POST-COVID ECONOMY

UNEQUAL ECONOMIC REVIVAL

Samantha Amerasinghe highlights several risks in inequitable global recovery

At a time when nations need to collaborate more to address compounding global hazards, a divergent economic recovery from the pandemic induced crisis risks deepening divisions across the world. In many countries, rapid progress on vaccination, accelerated digitalisation and a return to pre-pandemic growth rates suggest better prospects for 2022… and beyond.

Meanwhile, some others could be weighed down for years as they struggle to provide even the first dose of a vaccine to their citizens, combat the digital divide and find new sources of economic growth.

So it wasn’t surprising that ‘working together, restoring trust’ was the dominant theme at the virtual Davos summit this year since the pandemic has intensified a global trust crisis.

Let’s take a dive into the global risks and examine some key findings of the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Risks Report 2022.

Let’s take a dive into the global risks and examine some key findings of the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Risks Report 2022.

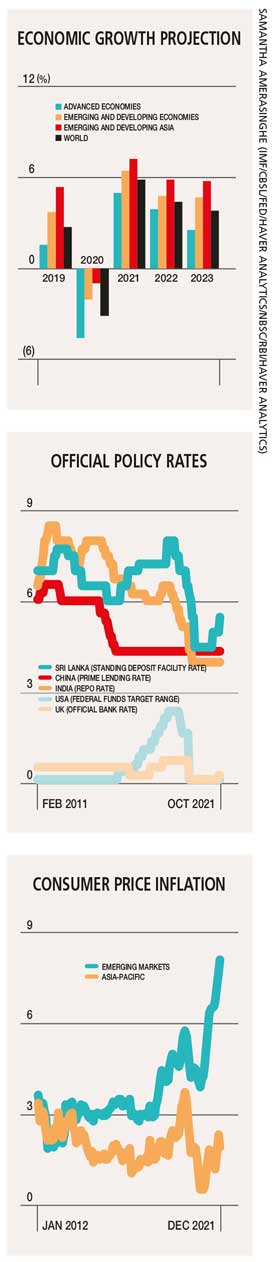

The potential knock on economic risks from the pandemic include supply chain disruptions, which are weighing on activity and contributing to higher inflation. These are adding to pressures from strong demand, and elevated food and energy prices.

Moreover, the world economy has sailed into much choppier waters on the back of record debt, labour market gaps, protectionism and educational disparities that nations will need to address in order to thrive again.

Such difficulties are masking the visibility of emerging challenges including climate change. Economic overhang from the pandemic will make it difficult to ensure a coordinated and timely approach to such issues – not only because of polarised societies but also since governments are still in crisis management mode.

The report presents the results of the latest Global Risks Perception Survey (GRPS), and an analysis of key risks arising from the current economic, societal, environmental and technological tensions. The key findings indicate that societal risks in the form of an erosion of social cohesion, livelihood crises and deteriorating mental health have worsened the most since the onset of the pandemic.

Over the next five years, societal and environmental risks are deemed to be the most concerning. Over a 10 year horizon however, environmental risks will dominate; and climate action failure, extreme weather and loss of biodiversity will rank as the three most severe risks.

The debt crises and geo-economic confrontations will also feature prominently. With interest rates rising, low income countries – of which 60 percent are already in or at high risk of debt distress – will find it increasingly difficult to service their debts.

Although the threat of inflation on the global economy continues to capture headlines and was a hot topic at the Davos summit, elevated inflation has not been cited as a key risk. And Asia is in no rush to aggressively raise interest rates.

Inflation rates across the Asia-Pacific region remain elevated but are coming off a very low base. If inflation is prevalent, it tends to be imported or supply shock driven – usually in food and energy with the price of crude oil on the rise.

Furthermore, since national lockdowns weren’t necessary, this didn’t result in the big switch from services to goods as in the West. And due to economies opening up only gradually, the scale of demand shocks that were evident elsewhere weren’t seen as much.

Supply chain disruptions and the resulting shortages (aside from semiconductors) were also largely downstream and located away from Asia. Moreover, where there were supply chain disruptions, local alternative suppliers were available to step in with ease, thanks to trade diversification away from China in recent years.

Of course, there are exceptions but inflation in Asia is generally not a major problem and there has been no overarching requirement for regional central banks to support currencies with higher rates. Current account balances have also remained in check with the pandemic restoring equilibrium even where external balances have historically been in deficit.

Even as recoveries continue however, a troubling divergence in prospects across countries persists.

While developed economies are projected to return to pre-pandemic levels this year, several emerging markets and developing economies are expected to see sizeable output losses in the medium term. Perhaps this is another reason why emerging economies may be reluctant to raise rates.

Monetary policy is at a critical juncture in most countries. Where inflation is broad based alongside a strong recovery – as in the US – or high inflation runs the risk of becoming entrenched, extraordinary monetary policy support should be withdrawn. Several central banks have already begun raising interest rates to get ahead of price pressures.

The US Federal Reserve maintains that it will end its extraordinary policy support this year. In contrast, the European Central Bank (ECB) has been reluctant to raise rates to combat rising inflation and insists that many factors – including temporary ones – have led to high inflation.

Though uncertainty may linger for some time, this may well be the year that the world finally escapes the grip of the pandemic – but not without greater collaboration to counter the global risks.

Leave a comment