CLIMATE FINANCE

ECOLOGY FUNDS CONUNDRUM

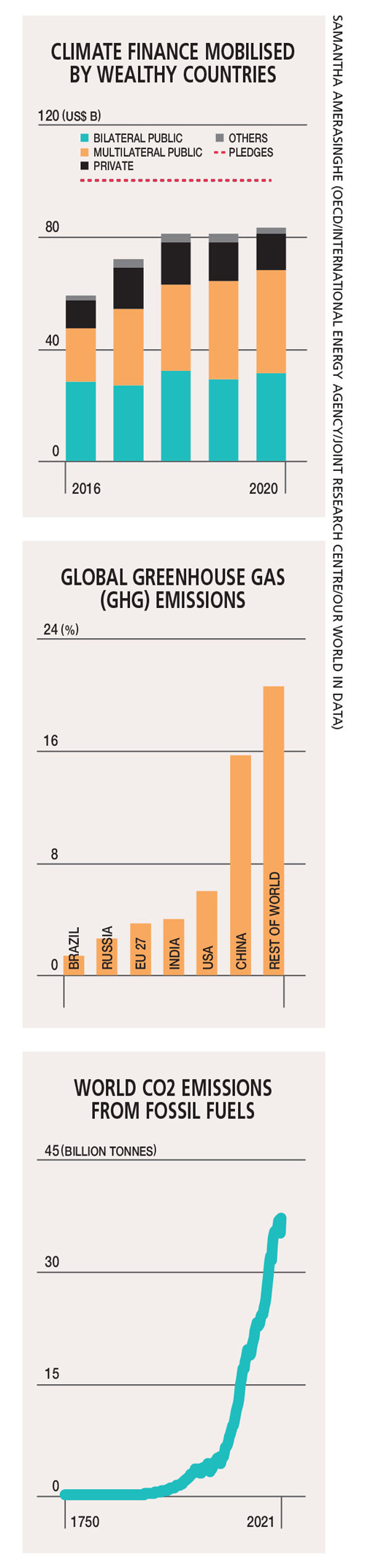

Samantha Amerasinghe highlights the shortfall in global financial contributions

High on the agenda at the 2023 UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP28) in Dubai, held in December, was the urgent need to increase climate finance and accelerate energy transition – even as the world continues to grapple with rising temperatures and more frequent catastrophic natural disasters.

Since COP21 in 2015, the UN’s annual climate conferences have revolved around how to implement the Paris Agreement, which aims to keep the global average temperature rise to well below 2°C and pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C above preindustrial levels; adapt to climate change and build resilience; and align finance flows with ‘a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions’ and climate resilient development.

The provision and mobilisation of climate finance is a key priority for many developing countries. They need financial resources, as well as technology transfers and capacity building, to help reduce emissions, adapt to climate change, and address loss and damage.

However, the failure to meet these ambitious targets in a timely manner from pledges made in the past has been a source of frustration for many developing countries.

It’s startling to note that by 2030, the developing world will need more than US$ 2.4 trillion annually from public and private sources to address climate change.

In 2009, developed countries pledged to mobilise 100 billion dollars every year from 2020 onwards – a small fraction of what is needed.

While it’s difficult to know what share needs to come from public coffers, most experts agree that US$ 100 billion in public funding won’t be sufficient to decarbonise the developing world. They predict more than double that may be required over the next decade although there’s no global consensus on the amount at this time.

Even though some progress has been made, and international climate finance has more than doubled – some say tripled – over this decade and a half, donor countries have repeatedly fallen short of the 100 billion dollar mark.

It’s worrisome that since this target was tough to meet, it had a negative impact on negotiations – given that this process relies on trust that governments will deliver on their promises.

At COP28, member states continued their negotiations on a new climate finance goal to replace the US$ 100 billion annual commitment. It’s imperative that finance from developed countries is scaled up.

The challenge now is how best to mobilise committed finance to restore trust. Most likely, COP28 served to kick the can down the road on a major new funding pledge such as agreeing that nations should commit to a fresh target in 2024 or 2025.

There are three main challenges to climate financing – viz. funding, institutional capacity and the lack of accountability mechanisms. Arguably, the chief challenge especially in low income countries is a lack of funding for climate projects.

Because governments don’t have enough money, countries will have to rely heavily on the private sector for funding climate initiatives.

Governments need to unleash the potential of the private sector by creating the right policy incentives and instruments.

Some contend that the way forward is to attract more equity financing from pension funds – or perhaps insurance businesses – as this is a better instrument than debt especially as foreign investors would be tied to projects for longer and it would shield developing economies from indebtedness.

Another concrete way that governments can empower the private sector is by shaping better functioning voluntary carbon markets. So far, these markets have been weighed down by quality and integrity issues.

Governments will need to increase trust in these markets by enforcing high integrity standards and robust regulations if they are to serve as powerful instruments for channelling private capital from developed to developing economies.

A further concern is that many poor countries lack the financial infrastructure needed. And this makes channelling substantial foreign investment into projects very challenging.

The lack of institutional capacity to facilitate the world’s climate finance needs is also a hurdle with many multilateral development banks (MDBs) not sufficiently focussed on handling climate risks due to a lack of relevant expertise in these institutions.

We need international financing institutions to operate more efficiently and MDBs should be substantially recapitalised.

Accountability mechanisms are also inadequate. Currently, there is no mechanism to hold governments and institutions accountable for meeting financing promises. Richer countries have often fallen short of their responsibilities to report investment estimates accurately.

Moreover, greenwashing is evident as ‘green funds’ are not required to disclose their carbon footprints or emissions output.

Money is waiting to be unlocked. Fixing the climate finance gap is doable but must begin with restoring trust. Raising climate ambitions and delivering on pledges is paramount, along with supporting fundamental reform of the global financial architecture to deliver climate finance at scale.

COP28 was crucial to ensuring that governments continue to build the right frameworks and political will to unlock this much needed money.

Leave a comment