G7’s joint statement at the summit’s conclusion.

Japan strategically selected the city of Hiroshima to promote its goal of nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation because it is the site of the first ever nuclear bombing. The fact that G7 leaders gathered for discussions in Hiroshima was symbolic in the context of the Ukraine war and a growing risk of the use of weapons of mass destruction (WMD).

The impact of the surprise visit by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to the summit was twofold.

From a public relations standpoint, it was instrumental in ensuring that the spotlight stays on Ukraine. In addition, he also garnered further backing from the G7 with its leaders announcing a set of concrete actions to intensify their support to counter the negative impacts of Russia’s war on the rest of the world.

Though sanctions have failed to stop Russia’s invasion so far, US President Joe Biden has pledged further military assistance worth US$ 375 million.

Climate and development finance were also top priorities – especially because they are increasingly being perceived as areas where China and Russia compete with the G7. Consequently, this has led to greater cohesion on jointly mobilising 100 billion dollars in climate finance annually by 2025.

To achieve their goal of net zero emissions by 2050 and address the current energy crisis caused by the Ukraine war, G7 leaders pledged to work together to ensure that regulations and investments will make clean energy technologies more affordable for all countries.

They highlighted the urgent need to accelerate the clean energy transition as a means of increasing energy security as well. However, only vague commitments were made regarding phasing out fossil fuels and meeting the net zero carbon emissions goal.

In terms of combatting extreme poverty, the G7’s leaders highlighted their concerns that serious challenges to debt sustainability are undermining progress towards achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and reiterated the urgency of addressing debt vulnerabilities in low and middle income countries.

However, it seems there is little urgency from prosperous industrialised nations to fund development assistance. The World Bank estimates that to address the global challenges of climate change, conflicts and pandemics, average annual spending on developing countries should be in the region of US$ 2.4 trillion from 2023 to 2030.

This is 10 times what the richest nations presently spend on overseas development assistance each year.

The unfortunate reality is that international assistance is now a secondary priority as domestic issues and Russia’s war in Ukraine are dominating agendas.

Looking ahead to 2024, Italy will assume the role of the G7 presidency in January. Though Italy’s priorities are currently unknown, it’s likely that the focus will remain on continued support for Ukraine. China also promises to be a continued concern.

Creating a mechanism to restructure the debt of developing countries, increasing green investment projects and advancing food security are other likely priorities for Italy. The 2024 G7 summit will represent another chance for leaders to build on the commitments made in Hiroshima.

Leave a comment