DESIGNING FOR DISPLAY

ARCHITECTURE IN CONTEMPORARY EXHIBITION SPACES

BY Shahdia Jamaldeen

Given the progress and abstraction of contemporary art, Sri Lanka is no stranger to having a vibrant and thriving art environment. Amidst local artists receiving both national and international attention, and opportunities to connect across borders, it is imperative that we begin to provide spaces that are attuned to exhibiting artwork within the contemporary bounds of curation and arrangement.

Given the progress and abstraction of contemporary art, Sri Lanka is no stranger to having a vibrant and thriving art environment. Amidst local artists receiving both national and international attention, and opportunities to connect across borders, it is imperative that we begin to provide spaces that are attuned to exhibiting artwork within the contemporary bounds of curation and arrangement.

However, it was not until the 1990s that commercial art galleries, curators and dealers penetrated Sri Lanka (Tennekoon, 2020).

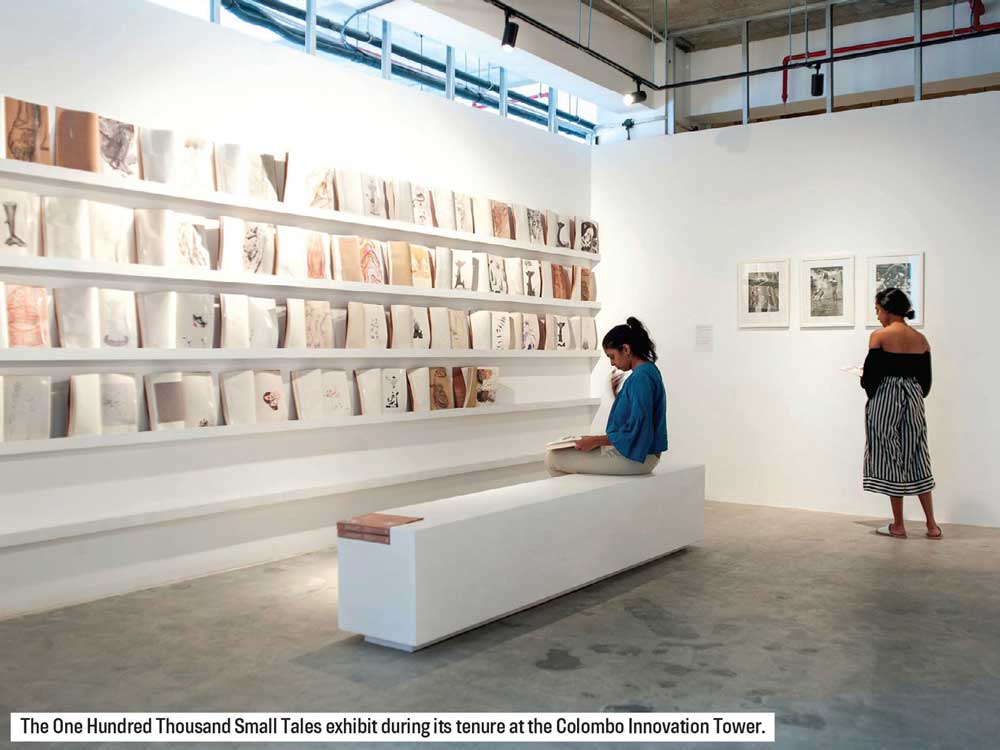

The Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) opened its doors in December 2019 with ‘One Hundred Thousand Small Tales’ compiled by Chief Curator Sharmini Pereira on the 17th floor of the Colombo Innovation Tower (CIT).

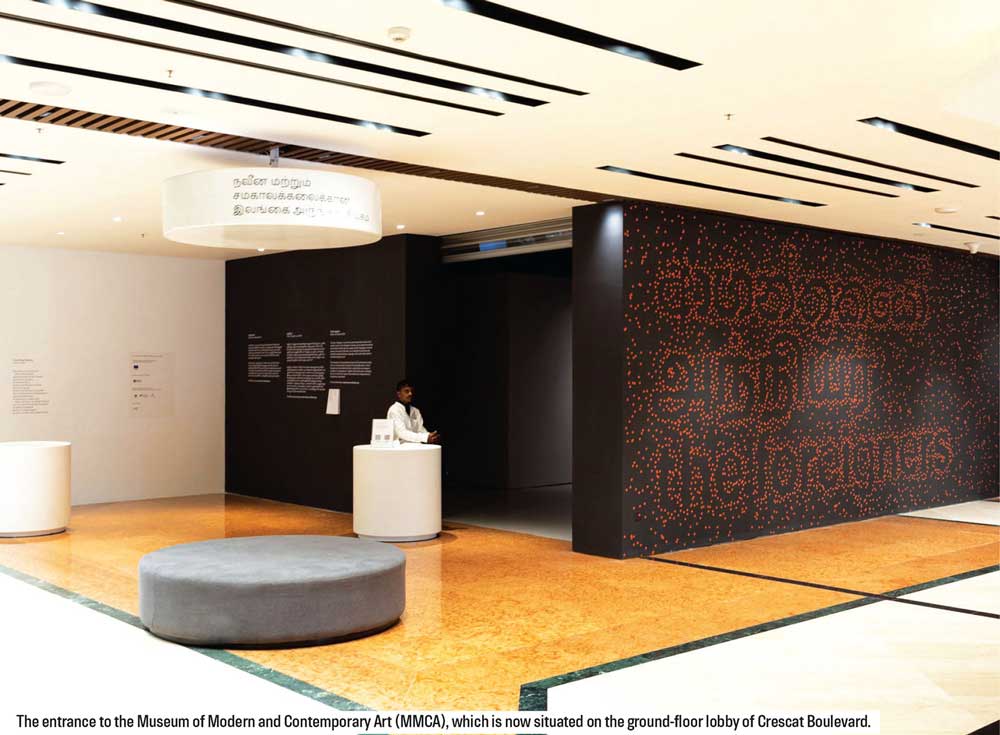

As the first modern and contemporary art museum in Sri Lanka, it is without doubt an important and landmark establishment. Within the standard stereotypical views most have on local museums, MMCA stands out for its transient qualities – both in its housing and artwork rotations (as the museum is now nestled in the public confines of Crescat Boulevard), and contemporary spatial design (Tennekoon, 2020).

The physical space of exhibition display is fraught with architectural language and rules that may seem simple but help to provide holistic experiences for any type of audience that enters.

Jonathan Edward, a promising young Architect who has been involved with the spatial design for MMCA in Colombo, explains the intimate relationship that the role of the architect plays in conjunction with the curator’s vision and plan for each rotation of artwork.

“The design process always begins as a response to the curatorial prospectus and narrative put forward by the curators. This provides me with an understanding of the story, the chapters within this story divided into sections and subsections, as well as the scales, formats and mediums of the works to be displayed,” he says.

Edward continues: “This develops into a dialogue where we look at how the narrative fits into the space in terms of zones/chapters and varying visual relationships. Do works sit across from each other or next to each other and so on?”

This outlines a clear connection between functional space planning, and the story of the artworks and running theme – meaning that the architects themselves must have a good understanding of the narrative behind the displayed collections.

This outlines a clear connection between functional space planning, and the story of the artworks and running theme – meaning that the architects themselves must have a good understanding of the narrative behind the displayed collections.

Like any art-based museum, the brief of spaces is mostly the same – a public access exhibition space, controlled storage, archives and administration areas.

Compared to CIT, Crescat Boulevard offers some positives such as less natural sunlight, which is highly important considering the value and nature of the artwork housed, as well as a steady stream of curious audiences due to the public nature of the mall, making such a space both inclusionary and accessible.

Unlike most formal museums in Sri Lanka, MMCA regularly converts its open spaces by hosting public workshops, tours, demonstrations and talks.

Exhibition spaces pose the interesting question of whether the space must be considered merely a container or part of the content as well (Coutinho and Tostões, 2020). Edward states that as the designer, his goal is to provide the simplest backdrop to allow the work on display to have maximum impact in tandem with curators Pereira’s and Sandev Handy’s collective ideations.

His conceptualisation follows questions regarding what the artist is trying to communicate, and if the design solution allows for it to shine through or disrupts the narrative.

Typically, the solution boils down to both design and material selection. The current exhibition at the MMCA titled ‘The Foreigners’ makes use of colour as its primary guidance.

“This was developed based on the large amount of projected video works on display that required less ambient light,” Edward notes, explaining: “Dark grey perimeter walls are offset by a light grey central ‘foreign object.’ These walls become the backdrop for the works on display. They are neutral and allow the works to do all the talking.”

“However, we do use pops of signal orange throughout the exhibition to grab visitors’ attention and direct them through the exhibition. These orange elements never come into contact with the works themselves,” he adds.

“However, we do use pops of signal orange throughout the exhibition to grab visitors’ attention and direct them through the exhibition. These orange elements never come into contact with the works themselves,” he adds.

Edward notes that the signal orange colour is particularly tied to this current theme, which deals with aspects of migration and exodus. Orange, he says, signifies movement akin to traffic cones, life jackets and rescue boats, and therefore, strategically plays the role of a signal within significant points of the exhibition space.

In addition to colour, other sensorial elements such as light, shadow and sound play important roles as well. The large number of video projections meant that the lighting needed to be controlled with darker perimeter walls being used to control the amount of light bounced and reflected.

MMCA’s previous exhibition ‘Encounters,’ which was also designed by Edward alongside Studio M’s Emile Molin, was a large showcase broken into three rotations. The challenge to present all three within a similar design language that was also unique to each one was tackled using simple architectural strategies.

“One such strategy was to raise elements off the ground. A shadow line was introduced where the walls met the floor; vitrines and shelves were cantilevered; and platforms, ottomans and visitor desks also appeared to float thanks to the kicks that were introduced,” Edward states.

He says: “The first rotation opened to the public as a pristine white space and the second rotation flipped this with the addition of a dark gallery completely covered with artwork. The third rotation returned to white.”

In an increasingly digital world, such physical spaces with tangible content continue to hold relevance in the public arena. Assistant Curator Education and Public Programmes Pramodha Weerasekera, who runs a consistent stream of public workshops and knowledge sharing sessions at the museum, affirms this: “I believe the merits lie in the activation of the exhibition and thereby, the space.”

“As a curator in the visual arts who works closely with audience engagement and education in a context such as Sri Lanka, I have been able to research and observe how valuable physical displays and spaces are for schools and universities in particular,” she explains.

“As a curator in the visual arts who works closely with audience engagement and education in a context such as Sri Lanka, I have been able to research and observe how valuable physical displays and spaces are for schools and universities in particular,” she explains.

Weerasekera says: “The space in a way acts as an incubator of knowledge as opposed to a mere white cube. Even the simplest act of looking at an artwork becomes an experience of learning especially in a space like MMCA.”

While exhibition typology is not wholly recognised in Sri Lanka, it has begun to make its mark in relevance both locally and globally.

To this end, Edward observes: “Making art accessible is critical in this day and age, and exhibition design helps facilitate these interactions and dialogues. The work of MMCA not only serves as a platform that celebrates Sri Lankan art and artists, but is also a testimony to the power of design in creating impactful, inclusive and accessible spaces.”

Following the current exhibition, MMCA will display its next collection, which is based on the works of Architect Minette De Silva in October 2023.

IMAGES Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

REFERENCES

Coutinho, B. dos S., & Tostões, A. (2020). The Role of Architecture in an Engaging and Meaningful Experience of the Physical Exhibition. VISUAL SPACES OF CHANGE: DESIGNING INTERIORITY – SHELTER, SHAPE, PLACE, ATMOSPHERE, 5(1), 11-13. https://www.sophiajournal.net/sophia-5-the-role-of-architecture-for-an-exhibition-engaging-and-meaningful-aesthetic-experience

Tennekoon, P. (2020). One Small Tale: Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Sri Lanka [An Introduction]. Museum and the Photograph.