COUNTRIES AGREE TO PLAN MINIMUM CORPORATE TAX AROUND THE WORLD

World Economic Forum

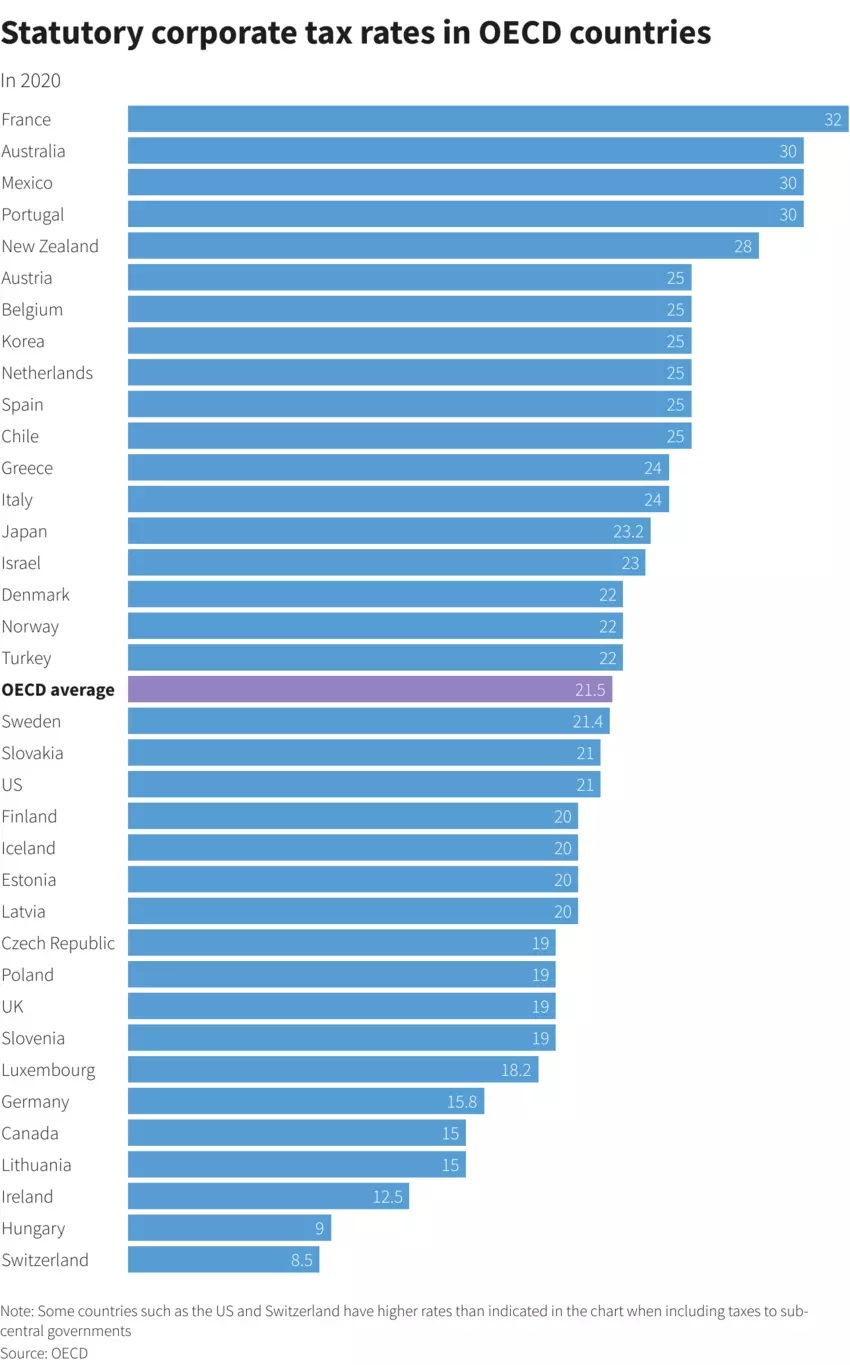

- A plan brokered by the OECD has been announced for countries accounting for 90% of the global economy to set a minimum corporate tax rate of 15% across the world.

- Only 4 out of the 140 countries participating in the talks did not wish to participate in this plan.

- The new rules would narrow the gap between the countries with the highest and lowest tax rates.

- However, it has faced some controversy, since critics believe the multilateralism of the deal should extend further.

Countries accounting for 90% of the global economy hammered out an agreement to set a minimum corporate tax rate across the world. The deal’s minimum 15% corporate tax rate represents years of stop-and-start negotiations to deter multinationals from relocating to tax havens.

The plan, which was brokered by the OECD and announced on Oct. 8, is far from a done deal. Many technical and political details still need to be sorted out, not least the approval of the US Congress. Still, the fact that it happened at all reveals the return of a more cooperative climate after the Trump administration’s “America First” approach. Only four out of the 140 countries participating in the talks—Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka—bowed out.

The new rules would counteract some of the effects of what policymakers call “the race to the bottom” in corporate taxes across the world by narrowing the gap between the countries with the highest and lowest rates.

US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen called the deal “a once-in-a-generation accomplishment for economic diplomacy.” Irish finance minister Pascal Donohoe, who was a holdout until the last minute, said the agreement “demonstrates the importance of working together to achieve positive outcomes for the world.”

Global minimum tax stalls under Trump

Talks to revamp the global tax system have stretched over years. Last summer, the Trump administration walked away from the negotiating table over a disagreement of how to tax US tech giants like Apple and Google. European companies wanted them to pay more through new “digital taxes.” In response, the US, threatened to impose tariffs on European goods.

The US rejoined the global discussion under Joe Biden, whose administration was more open to increasing taxes on US multinationals in order to secure a strong commitment to a minimum global tax. Under the new agreement, the world’s biggest corporations will have to pay taxes in countries where they do business, even if they don’t have a physical presence there.

Trade disputes averted

The diplomatic accomplishments go beyond the new global tax. Because the deal settles the fight over tech company taxes, both sides can hold off on retaliatory measures. “Absent this type of agreement, there were likely going to be an increasing number of tax disputes that spilled into trade disputes,” said Daniel Bunn, vice president of global projects at the Tax Foundation, a Washington DC-based think tank.

What’s the World Economic Forum doing about tax?

Critics say the deal’s multilateralism doesn’t go far enough, arguing the tax rate floor needs to be higher to fairly spread the benefits of the proposed changes. As it stands, they say, wealthy countries will benefit the most. “Everyone else has been left out—especially lower-income countries which lose the greatest share of their current tax revenues to corporate tax abuse,” said Alex Cobham, chief executive at advocacy group Tax Justice Network, in a statement.