COVER STORY

LMD EXCLUSIVE

LEVERAGING OUR CORE STRENGTHS

Bingumal Thewarathanthri assesses the role of the local banking sector in an economic revival and highlights the need to identify Sri Lanka’s core strengths

Following his appointment as the CEO of Standard Chartered Bank in Sri Lanka on 1 January 2019, Bingumal Thewarathanthri stands out as being the first Sri Lankan to serve in the role throughout the bank’s history in this country, which dates back over a century.

Following his appointment as the CEO of Standard Chartered Bank in Sri Lanka on 1 January 2019, Bingumal Thewarathanthri stands out as being the first Sri Lankan to serve in the role throughout the bank’s history in this country, which dates back over a century.

Having joined the bank in 2004, he counts more than two decades’ experience in the banking and finance sphere, holding several leadership positions in Sri Lanka and Africa.

Following the presentation of Budget 2021 in November last year, Thewarathanthri stated that the banking sector must play a role in boosting confidence in the market, “repurposing financial instruments to suit the unique needs of the economy and innovate more holistic value propositions to respond to differing circumstances.”

He stressed: “With the government flagging the national need to change the Sri Lankan mindset to a production-based economy that supports exports and domestic production capabilities with less imports, the onus is on the banks to assist the government to kick-start the economy, for businesses to thrive and the nation to progress.”

In this exclusive interview with LMD, he assesses the performance of Sri Lanka’s banking sector in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and its role in supporting an economic revival, as well as the importance of non-financial banking institutions in the ecosystem of finance.

Moreover, Thewarathanthri emphasises the importance of policy consistency and stability in transforming Sri Lanka from a debt-based economy to one driven by investment.

– LMD

Q:What is your assessment of the banking sector’s performance since the outbreak of the pandemic in both the local and global contexts?

A: When the pandemic emerged, local banks were still recovering from the aftermath of the Easter Sunday attacks in 2019. As such, it was a second wave of sorts for the sector.

However, together with the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL), the sector embarked on many initiatives to service its client base. This included offering moratoriums and introducing the Saubagya COVID-19 Renaissance Facility to support certain industries with working capital loans.

We at Standard Chartered used o ur own global US$ 1 billion fund to finance clients who shifted their manufacturing to combat the pandemic – i.e. organisations manufacturing personal protective equipment (PPE), face masks and so on. These loans were priced at cost.

ur own global US$ 1 billion fund to finance clients who shifted their manufacturing to combat the pandemic – i.e. organisations manufacturing personal protective equipment (PPE), face masks and so on. These loans were priced at cost.

While many industries seem to have recovered, tourism remains an unanswered question as it’s awaiting an influx of tourists. With the opening of the Bandaranaike International Airport (BIA), the landscape appears to be better than in the last quarter of 2020 but real inflows are not expected until the fourth quarter of this year.

Until then, the banking system will experience stress.

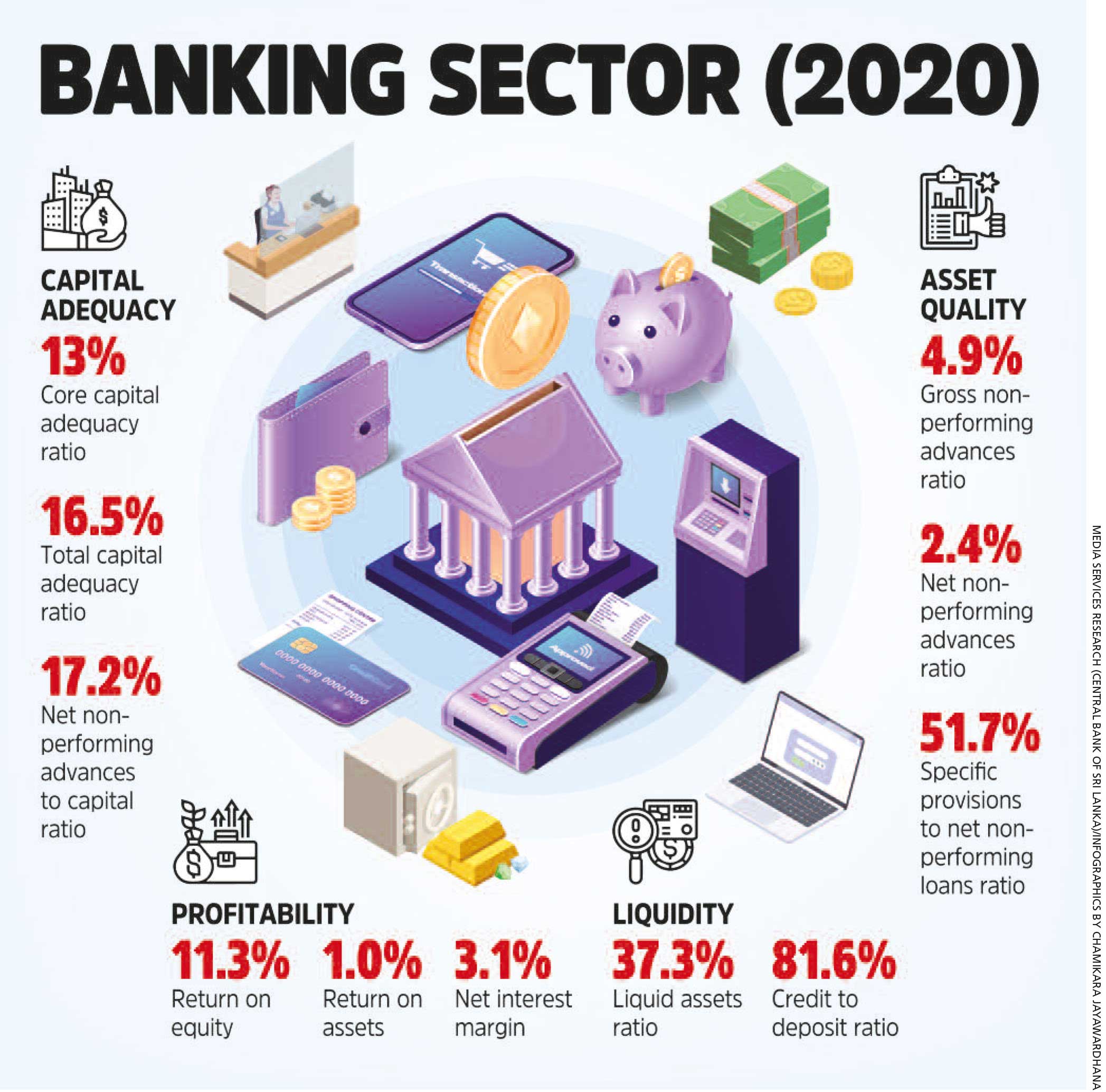

In terms of stability however, the local sector is performing well with returns registering double digits, the liquidity coverage ratio exceeding 190 percent and adequate levels of capital.

Global banks have suffered due to the pandemic, depending on their exposure to certain industries and markets. Valuations have reduced by 30-40 percent while returns on tangible equity (ROTE) fell from double to mid-single digits.

This is a drastic reduction – solely because of the expected credit loss recorded in keeping with IFRS 9.

Presently, the entire banking system is stressed as everyone is on the path to recovery. Regulators have played their part to increase liquidity to Rs. 175 billion and reduce the capital conservation buffer by up to 100 basis points, and control nonessential expenses as well as dividend payments.

Q: And what role must local banks continue to play in the country’s economic revival?

Q: And what role must local banks continue to play in the country’s economic revival?

A: Banks need to be patient – this is true for the local and global sectors. This year too will be challenging as economies are not out of the woods yet. The post-pandemic era will be much more difficult for some industries.

We will have to extend support for a longer period to help clients navigate challenges in the new world. We must ensure that the ecosystem is stable for us to bounce back as a community. But banks cannot do this alone – clients must meet them halfway by divesting some non-strategic businesses and pursuing leaner operations.

When it comes to SMEs, we have a role to play and should increase our participation. Most local banks have done well in this aspect. What’s missing is clean lending to the sector and using data analytics to evaluate client behaviour.

Q: How is the banking sector tackling challenges in the operating environment such as deteriorating asset quality and rising non-performing loans?

A: The sector is working closely with clients to provide guidance in restructuring to help them navigate through the crisis. While efforts are focussed on managing toxic assets, additional financing is being provided in other areas to help these businesses continue their operations.

In absolute terms, non-performing loans have increased but as a result of the moratoriums, we don’t see the real picture. Therefore, it is critical that we establish a plan for a reasonable transition from moratoriums to ‘business as usual.’ Industry non-performing advances (NPAs) have stabilised below five percent, and aside from restructured loans and pawning, other products are displaying early signs of recovery.

It must be understood that this pandemic is a once in a century occurrence. Therefore, despite the deteriorating asset quality, the sector has to extend moratoriums and support in other forms to help industries through the crisis.

Q:Is the local banking sector embracing global trends to remain relevant in the ‘new normal’ and address growing customer expectations?

A: In my view, local banks have performed well with some launching mobile apps, others pursuing digital onboarding strategies while everyone is driving digital payments.

How long these changes will remain is another question – Ibelieve that some advancements are here to stay but some customers still prefer to conduct transactions in branches.

In a post-pandemic environment, the world is unlikely to revert to how it operated in 2019. The regulatory landscape is expected to change dramatically in this era, similar to the period following the global financial crisis.

While I’m not certain if local banks are embracing new ways of working (i.e. working from home, and flexi and parttime work), they are surely ahead in terms of digital adoption.

At Standard Chartered, we believe that the world will not look the same following the pandemic.

We’re looking at ‘new Ways of Working’ (nWOW) where we focus on staying close to clients and home. As a result, we have observed an increase in productivity and efficiency. Sri Lanka is set to adopt nWOW by the third quarter of this year.

Q: What reforms are needed in the Banking Act to strengthen Sri Lanka’s financial system and protect it from future external shocks?

A: The pandemic was not only an external shock – the entire world was in shock. The impacts were not solely dependent on exposure to a particular market.

Export markets were losing demand, supply chains shifted from just in time to just in case inventories and the domestic market was impacted by lockdowns, which we hadn’t experienced before.

To manage such situations better in the future, we should create a large domestic economy with local production and less dependence on the external sector. To this end, creating development banks that can support new projects will be critical. It’s also important to divert lending to important sectors through clear policies.

We have also observed that countries with higher revenue to GDP ratios did well in terms of fiscal stimuli. Sri Lanka’s revenue has been a constant challenge but the answer is not increasing taxes haphazardly. The country will need to implement serious reforms to broaden its tax base.

This is a major challenge and an opportunity for the government.

In cases of shocks, there should be provisions to create a bad bank and facilitate the securitisation of toxic portfolios. Although we agree that collateral should not be liquidated during a pandemic, more leeway on bringing borrowers to the negotiating table will be crucial to reviving the economy in a post-pandemic environment.

Q: Do you believe  that there is a need to introduce a legal framework to regulate non-banking financial institutions (NBFIs)?

that there is a need to introduce a legal framework to regulate non-banking financial institutions (NBFIs)?

A: Certainly – the Central Bank has a framework for this. This sector is governed by the Director of Supervision for Non-Bank Financial Institutions (SNBFI).

Having said that, we must ask if there is a need for 48 NBFIs. If so, how do we govern them?

My view is that the banking sector cannot do what these institutions do – so both are needed in the financial system.

However, since these NBFIs also engage in many banking activities, there is a need for regulation similar to that for the banking sector – especially as some are larger than banks.

Q: As the Central Bank of Sri Lanka looks to pursue the consolidation of the financial services industry, what measures are needed to ensure that all customer segments continue to be served to their satisfaction?

A: There isn’t a perfect model. Markets such as India offer priority lending for agriculture, SMEs and strategic initiatives. We must look at what we’re hoping to achieve; if Sri Lanka is to be an export led economy, it must emphasise every type of export that we are capable of.

In this environment, merging NBFIs and banks would not make sense as the former would lose their purpose. Some banks will not engage in certain sectors – microfinancing and leasing machinery among others.

Given this scenario, there should be a model where banks play to their strengths without trying to do everything with every bank or NBFI. For example, global banks would do well by taking care of correspondent banking and cross border receivable services with limited participation in the microfinance sector.

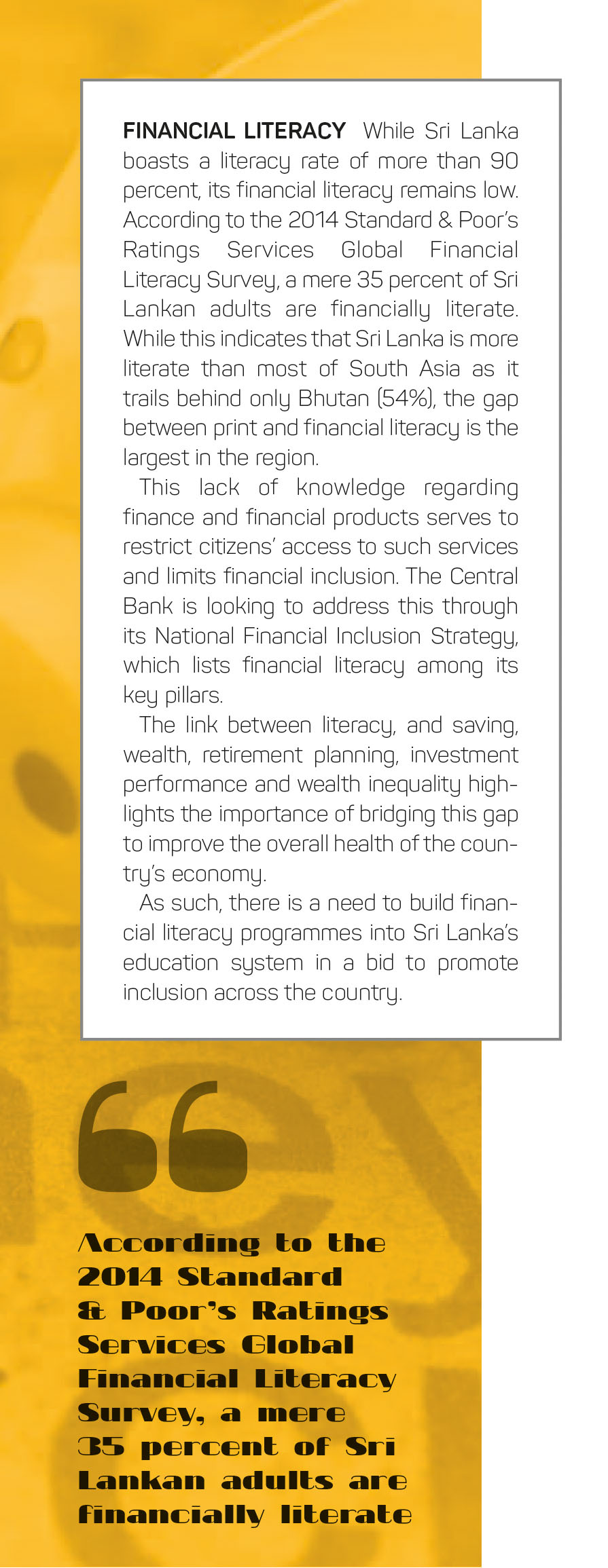

In terms of financial inclusion, we rank well among emerging markets with over 70 percent of the population maintaining bank accounts. The issue is the level of financing for lower income sectors, which still pay substantial sums to loan sharks and shadow banks.

At Standard Chartered, we have taken a stand to increase our SME participation. This will be driven through partners of our own clients and available digital partnerships, to help SMEs that think global and require a bank with a global footprint. We are ready to support them across Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

Q: Are the Sri Lankan Sustainable Banking Principles (SBP) geared to support the country’s growth in the prevailing economic landscape?

A: According to Standard Chartered’s ‘The $50 Trillion Question’ report, 20 percent of the world’s top 300 investment firms with total assets under management of more than US$ 50 trillion are not aware of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). About 13 percent linked funds to the goals while only five percent offered green bonds.

This research also indicates that sustainable financing opportunities in Sri Lanka amount to about 16 billion dollars, which entails transforming brown industries into green businesses, predominantly in water distribution, power, data connectivity, education and healthcare.

In 2016, the Central Bank joined the IFC supported Sustainable Banking Network (SBN) with a view to promote sustainable finance in Sri Lanka. And in 2019, CBSL introduced a road map for sustainable finance, offering more clarity to the sector.

CBSL’s sustainable ba nking framework involves the participation of 18 Sri Lankan banks. However, there is a long way to go in terms of tapping the full potential. We believe that sustainable finance is the way forward for markets such as Sri Lanka to access global capital.

nking framework involves the participation of 18 Sri Lankan banks. However, there is a long way to go in terms of tapping the full potential. We believe that sustainable finance is the way forward for markets such as Sri Lanka to access global capital.

In terms of battling climate change, supporting brown industries in emerging markets makes more sense compared to OECD markets since they have a larger positive impact when going green.

Q: Is the prevailing monetary policy in the country stimulating the economy while tackling longstanding economic imbalances such as the balance of payments situation?

A: Sri Lanka took the stance of increasing the fiscal deficit above 10 percent solely to support industries during the pandemic. The fiscal stimulus entailed diverting funds into projects, and activating construction and a few other industries. Sri Lanka does not have a great deal of foreign reserves so the government prudently implemented import controls, enabling the country to conclude last year with a current account deficit of US$ 1.1 billion.

However, this is a short to medium term solution.

The Central Bank has taken several measures to stimulate the economy by reducing interest rates, increasing liquidity in the banking system, and pushing banks to lend and offer low interest housing loans.

As a result, we see many industries – except tourism – bouncing back with some performing better in 2020 than in any other year. The white goods sector is an example of this.

Q: Fitch Ratings has said that the downgrading of Sri Lanka’s sovereign rating to ‘CCC’ in December will impede local banks’ ability to raise foreign funds for lending purposes. What is your take of this assessment?

A: In my opinion, the ability to raise foreign funds will largely depend on the strength of individual entities and the cost they are willing to pay while the country risk would limit the overall appetite.

Presently, local banks have credit lines from global banking institutions and bilateral agencies when it comes to dollar funding, which is sufficient to address our current needs. We have also observed a couple of development finance institutions (DFIs) lending to local banks as well as corporates over the last six months.

Following the recent currency swap deal with China, the situation has improved – this can be seen in the tightening of Sri Lanka’s sovereign bond yields. Additionally, the China Development Bank (CDB) loan of 700 million dollars is almost finalised and we believe that Sri Lanka could benefit from the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) programme as well.

With all this, the country will have enough breathing room to navigate until tourism bounces back and we witness a steady flow of foreign direct investments (FDIs). Tourism was earning US$ 3.6 billion before the pandemic and we believe we’re ready to recover at least a billion dollars this year.

Q: How do you view the value of the Sri Lankan Rupee and the Central Bank’s efforts to manage the exchange rate? And where do you see the rupee heading in the medium term?

A: Depreciation between five and seven percent is expected in any emerging market currency.

When there is substantial foreign debt to service, management of the exchange rate becomes far more important. Against this backdrop, CBSL has played a major role. Among the measures it has taken are restricting forward contracts, converting 25 percent of export proceeds, implementing import controls and issuing letters of credit (LCs) of 180 days for essential imports.

In a very difficult year with rising oil prices, there is pressure on Sri Lanka’s import bill. However, CBSL managed to keep the exchange rate below Rs. 200 in the first quarter of this year, which is outstanding.

With increased demand in a post-pandemic environment and pressure on oil, the currency depreciating further in the near future is inevitable.

Q: Are you confident that Sri Lanka can meet its debt repayment obligations this year and the next? And what sensitivities are there?

A: Yes – Sri Lanka’s foreign reserves amounted to US$ 4.6 billion at the end of February while its obligation for the rest of the year is 3.5 billion dollars. The US$ 1 billion sovereign bond (ISB) is the most critical and will be settled in July.

I believe some of these debts will be rolled over. Reserves could also be used for this while reducing the import cover to about three months or the swap from China could be used if necessary.

Furthermore, export revenue is expected to increase to 13 billion dollars this year while workers’ remittances could grow to about US$ 8 billion. Meanwhile, the import bill could be managed at around 1.4 billion dollars a month.

As the government is looking to avoid adding to our foreign debt, it could work with bilateral and multilateral agencies to roll over some of these debts to manage short-term shocks.

Sri Lanka has taken a much more honourable route by restricting its own imports and managing within these boundaries. We are absolutely confident about this year’s debt settlements due to the measures taken.

However, we have US$ 4 billion of debts each year until 2025. The success of tourism, FDI and exports will be vital for Sri Lanka to move forward.

Q: What measures are needed to ensure that Sri Lanka shifts from a debt driven economy to an investment economy?

Q: What measures are needed to ensure that Sri Lanka shifts from a debt driven economy to an investment economy?

A: Many economies have debt to GDP ratios hovering near 100 percent but they borrow at cheap prices and don’t have rollover risks. As Sri Lanka will not be able to do so, it’s critical that we pursue an investment plan, and attract FDI and improve our reserves.

To do this, we need stability and consistency; while we have the former, the latter is needed in terms of policies – strategic pillars should not change with changes in the government.

We must understand what Sri Lanka needs as a country and its core strengths. How do we leverage and build an economy around them?

Once we decide on a path, a catalyst is needed. For example, Vietnam’s catalyst was a white goods manufacturer from South Korea that decided to invest due to a trade treaty between the Southeast Asian nation and the US. This changed the investment climate of the country drastically.

The Sri Lankan government has come up with consistent tax policies for certain sectors and the Port City legislation is almost ready. What we need is more rapid execution and to be open to partnerships without trying to do everything on our own.

– Compiled by Lourdes Abeyeratne