ORGANISATIONAL GROWTH

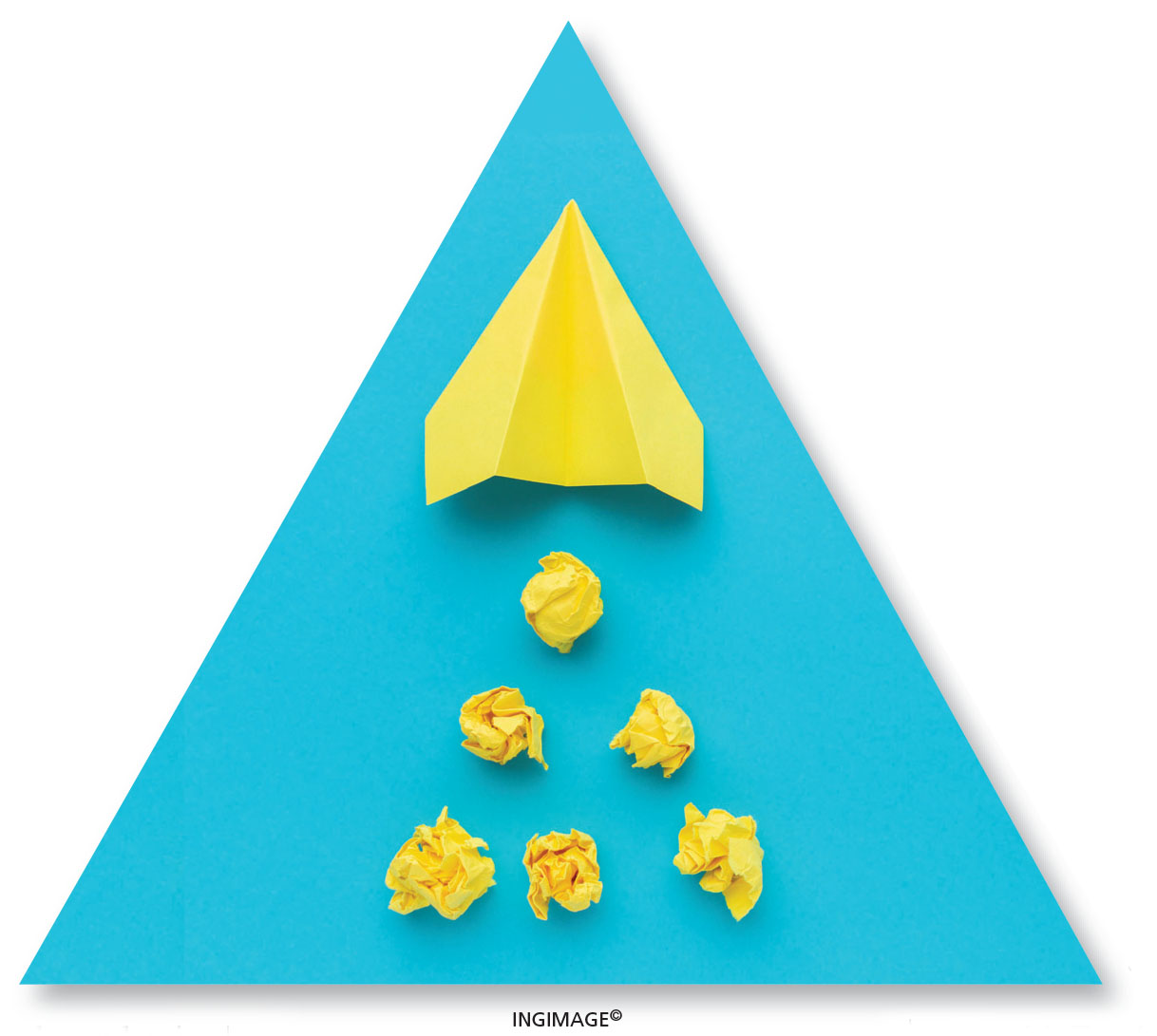

CULTURE OF INNOVATION

Good for biz growth and performance

BY Jayashantha Jayawardhana

A culture that’s conducive to innovation is not only good for sustained growth and business performance but also favoured by existing employees and potential candidates at every level of the hierarchy.

Most people perceive innovative cultures at the workplace to be good fun and are proud to work for a dynamic business that makes good headlines in the press.

So what constitutes an innovative culture? It is tolerant of failure, willing to experiment, psychologically safe, highly collaborative and nonhierarchical. There’s strong research to support the idea that these types of behaviour translate into better and more innovative performance.

If what makes an innovative culture is universally known, and if leaders and employees are so gung ho about it, why isn’t it ubiquitous? And why is this culture so hard to introduce to and mainstream in organisations?

It’s because all those praiseworthy and universally loved behavioural norms are only half of the picture. The other half is much less popular – and that is what’s going to be discussed here.

Senior Associate Dean for Faculty Development at the Harvard Business School Prof. Gary Pisano writing in the Harvard Business Review (HBR) says he believes innovative cultures are misunderstood. He writes: “The easy to like behaviours that get so much attention are only one side of the coin. They must be counterbalanced by some tougher and frankly less fun behaviour.”

“A tolerance for failure requires an intolerance for incompetence. A willingness to experiment requires rigorous discipline. Psychological safety requires comfort with brutal candour. Collaboration must be balanced with individual accountability. And flatness requires strong leadership,” he adds.

Pisano continues: “Innovative cultures are paradoxical. Unless the tensions created by this paradox are carefully managed, attempts to create an innovative culture will fail.”

TOLERANCE When it comes to innovation, some failures are essentially part of the package since we’re entering unknown and uncharted territory. So there’s a high level of uncertainty as to how a promising idea or concept will turn out. Highly competent people could do their very best but still fail.

This is the tolerable side of the failure equation. Since failing is equally likely to result from sheer incompetence, exceptionally high performance standards must be set for all.

EXPERIMENTATION Organisations that embrace experimentation are comfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity. They’re content not to know all the answers upfront and experiment to learn rather than produce an immediately saleable product or service. But they do experiment very methodically.

Without discipline, almost anything can be justified as an experiment. Disciplined cultures hand-pick experiments on the basis of their potential learning value and design them rigorously to yield as much information as possible relative to the costs.

CANDOUR In their book titled Creativity, Inc., authors Amy Wallace and Edwin Catmull spell out ‘brutal candour’ as being one of the factors crucial to Pixar’s amazing and unrivalled success in the animation film industry, starting with Toy Story.

In such psychologically safe environments, people aren’t afraid to speak their minds and share ideas openly without fear of reprisal. Although it seems so obvious and intuitive to speak the truth, we know candour is one of the rarest commodities in the corporate world today.

COLLABORATION Contrary to popular belief, collaboration and collective responsibility aren’t at odds with individual accountability. Playing as a team that pulls together is vital for a well functioning and innovative system. The same goes for the fulfilment of individual responsibilities and decisions.

For instance, while there’s feedback coming from several sources at Pixar, the director chooses which to take and what to disregard, and is held accountable for the content of the movie.

LEADERSHIP In culturally flat organisations, people are given ample leeway to take action, make decisions and voice their opinions. They can typically respond quickly to fast changing circumstances because decision making is decentralised and closer to the sources of relevant information. Nevertheless, an absence in hierarchy doesn’t mean a lack of leadership.

Paradoxically, flat organisations require stronger leadership even more than hierarchical ones. They descend into chaos when the leadership fails to set clear strategic priorities and directions. Amazon and Google, which are culturally flat organisations, have strong leaders at the helm.