EDUCATION CONUNDRUMS

BRIDGING THE GENDER GAP

Gloria Spittel laments the low level of female participation in local graduate studies

The state of women in Sri Lanka could be likened to a superbly written yet nonsensical work of fiction. It has all the trappings of being an enjoyable read: fantastic access to healthcare, education, ownership and boastful moments of triumph (such as the forever accolade of the world’s first female political leader). But much like any novel, it has some confusing plot twists, which while not adding depth cast a shadow on the story.

Female tertiary education is not an ugly plot twist but makes for a rather confusing read. The numbers are high – higher than male enrolment across all state universities and institutes, and many streams of study at the undergraduate level. But this anomaly of greater female participation, which is evident in many activities in Sri Lanka, tapers off at the postgraduate and doctoral levels.

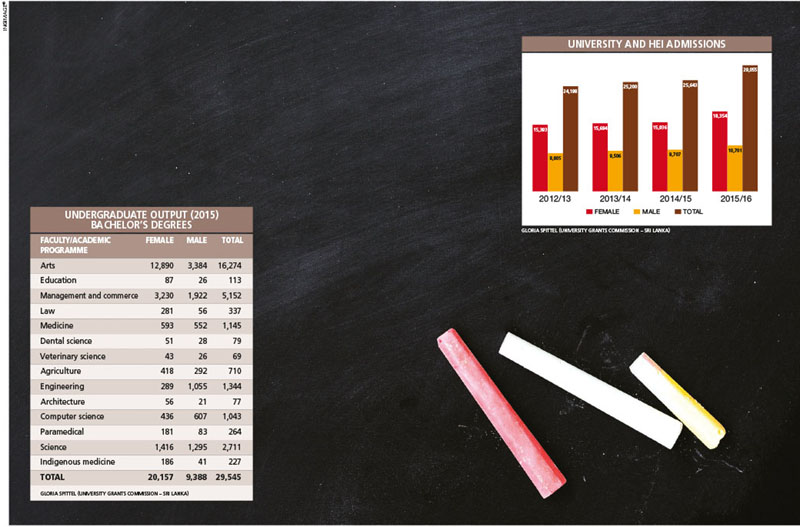

STUDENT ADMISSIONS According to the University Grants Commission (UGC), of the 155,550 individuals who were eligible for entrance to a state university or higher educational institute (HEI) in 2016 at the undergraduate level, a resounding 100,759 were females.

Only 18.7 percent of the total eligible population and 18.2 percent of eligible females were admitted to a university or an HEI. For the 2016 cohort however, female admission as a share of the total population admitted to a university or an HEI stood at 63.2 percent.

Female enrolment has stood at 62-63 percent of the cohorts admitted since 2012/13. It can be casually argued that these figures of qualification and admission to universities and HEIs display a tendency for females in Sri Lanka to excel in merit based systems.

On the other hand, higher female qualifications and enrolment in tertiary education could be a factor of male engagement in Sri Lanka’s military and a by-product of the civil war.

CULTURAL PRESSURES The pursuit of tertiary education amongst females is not deterred by the ‘culture’ of ragging or high possibility of sexual and gender based violence. In studies conducted on sexual and gender based violence at universities and HEIs, researchers have found that more female students are at the receiving end of abuse.

For example, a study conducted amongst 250 medical students at the University of Colombo in 2006 revealed that of the 55.6 percent of students reporting gender based violence, 72.2 percent were females. The forms of violence faced by students ranged from the physical, sexual and verbal, to psychological and emotional. The study also found that the perpetrators of such violence included faculty and non-faculty staff.

In another study undertaken in 2011, amongst 283 unmarried female undergraduates from the faculties of arts, science and law at a Sri Lankan university, 36 percent of respondents said they knew of female students that were coerced or forced to begin a romantic relationship. And a disturbing 73 percent of respondents suggested they knew of instances where females were forced to continue a romantic relationship.

A fear of physical harassment by male counterparts and social unacceptability were commonly cited as reasons for continuing or commencing a relationship under coercion.

LABOUR DYNAMICS Furthermore, even with the influx of female graduates (of the total graduates with bachelor’s degrees in 2015, 68.2% were females) in the market, female labour force participation in the first quarter of 2017 was estimated at only 37.6 percent.

The number of women employed in the 20-24, 25-29, 30-34 and 35-39 age categories all remain below 50 percent (at 43.6%, 42.3%, 48.6% and 48.2% respectively). In comparison, male employment for the same age groups stood at 74.3 percent, 94.4 percent, 95.7 percent and 96 percent respectively.

Female employment peaks in the 45-49 age group (54.5%) and women represent a staggering 74.9 percent of the economically inactive population.

STUDENT ENROLMENT A curiosity in female higher education appears in academic programme enrolment.

Across universities and HEIs in 2015, total enrolment at the undergraduate level indicated a disproportionate number of females in arts programmes, paramedical studies, management and commerce, and indigenous medicine.

Female enrolment in medicine and dental programmes was slightly higher than male enrolment. Males outnumbered females in engineering and architecture, law and science. And female student numbers were similar in computer science and IT programmes. At the postgraduate level however, female enrolment and graduation stood at 46.5 percent and 49.4 percent respectively.

The difficulties faced at the undergraduate level as outlined above coupled with external stressors – including societal and familial pressures towards marriage and childbearing – could factor against pursuing further higher education. However, the employability and employment opportunities afforded to females could be deterrents against further study too.

Unlike many of their counterparts in South Asia, females in Sri Lanka enjoy equal access to healthcare and education, have longer lifespans than their male counterparts and outnumber the male population. And more females than males are enrolled in government universities and HEIs. But they are under-represented in the economic and political spheres.

So the monumental question remains: what can be done to remedy this imbalance?

Leave a comment