CORPORATE SUSTAINABILITY

ORGANISATIONAL PARADOX

Kiran Dhanapala describes the benefits and burdens of sustainability

Sustainability professionals often become frustrated at the lack of progress in advancing their cause within the organisations they represent. Many gains from sustainability don’t amount to having entered the mainstream. Worse still, the gains often become difficult to achieve after picking low-hanging fruit. This makes justifying resources to the non-converted or disinterested even harder.

Globally, sustainability has its paradoxes: on the one hand, there are exceptional champions such as Unilever’s Paul Polman; but on the other, they are a minority and not sufficiently widespread. Moreover, these champs seem to make little headway against the impact humans continue to have on their natural environment.

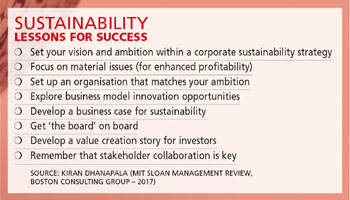

A study conducted by the MIT Sloan Management Review and Boston Consulting Group analysed annual global surveys of over 60,000 sustainability professionals from across sectors over eight years in 118 countries, which are supplemented by interviews.

They reveal two interesting trends: companies are more transparent in their sustainability activities; and companies and coalitions are working together, to develop new standards and goals for sustainable business practices.

Respondents acknowledge that a sustainability strategy is needed to be competitive and corporate sustainability is no longer marginal or loss-making. The study produces eight lessons. It reveals that the uptake of fundamentals needs strengthening, and we need to think more strategically and broadly about how we see sustainability – not in engineering or resource-efficiency terms (given the law of diminishing returns) but as reengineering a business.

This requires building and strengthening the understanding that sustainability is the new normal – and that it’s everyone’s business.

Short-termism or the ‘tragedy of the horizon’ refers to rigid return on investment (ROI) criteria for project approvals. Yet, much has been done to value environmental and social impacts. And social ROI (SROI) is increasingly used. It’s a broader concept of value including social and environmental improvements by incorporating social, environmental and economic costs and benefits. These methods will help justify projects and the allocation of scarce resources using objective tools.

Success in sustainability requires a long-term strategic vision and business model innovation – much more than CSR and LED light bulbs! It implies a meaningful sustainability strategy that connects its initiatives with issues and activities that are material to the business. For a bank, think beyond a LEED Platinum head office to analyse a loan portfolio for environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks, and stranded assets.

Patagonia recycled plastic waste into fabrics and encouraged customers to mend or repair clothing rather than buying new. It also contributes one percent of annual revenues to non-profit conservation organisations that resonate with its customers. This resulted in a compound annual revenue growth of 14 percent and a 300 percent spike in profits from 2008 to 2015. That’s what success looks like!

Focussing on material issues means 50 percent more profits from sustainability activities than not doing so. This is the value-add of sustainability.

Building a business case is essential. But it is often neglected with only 25 percent of companies having a clear business case for sustainability initiatives. This can also be achieved by creating coalitions to develop tools to help build a business case.

For example, Hilton did this with BSR in developing the Center for Sustainable Procurement (later the Procurement Leadership Group) in 2015. This led to innovations in supply chain sustainability that created business value, and positive impacts for Hilton and other members.

But beware of business cases that justify incremental investments based on ROI without changing their business model. Returns on resource efficiency are limited by diminishing returns.

Innovation in business models is also a game changer. The study notes that combinations of innovation in the value chain and target segments had the strongest impact on profits from sustainability. And this needs strategy, leadership and organisational change to deliver benefits.

Implementing a sustainability strategy implies managing through key performance indicators (KPIs) that are linked to goals and clear responsibilities. But the scope of this is limited unless middle management has been educated and engaged all along. The study reveals that only 31 percent of middle managers were familiar with corporate sustainability goals.

Change and awareness come only in communicating the bigger picture that senior management already recognises. For instance, Unilever began talking sustainability in the late 1990s, joining Oxfam in 2002 on the global Sustainable Food Lab network. Paul Polman was appointed CEO in 2012, long after implementing KPIs for every business unit.

Change took time. And the intelligent use of that time yielded benefits.