CHINESE ECONOMY

SIGNS OF DISTRESS IN CHINA

Samantha Amerasinghe hopes for a moderate slowdown and impact on the world

China’s economy is clearly contracting sharply under the weight of its ‘zero COVID’ policy and generating a new wave of concerns about its economic future, as well as its position in the global economy.

Transitory politically motivated gains by China’s leaders have trounced long-term economic and political objectives in their fight against an improbable enemy – the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2.

The large selloff of Chinese assets and corporates’ reassessment of the importance of China in their global strategies reflect the shifting priorities of businesses navigating uncertain times. It also highlights the reality of China’s economic distress.

This month, we assess the global implications of slower growth in China.

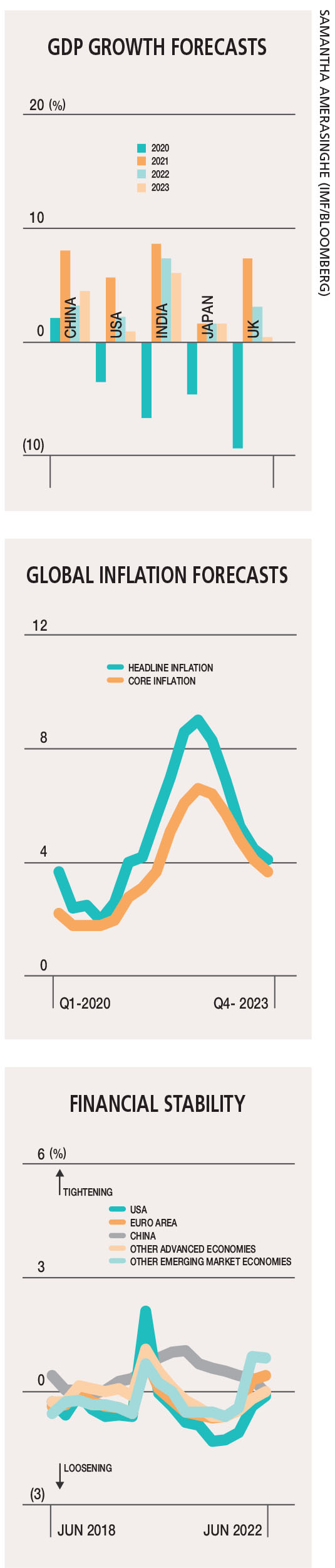

China’s Prime Minister Li Keqiang recently acknowledged that economic difficulties are greater to a certain extent than in the pandemic’s first phase in 2020. Recent data points to a contracting economy, possibly by larger margins than in the first quarter of 2020 when GDP contracted by 10.3 percent quarter on quarter.

China’s 5.5 percent real GDP growth target for 2022 seems impossible to meet. Undeniably, it’s headed for very low growth this year (2% at the most) even if there is a dramatic rebound in the second half. And a recession or economic contraction for the full year is becoming increasingly probable.

The official manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI) fell in July to its lowest level in three months. Clearly, Chinese manufacturers are still wrestling with high raw material prices, which are squeezing profit margins, and an export outlook that’s being clouded by fears of a global recession.

Similarly, freight and passenger traffic volumes, as well as property sales and consumption, have also fallen sharply as a result of COVID-19 restrictions; and they’re resulting in a massive disruption to China’s economy.

Policy support, which has often focussed on infrastructure construction, has also fallen short with activity being constrained by lockdowns and restrictions as in other sectors.

Despite these signals of a faltering economy, China’s official growth forecasts point to only a moderate slowdown. There are some reasonable arguments as to why growth may slow only modestly, particularly if China abandons its COVID restrictions altogether, and resorts to substantial cuts in interest rates and stimulus to the property sector.

But this path seems highly unlikely for two reasons…

First, restrictions are more likely to lift gradually. Second, the property sector is likely to remain a major drag on investment growth this year. Given the dramatic disruptions that China’s zero COVID policy has created, it is difficult to pinpoint which sectors will grow in 2022.

More problematic are some of its longer-term constraints on growth. China’s economy is unlikely to bounce back to the rates of growth seen before the pandemic – because even before the wave of new lockdowns was imposed, its economy was suffering considerably from the weakening property sector.

Notably, the property sector represents around 25 percent of GDP. Over a longer horizon, China’s growth outlook is constrained by demographics; falling productivity; and more significantly, failed structural reforms of the past decade.

According to US-based think tank Rhodium Group, the country’s potential growth rate at present is probably closer to three rather than five percent, and China is currently growing well below that putative rate.

Current Bloomberg consensus expectations for GDP growth are 5.2 percent in 2023 and 5.1 percent in 2024; but with the property market and financial system in distress, it may take several years to close that output gap – even if policy is more supportive.

A growth slowdown in China will have extensive implications for important global economic trends such as the demand for commodities, global inflationary pressures and carbon emissions to name a few.

An obvious transmission channel from slower China growth to the global economy is weaker demand and lower long-term prices for imported commodities, particularly those associated with construction activity.

In the short term, disruptions to the country’s supply chains and outbound shipments are inflationary due to the scarcity of key components. There is also a possibility that central banks may underestimate the disinflationary pressures coming from a slower growing China and emerging market central banks could suddenly become (as they did in 2014/15) far more dovish than expected.

The effect was pronounced in commodity prices – Bank Indonesia’s turnaround from hiking rates in November 2014 to cutting them in February 2015 is an example. Investments in low-carbon energy production are likely based on current expectations of China’s own growth in energy demand and carbon emissions, which may simply fail to materialise.

Overall, slower GDP growth in the years ahead is almost certain to alter the medium-term trajectory of global carbon emissions.

In many ways, 2022 represents a watershed year for China with huge doubts cast over its growth prospects and future position in the global economy. Let’s hope for only a moderate slowdown (against all odds) in China – because otherwise, the implications for the global economy could be severe.

Leave a comment