GLOBAL TRADE

BOUNCING BACK ALBEIT SLOWLY

Samantha Amerasinghe analyses the post-pandemic landscape for global trade

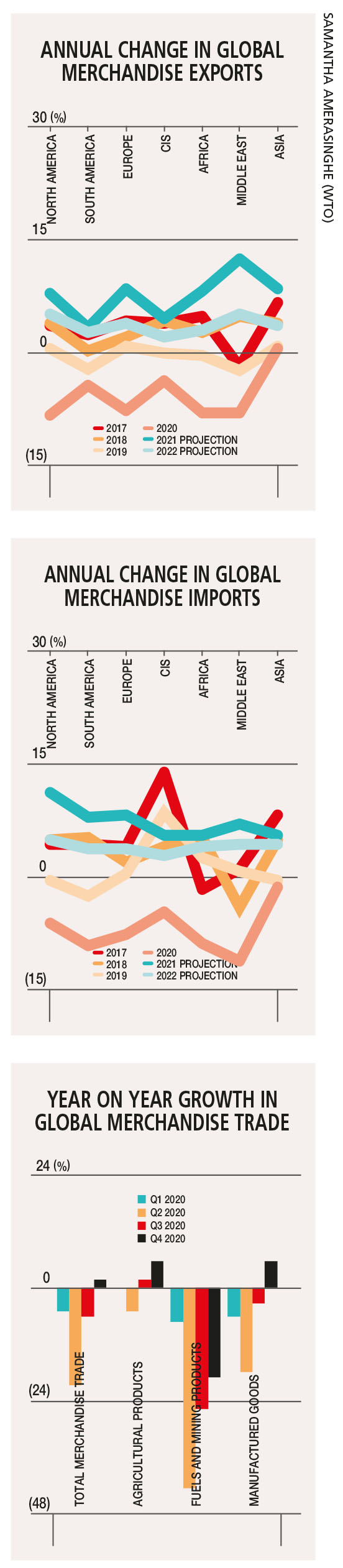

World trade is primed for a strong but uneven recovery when the COVID-19 shock subsides. According to recent WTO estimates, global merchandise trade volumes are expected to increase by eight percent this year, having fallen 5.3 percent in 2020.

Nonetheless, the recovery will be gradual with trade growth expected to slow to four percent next year. This pace of expansion given the pandemic’s lingering impact will leave trade below its pre-pandemic trend.

Nonetheless, the recovery will be gradual with trade growth expected to slow to four percent next year. This pace of expansion given the pandemic’s lingering impact will leave trade below its pre-pandemic trend.

The pandemic poses the greatest risk to the global trade outlook as a resurgence of the virus could undermine a sustained recovery. The outlook continues to be marred by slow vaccine roll outs (particularly in developing countries), regional disparities and the prolonged weakness in services trade.

Overall, three vital factors were responsible for the smaller than expected contractions in growth and trade at the beginning of the pandemic.

Arguably, the biggest factor was the strong monetary and fiscal response (which was greater in scale than the 2007/08 global financial crisis) by many governments, which helped prevent a larger fall in global demand that would have reduced trade even further.

Fiscal support was particularly important as it boosted personal incomes, which in turn enabled relatively high levels of consumption and propped up exports – more than would have been the case otherwise.

Second, lockdowns and travel restrictions caused consumers to shift spending away from non-traded services and towards goods, while adaptation and innovation by businesses (in terms of manufacturing supply chains and households with the shift to remote working) helped generate demand.

Finally, trade policy restraint by WTO members prevented protectionism from strangling world trade despite continuing challenges, notably around vaccines.

Although trade has held up relatively well, the 2021 fore-cast is subject to downside risks. In the short term, risks are centred on pandemic related factors – viz. insufficient production and distribution of vaccines or emergence of new vaccine resistant strains of COVID-19.

Although trade has held up relatively well, the 2021 fore-cast is subject to downside risks. In the short term, risks are centred on pandemic related factors – viz. insufficient production and distribution of vaccines or emergence of new vaccine resistant strains of COVID-19.

Over the medium to long term, the main concern is public debt and deficits, which could weigh on economic growth and trade, particularly in heavily indebted developing countries.

The WTO’s upside scenario shows trade returning to pre-pandemic levels in the fourth quarter of this year due to an acceleration of vaccine production and distribution, allowing for a quicker relaxation of containment measures.

This scenario is expected to add one percentage point to global GDP growth (estimated at 5.1% by the WTO) and about 2.5 percentage points to trade volume growth this year.

Other factors that could impact global trade from a policy standpoint include the new trade agreements that have come into force, and the President Joe Biden administration’s trade policy agenda and thorny relations with China.

Although the prospect of a ‘hard Brexit’ did not materialise as a UK-EU trade agreement was ratified at the eleventh hour on 31 December 2020, the situation unfolding since January proves that Brexit has been costly with Britons experiencing the first adverse side effects.

These include lower economic growth, additional red tape with the export of goods to the European Union, a higher cost of living and loss of business with banking giants moving hundreds of billions of euros to their new or expanded hubs across the bloc.

Many of the effects will take time to play out – with Britain outside the EU’s single market and customs union, trade with the bloc has been hampered but the full extent of the damage won’t be clear until businesses fully reopen post-lockdown.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement was signed on 15 November 2020. Once it comes into force following ratification (most likely this year), it’ll be the world’s largest regional trade agreement in terms of GDP (RCEP countries account for about 29% or US$ 25.8 trillion of global GDP).

The RCEP is a multilateral regional agreement extending and strengthening free trade between ASEAN member states, and their existing trade partners China, Japan and South Korea, as well as Australia and New Zealand. It’s also the first such agreement to include mainland China.

It is worth highlighting that RCEP countries have coped better with the pandemic than many other regions and much of the global recovery is being driven by them.

However, it’s not all smooth sailing. Reaping the potential benefits of this regional free trade agreement (FTA) will depend on how well the major challenges of bringing together such a diverse group of countries with divergent political and economic interests will play out.

Multilateral trade policy will need to evolve to better reflect the global challenges that lie ahead – the post-pandemic recovery, resurgence of more restrictive trade policies and trade wars, and climate change.

Despite the Biden administration pursuing a more multilateral approach to trade policy by repairing ties with the US’ traditional partners and engaging with international bodies such as the WTO, a stronger stance on China will likely remain. However, with the emergence of the RCEP, America’s trade policy is likely to pivot towards Asia (as it did during the Obama administration), offering a glimmer of hope.

With the sobering reality that the pandemic is not yet under control and far from over, at least global trade will bounce back even though the pace of recovery will be painfully slow.