Europe’s new space budget to enable CO2 mapping

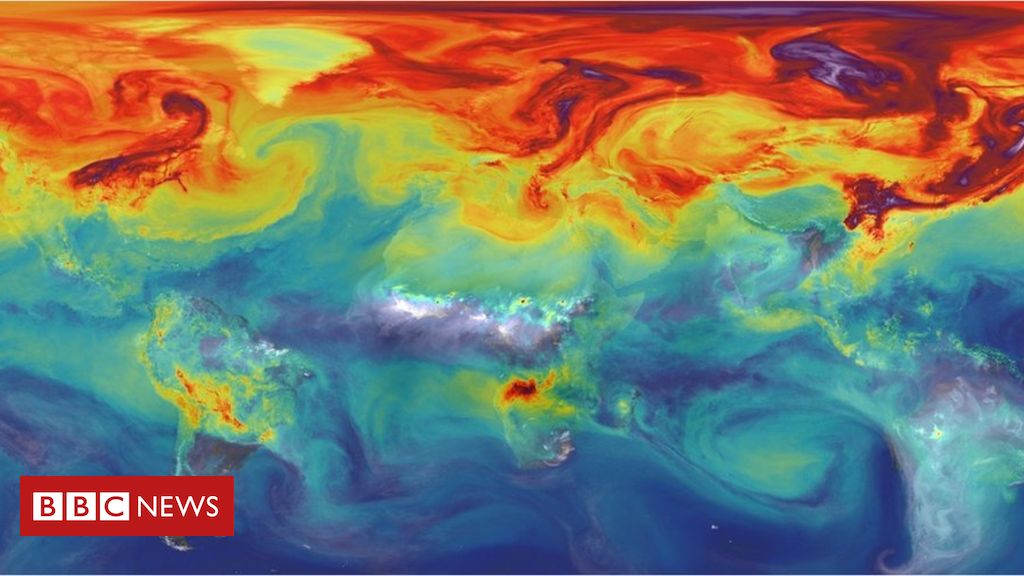

Europe will press ahead with a network of satellites to track carbon dioxide emissions across the globe.

They will be developed out of a new European Space Agency (Esa) budget agreed in Seville, Spain.

Research ministers on Thursday approved a package of proposals worth some €14.4bn (£12.3bn/$15.9bn) over the next five years.

As well as the new CO2 monitoring system, the funds will also pave the way for missions to the Moon and Mars.

“You’re looking at a very happy DG,” said Jan Wörner, the director general of Esa, after getting pretty much everything he wanted from the “Space19+” Ministerial Council. “It always looks so simple. But it took more than two years of preparations to get here. Unbelievable!”

While there were multiple projects being considered here, it is the support given to Earth observation (EO) that catches the eye.

Delegates from 22 nations had been asked to pledge €1.4bn (£1.2bn) to expand the so-called Copernicus programme, which flies a suite of Sentinel satellites to track the health of the planet. At the end of two days of discussions, the actual figure committed was €1.8bn (£1.5bn).

The extra cash will enable Esa to improve the performance of the new Sentinels.

The three spacecraft that will make up the carbon dioxide constellation will have their resolution increased, to be able to map grid squares across the globe of just 2km across. And their swath – the width of their vision – will be increased from 200km to nearly 300km. In addition, the satellites will be given more instruments to help tease apart the CO2 coming from natural sources from that which is being produced by humans.

The enhanced capability is expected to be a potent tool in helping all nations – not just European ones – better understand their carbon footprint.

Esa wants to get the new Sentinel system launched by 2025/26, to align its mapping service with the global stocktake of emissions that will be undertaken in 2028 as part of the Paris climate deal.

As well as CO2-sensing satellites, the expanded Copernicus programme will develop five other systems to measure a range of Earth variables, from the extent of Arctic sea-ice to the temperature of the global land surface.

The impressive backing for these new Earth observing spacecraft was driven largely by Germany, which pledged €518m (£444m) of the total €1.8bn. Its industry will now get the bulk of the R&D contracts.

“Earth observation is the cornerstone of German space policy,” said Thomas Jarzombek, from the nation’s Economic Affairs Ministry.

“People are more and more interested in climate change and what we can do to protect ourselves against it. Information is key because we can only really act against climate change if we understand what it going on. Copernicus gives us better data,” he told BBC News.

It should be stated that Copernicus is a joint venture between Esa and the EU, with the latter covering 70% of the overall costs. Brussels’ contribution to the expansion programme has yet to be determined.

“There is today about €6bn (£5.1bn) foreseen as part of the [EU] budget for space. And we look forward to completing the constellation with the recurring [satellites] which are to be paid for by the EU along with, of course, their operation,” explained Esa EO director, Josef Aschbacher.

Across the entire Space19+ budget request, the top contributing countries were:

- Germany – €3.3bn (£2.8bn), which is a 23% share of the total budget

- France – €2.7bn (£2.3bn), which is an 18.5% share

- Italy – €2.3bn (£1.8bn), which is 16%

- UK – €1.6bn (£1.4bn), which is 11.5%

The UK’s subscription after this meeting will rise from €355m (£304m) per year to €440m (£377m) per year.

Graham Peters, the chair of the trade association UKSpace sees this as a positive outcome.

“It gives us a fantastic platform upon which we can now build the national space programme to develop new sovereign capabilities and to start collaborating more globally to drive exports,” he said.

Other highlights to come out of Space19+

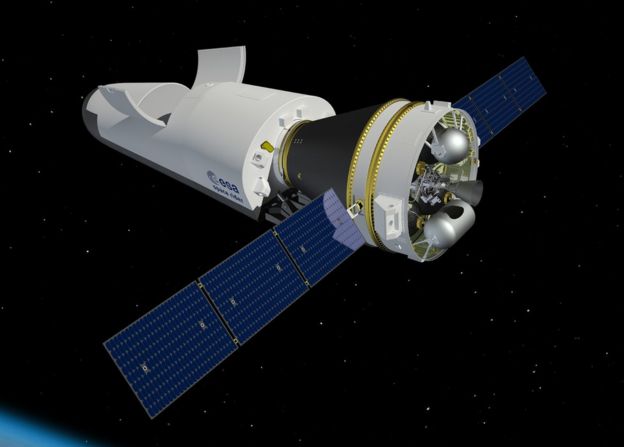

Human spaceflight and robotic exploration – This near-€2bn programme was 98% subscribed. It will make Esa an important partner in the US space agency’s (Nasa) grand plan to return astronauts to the Moon – known as Artemis. Member states committed money in Seville to fund two propulsion units for the Americans’ Orion crew capsules. Cash was also made available to start development work on modules that will attach to a lunar space station called Gateway. On Mars exploration, the agency now has the money to advance missions to bring rock samples back to Earth from the Red Planet. Technologies for this include a surface rover that UK engineers would very much like to build.

Science – Valued at €2.8bn, all member states must contribute to the projects that fall under this umbrella. The 10% increase in this budget line is the first real-terms increase in 25 years. One of the benefits will be to provide the funding necessary to align the development path of a couple of very exciting observatories. Esa is building a big X-ray space telescope called Athena and a constellation of satellites, known as Lisa, that could detect the gravitational waves from colliding black holes. It would be best if they could be flown at the same time to study comic events in tandem. The money promised at this council should now make this possible.

Space transportation – In recent times, it has been arguments of the future development over Europe’s rockets that have bedevilled Esa ministerial meetings. Not this time. Differences of opinion on how to finish, financially support and further innovate the new vehicles known as Ariane 6 and Vega C were settled on the eve of the meeting. France, Germany and Italy dominate this programme area which will be receiving €2.2bn from the new budget. In the plan is an Italian-led project to launch a reusable mini robotic shuttle called Space Rider. It will carry experimental payloads into orbit and back. A first certification flight will take place in 2022.

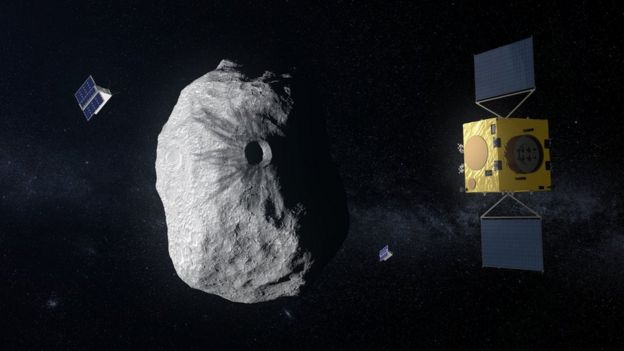

Space safety and security – This area, worth just over €540m, is all about protection – of space infrastructure and of Earth itself. Put before ministers was a satellite concept known as Lagrange that would stare at the Sun to warn of outbursts that could damage other spacecraft and interfere with radio communications and power grids on Earth. It’s a project primarily of interest to the UK. It didn’t receive all the money it needed and a decision was taken to work only on the spacecraft’s instrument for now. At the last ministerial council, member states rejected an asteroid encounter mission. The decision drew criticism because of our need to study objects that could hit – and devastate – the Earth. In response, Esa designed a new mission for subscription called Hera, and this time it won the financial support needed to proceed. Hera will visit a space rock that has previously been bombarded by a Nasa mission to learn more about how threatening asteroids could be deflected.