BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

Bertrand Russell said that power is the ability to produce intended effects. The results of what happened in Sri Lanka in January 2015 – when President Mahinda Rajapaksa was defeated; and more recently, when the powerful leader of the Maldives President Abdulla Yameen was also defeated – are examples of people power exercised mostly through social media.

Though this was an unimaginable phenomenon a few years ago, social media is now a very powerful factor globally.

With an election to run from 11 April to 19 May, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is feeling nervous. The tension in India rose over the conflict with Pakistan and even the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) has been under pressure to forfeit India’s game against their traditional rivals at the 2019 ICC Cricket World Cup, which commences at the end of May.

But this is an absurd policy! If India and Pakistan end up in the final, are the Indians going to forfeit the World Cup to Pakistan by not playing the match?

One hopes that social media will play a suitable role to militate against such absurd suggestions.

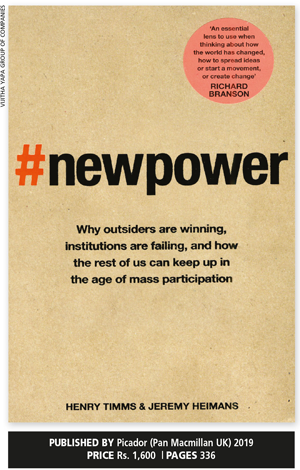

It is this new power of social media that authors Henry Timms and Jeremy Heimans expound. They say that while technology has changed, we too are changing through our behaviour and expectations. Their book is about how to navigate and thrive, in a world defined by the battle between two major forces – the old and new powers.

The authors claim that old power is like a currency that’s held by a few who obtain and jealously guard it. They’re powerful and have a substantial store to spend from. New power operates differently – it uploads and distributes power whereas old power hoards it.

Timms and Heimans point to the battle between the #MeToo movement and movie producer Harvey Weinstein. His alleged sexual harassment and assault has thus far been suppressed because he was powerful, and had shaped the fortunes of an industry.

Actress Terri Conn’s statement under the hashtag #MeToo claiming that she’d been assaulted by movie director James Tobac resulted in more than 30 women coming forward to accuse him of sexual harassment. One million tweets used the #MeToo hashtag during a 48 hour period and 12 million Facebook comments were recorded in a single day.

This in turn led to a worldwide campaign on many fronts and resulted in the resignation of the UK’s Defence Secretary Michael Fallon.

The authors say that the #MeToo hashtag gives users a sense of power and courage, to speak out against sexual harassment and abuse.

Another example is Scotland’s Aqsa Mahmood who attended private schools but became a ‘bedroom radical.’ A victim of persuasive content and seductive recruitment practices, this 19-year-old disappeared and called her parents from the Syrian border as she joined ISIS. She then used the internet to recruit others to join the extremist militant group.

The authors point out that her makeshift metastasising network is participatory and tear driven, and moves not top-down but laterally in girl to girl recruitment. They say these are examples of how today’s tools are used to channel an increasing thirst for participation.

Until recently, opportunities to participate and agitate were much more constrained. Through today’s ubiquitous connectivity however, people can come together and organise themselves, in ways that are geographically boundless and highly distributed – and with unprecedented velocity and reach.

The most important aspect of this book is that the future will be a battle over mobilisation. And people’s leaders who flourish will be those who are able to channel the participatory energy of those around them for good, bad or trivial goals.

Discussions around this subject include how to create ideas that people will latch on to – and then, through their own interpretations, make them stronger and easier to disseminate. This has created new elites.

The authors point to Facebook where there are more than two billion users who don’t benefit from the massive economic value created by them.

They note that the internet’s pioneers dreamt of an organic free roaming paradise but today, we live in a world of participating palms where a small number of big platforms have harvested profits for their own gain through the daily activities of others.

This book abounds with examples of what social media has achieved. But what would happen in Sri Lanka if this type of social media activity is used to pressurise politicians to desist from engaging in bribery and corruption, and put the country first?

Could this also be a powerful factor in elections that are due in Sri Lanka this year and the next?