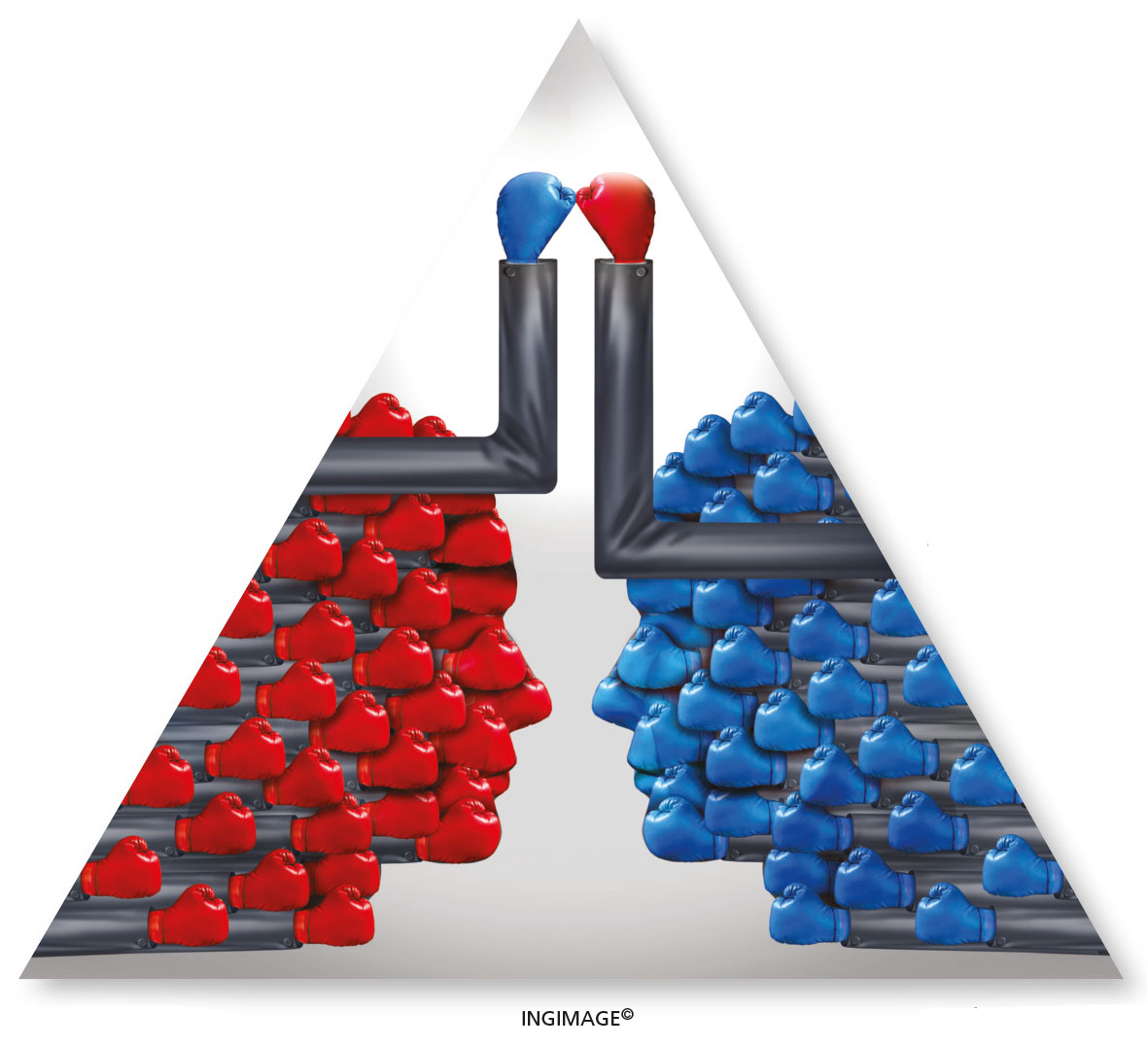

CO-OPETITION DYNAMICS

RIVALS IN COLLABORATION

Don’t rule out the value of ‘co-opetition’

BY Jayashantha Jayawardhana

The term ‘co-opetition’ refers to a mix of competition and cooperation or the practice of rivals collaborating. Today, this is common in a range of industries, being adopted by rivals such as Apple and Samsung, DHL and UPS, Ford and GM, and Google and Yahoo.

So why do businesses that appear to be rivals choose to collaborate?

Adam Brandenburger and Barry Nalebuff explain why in their Harvard Business Review (HBR) article headlined The Rules of Co-opetition.

They write: “There are many reasons for competitors to cooperate. At the simplest level, it can be a way to save costs and avoid duplication of effort. If a project is too big or too risky for one company to manage, collaboration may be the only option.”

“In other cases, one party is better at doing A while the other is better at B, and they can trade skills. And even if one party is better at A and the other has no better B to offer, it may still make sense to share A at the right price,” the writers add.

However, co-opetition raises important strategic questions. How will the competitive dynamics in your industry shift if you cooperate – or don’t? Will you be able to protect your most valuable assets?

This calls for scrutiny, analysis and evaluation.

So let’s explore the decision to cooperate with rivals.

Before rushing headlong into co-opetition, a business or brand has to carefully evaluate the competitive dynamics in play at the time in their market. Let’s illustrate this with an example from the real world of business.

Honest Tea, a business cofounded by Nalebuff, was approached by Safeway to make a private label line of organic teas for its supermarket. The new line would definitely eat into Honest Tea’s existing Safeway sales; and even though the supermarket was offering a good price, the deal would eventually not be profitable for Honest Tea.

But there was a catch.

If Honest Tea didn’t take up its offer, it wouldn’t be hard for Safeway to court another supplier such as Tazo Tea, which is a rival business. Honest Tea figured that if it agreed to the deal, it could design the new Safeway O Organics line to imitate the flavours and sweetness of Tazo products, and compete less against its own. If Honest Tea had turned Safeway down, Tazo would probably have said ‘yes’ and aimed at the former’s flavours, leading to the worst possible outcome. So Honest Tea did take up the offer.

Yet, Honest Tea declined a similar request from Whole Foods Market as the grocery chain wanted a clone of Moroccan Mint included in the private line. Since Moroccan Mint was its best-selling tea at the time, Honest Tea didn’t want to compete against itself and rightly believed that its rival would have trouble imitating the flavour.

These two instances clearly illustrate when to say ‘yes’ or decline any offers following a thorough evaluation of the competitive dynamics at work. Agreeing to the wrong offer can undermine one’s competitive strengths and hurt the business.

Sharing your secret recipe or competitive advantage with a rival is almost always a tough decision to make. Brandenburger and Nalebuff cite four specific instances of co-opetition. And almost every co-opetition deal falls into one of these categories.

Neither party has a special recipe at risk but their combined ingredients create value; both parties have a special recipe and sharing puts them both ahead of their common rivals; one party has a strong competitive advantage and sharing only heightens it – and even so, less powerful parties are willing to cooperate; or a party shares its secret recipe to reach another’s customer base even though doing so carries risks for both parties.

In the global smartphone market, although Apple and Samsung are rivals, they’re also famously engaged in co-opetition.

For instance, Samsung supplies Apple’s new Super Retina OLED ‘edge to edge’ screen for the iPhone X. In addition to being a major phone maker, Samsung is also a major supplier to manufacturers including Apple across several generations.

If Samsung had refused to supply, it could have temporarily hurt Apple sales in the high end smartphone market where Galaxy and iPhone compete. But then Apple could have readily turned to LG or BOE and reinforced the competitive position of Samsung’s screen technology rivals.

That apart, Apple is recognised for helping its suppliers enhance their quality. In the year before the iPhone X launch, nearly 30 percent of Samsung’s display business revenue (some US$ 5 billion) was generated from sales to Apple.

Despite their rivalry, both these players stand to gain from this collaboration thanks to Apple’s loyal customer base and Samsung’s world-class screen technology.

All of this means that collaborating with rivals isn’t something to simply rule out!