HISTORY LESSONS

GOING FORWARD LOOKING BACKWARDS

BY Priyan Rajapaksa

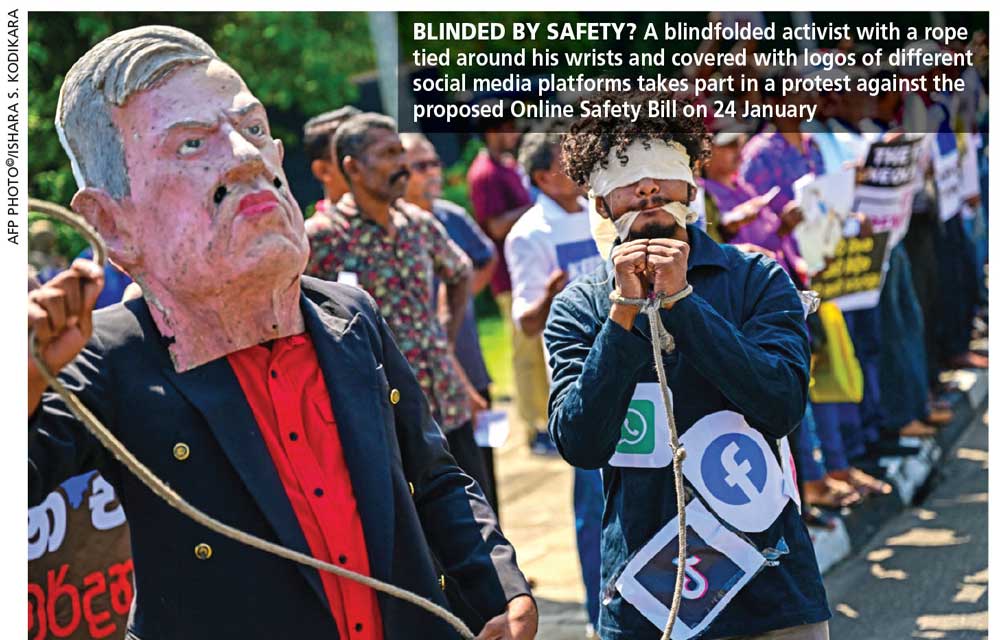

It was sad to listen to the charade of a debate on the Online Safety Bill (OSB) in Sri Lanka’s parliament recently. When a steamroller is used, the smaller stones get crushed; and it was the same in 1978 when a larger steamroller was at hand to bring to life the hydra of the executive presidency – and the country burned.

I don’t want the country to burn; but steamrolled debates don’t contribute to true democracy.

Irish wit George Bernard Shaw wrote: “If history repeats itself and the unexpected always happens, how incapable must man be of learning from experience.”

Shaw’s words brought to mind a book titled ‘The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,’ originally published in 1776 and authored by English historian and politician Edward Gibbon.

I don’t have the language skills to rewrite Gibbon’s captivating work so I’m reproducing an extract of what he wrote about Augustus Caesar. Some words and phrases are ominous, and I leave it to the reader to digest or discard them according to his or her political views.

So teleport yourself to Augustus Caesar’s Rome of 27 BC when the republic was turning into a monarchy.

IDEA OF A MONARCHY The obvious definition of a monarchy seems to be that of a state in which a single person – by whatsoever name he or she may be distinguished – is entrusted with the execution of the laws, management of revenue and command of the armed forces.

But unless public liberty is protected by intrepid and vigilant guardians, the authority of so formidable a magistrate will soon degenerate into despotism.

The influence of the clergy in an age of superstition might be usefully employed to assert the rights of humankind. But so intimate is the connection between the throne and altar that the banner of the church has very seldom been seen on the side of the people.

A martial nobility and stubborn commons – possessed of arms, tenacious of property, and collected into constitutional assemblies – form the only balance capable of preserving a free constitution against enterprises of an aspiring prince.

SITUATION OF AUGUSTUS Every barrier of the Roman constitution had been levelled by the vast ambition of the dictator and every fence had been extirpated by the cruel hand of the triumvir.

Following the victory of Actium in 31 BC, the fate of the Roman world depended on the will of Octavianus (surnamed Caesar, by his uncle’s adoption; and afterwards, Augustus, by the flattery of the senate).

The conqueror was at the head of 44 veteran legions, conscious of their own strength and the weakness of the constitution – habituated over 20 years of civil war to every act of blood and violence, and passionately devoted to the house of Caesar from whence alone they had received and expected the most lavish rewards.

And the provinces, long oppressed by ministers of the republic, sighed for the government of a single person who would be the master – not the accomplice – of those petty tyrants.

The people of Rome, viewing with a secret pleasure the humiliation of the aristocracy, demanded only bread and public shows; and they were supplied with both by the liberal hand of Augustus.

And the rich and polite Italians, who had almost universally embraced the philosophy of Epicurus, enjoyed the present blessings of ease and tranquillity, and suffered not the pleasing dream to be interrupted by the memory of their old tumultuous freedom.

With its power, the senate lost its dignity; and many of the noble families were extinct. The republicans of spirit and ability had perished in the field of battle or proscription.

The door of the assembly had been designedly left open for a mixed multitude of more than a thousand persons who reflected disgrace upon their rank instead of deriving honour from it.

SENATORIAL REFORMS The reformation of the senate was one of the first steps in which Augustus laid aside the tyrant and professed himself the father of his country.

He was elected censor; and in concert with his faithful Agrippa, he examined the list of senators, expelled a few members whose vices or obstinacy required a public example and persuaded nearly 200 to prevent the shame of an expulsion by a voluntary retreat.

Augustus also raised the qualification of a senator to about 10,000 pounds, created a sufficient number of patrician families and accepted the honourable title ‘Prince of the Senate,’ which had always been bestowed by the censors on the citizen who was the most eminent for his honours and services.

But while he thus restored dignity, Augustus destroyed the independence of the senate. The principles of a free constitution are irrevocably lost when the legislative power is nominated by the executive.

RESIGNS USURPED POWERS Before an assembly thus modelled and prepared, Augustus pronounced a studied oration, which displayed his patriotism and disguised his ambition.