GLOBALISATION ON EDGE

DAMN THE LEVEL PLAYING FIELD

Gloria Spittel argues that globalisation is creating disparities between social classes and nations

Are there winners and losers in globalisation? Is there really such a dichotomy arising from the causes and effects of globalisation? Many would say that such a dichotomy is simplistic at best and false at the other end of the spectrum.

Well, both these arguments hold true as nothing is simple when it comes to globalisation; and by that line of thought, the dichotomy is false. It is also true (and has been documented) however, that the effects of globalisation and its inherent capitalistic nature have benefitted some more than others.

This in turn is a major cause for inequality in global society today.

A study conducted by World Bank (WB) economist Branko Milanovic and released in 2013 states that globalisation has mostly benefitted – and continues to benefit – an emerging global middle class in countries such as China, India and Indonesia, and the world’s top one percent from traditional developed economies. However, people at the bottom of the income ladder and lower middle class have garnered only incremental gains.

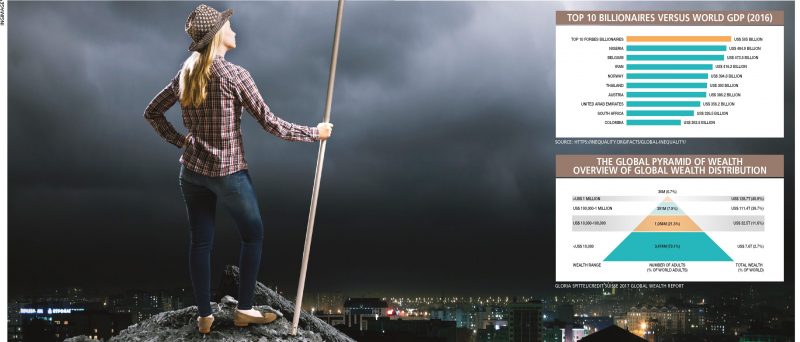

The study used a WB database containing household data from over 120 countries between 1988 and 2008, which marked the beginning of the global financial crisis. However, the findings of this study remain largely relevant. For instance, the 2016 annual Forbes billionaire list’s aggregated wealth was more than the GDP of countries with large populations, emerging economies (including Nigeria, South Africa, Thailand, Iran and the UAE) and many global cities.

Another report released by Credit Suisse last year reveals that a staggering 45.9 percent of global household wealth is controlled by a mere 0.7 percent of the world’s population. In terms of numbers, this amounts to 36 million individuals with a wealth of US$ 128.7 trillion.

Below this rung, nearly 40 percent of global wealth is owned by less than eight percent of the world’s population. And the base of the wealth pyramid represents seven in 10 of the global population with a combined wealth of only 7.6 trillion dollars.

Class inequality is one of the starkest examples of globalisation’s capitalistic nature because it benefits only a few.

The sad reality is that absolute poverty across the world has declined but this isn’t commensurate with the rich becoming richer. As such, Credit Suisse in its 2017 report anticipates a further 22 percent rise in dollar millionaires by 2022 and only a four percent drop in the number of individuals with US$ 10,000 or less at the base of the pyramid during the same period.

Disparities in income and inequality have ramifications across other areas of everyday life – this includes fewer personal opportunities for social mobility due to the increasing cost of education and healthcare in developed and emerging countries, and stagnant lifestyles and unmet aspirations in emerging developing and underdeveloped countries.

These factors create a potent mixture for political and social chaos, and have been cited as reasons for Donald Trump’s election as US president and the UK’s Brexit vote. The more insular and protectionist the world becomes about people and trade, the less opportunities there are for individual and global growth in this globalised capitalist world.

The effects of globalisation have also been felt at macro level by affecting countries differently; and in some cases, increasing divisions while creating stereotypes that have led to misunderstandings and potential conflict.

An example of this undercurrent of conflict is the misconception that labourers from South and East Asian countries deliberately pursue low paid, low cost manufacturing in order to ‘steal’ jobs from developed countries. In fact, the outsourcing of work, whether in manufacturing or services, is more complex and revolves around ethical questions concerning unregulated and unsafe workplace practices, and working conditions.

In addition to individual and national issues, globalisation also plays a role in issues such as climate change. Year after year, we hear of rising temperatures, and while it is now commonly acknowledged that policies and their enactment are necessary to stop (and hopefully reverse) this trend, the buck is often passed around at large international meetings.

For instance, the 2016 Paris Agreement on climate change sought to mitigate rising global temperatures but the following year, the US pulled out citing Trump’s ‘America First’ policy. While the United States is one nation among the nearly 200 signatories that have signed the agreement, the move is an example of the insular attitudes and protectionist values that favour some.

Furthermore, globalisation and its rampant counterpart consumerism continue to increase global waste; this not only has a negative impact on the environment but also adversely affects the sourcing of minerals and raw materials necessary to manufacture products.

Globalisation has had the unintended effect of creating disparities between social classes and nations. It has also caused environmental harm across the world. So how does the world move away from a system that largely benefits a few? And what changes can be instituted – and how?

Globalisation is one such concept advocated by developed nations. When powerful nations initiate such international policies, traditional and developing economies are tempted or at least have no choice other than to join the club.

Reviewing the situation so far and considering the agendas of powerful nations, it is reasonable to accept the fact that globalisation too is another concept that will swing to the tune of those who are privy to hold power. The inner purpose of these powerful countries is taking whatever the (greater) bundle of benefits and rejecting what is not acceptable to them in the long run.

Exiting from the Paris agreement on climate change while being a signatory is another stubborn move of resistance by the USA. Accordingly, enjoying a selfish approach in a global concept can leave room for political and social chaos to spark at the worst time or place in the worst economic climate, which can be harmful in the long run.

It cannot be fathomed that these concept initiators propelled a breeding ground for unintended ill effects to boom such as the Trump election and Brexit vote. Nevertheless, these initiators hold the key to mitigate inequalities. One way is changing their attitude to relax their bargaining power to spread the privileges to a larger segment of society, especially the marginalised. This will allow for more flexibility and access for employment, health and education. Most of all, making room for their voices and rights!

I fully agree with these comments.