CLIMATE CHANGE

HIGHWAY TO CLIMATE HELL?

Samantha Amerasinghe wonders if COP27 has honoured pledges made in Glasgow

Another year, another international climate forum and high expectations that progress will be made on the critical issues of global warming, carbon emissions and tackling climate change… This year’s meeting held in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, marked the 27th gathering of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – or COP27 for short.

COP27 reached a historic agreement (signed off by almost 200 countries) on a fund to compensate developing countries for loss and damage. This has been hailed as the most important climate advance since the Paris Agreement in 2015.

Following three decades of paying little attention to the demands of poor countries, rich nations finally seem to have come around to agreeing to pay poorer countries for the damage caused by climate change – and more pertinently, a warming world.

Rich countries, particularly the US, had long opposed a loss and damage fund fearing legal liability for years of churning out greenhouse gas emissions. This is a big win for poorer nations, which have long called for further funding because they often suffer the most extreme impacts of catastrophic climate events despite their small carbon footprints.

According to the agreement, the loss and damage fund will initially draw on contributions from developed countries, and other private and public sources such as international financial institutions.

It is an important positive step.

Nonetheless, climate talks are deemed by many to have fallen short as no further progress was made on emission reductions to keep the world at its 1.5°C temperature goal. UN climate scientists say that global emissions must be cut by 43 percent to maintain the world’s temperature at 1.5°C by the end of the decade.

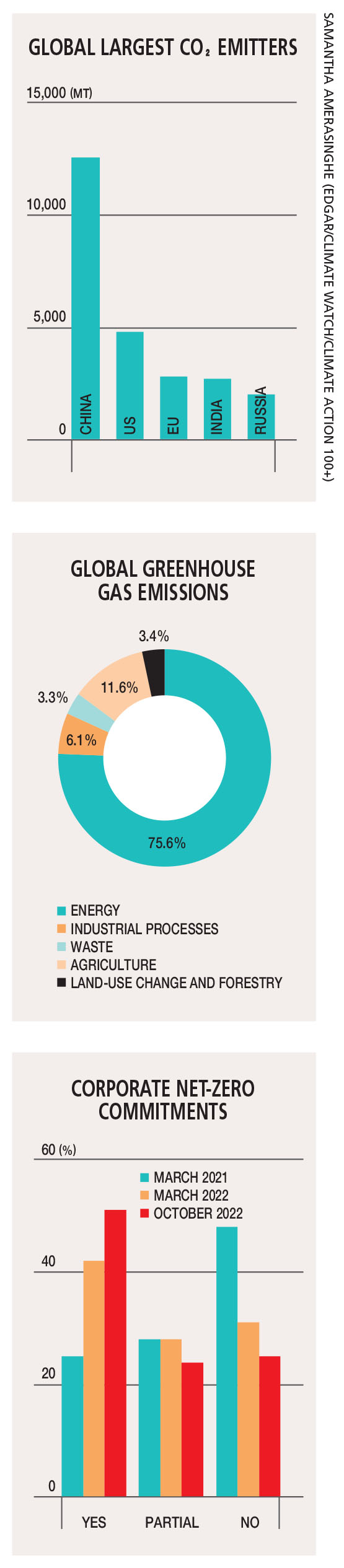

Instead, we have seen emissions rise one percent in 2021 (even more in the US) and are on course for a 10 percent increase this decade.

In contrast to COP26 in Glasgow, which was about setting timelines for ambitious climate goals, COP27 was more about implementation plans and making countries do what they say. However, there’s no clear commitment on safeguarding the outcomes secured in Glasgow and many gaps remain in the signed agreement.

In his keynote speech at the conference, President Joe Biden recommitted the US to its promise of cutting emissions by 50 percent by 2030 from its 2005 level. The EU and Indonesia. also came up with more aspirational goals.

That said, countries that are ready to act now are still a minority with only 29 from among 196 nations providing revised action plans.

Surprisingly, this was the first COP where agriculture took centre stage, given that food supply accounts for roughly a quarter of global emissions.

More sustainable fertiliser practices – together with lower emitting fertilisers – are key, as is the case with new technologies that turn animal emissions into energy. China, which accounts for a fifth of the world’s methane emissions, needs to be a leader on that front.

But the most contentious opportunity may be regenerative agriculture. This refers to a series of practices such as cover cropping and no-till farming, which will ensure that soil captures and sequesters greenhouse gases.

The United States is racing ahead with voluntary markets that will allow companies and investors to pay farmers for harnessing their soil in return for carbon credits.

Unfortunately, there weren’t any clear follow ups agreed upon on the phase down of coal or phasing out of fossil fuels. This was a major blow to many countries as the COP27 agreement simply repeated the prior meeting’s call to accelerate efforts to phase down unabated coal power and phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.

The formation of the Just Energy Transition (JET) partnership of wealthy nations and financial institutions to help developing countries wind down coal bodes well.

South Africa and Indonesia have signed on, and Vietnam may be next. But the enormous cost raises concerns about burdening poorer countries with more debt and the partnership is missing two of the world’s largest consumers of thermal coal – China (50%) and India (close to 20%).

Climate funding is also a huge concern, given the sharp rise in interest rates in 2022 – this has quietly become a drag on climate policies especially in developing countries. The concern even fuelled a COP meme: #WTF – as in ‘where’s the finance?’

One reason is a lack of sufficiently large projects. UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance Mark Carney believes the world needs projects to the tune of US$ 1 trillion annually to quadruple the ratio of renewable energy to nonrenewable investments to 4:1.

Leave a comment