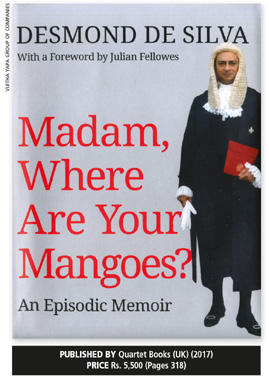

BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

At a private audience with Pope John Paul II at the Vatican, His Holiness turned to Sir Desmond de Silva’s wife – Princess Katarina of Yugoslavia – and said: “I hope democracy will come to your country as it has done to Poland.”

At a private audience with Pope John Paul II at the Vatican, His Holiness turned to Sir Desmond de Silva’s wife – Princess Katarina of Yugoslavia – and said: “I hope democracy will come to your country as it has done to Poland.”

With his Anglo-Sri Lankan puck working overtime, Sir Desmond couldn’t resist telling the Pope: “Your Holiness, I am delighted to see that you are a Pole first and a Pope second.”

“It is said that in a momentarily ice atmosphere, the only sounds came from the cardinals, imitating a dozen kettles with a sharp collective intake of breath,” says Paul Cheston, who wrote the case commentaries in this book.

This is typical Sir Desmond: his sharp tongue is indifferent to whom his comments are directed at. While the book is a veritable who’s who in British legal history, it has also documented a number of fascinating cases.

Sir Desmond is a legend in British legal history largely because of the number of cases where the accused he defended got off scot free. He is the grandson of ‘Apey George’ of Kandy who was at the forefront of Sri Lanka’s battle for independence and in whose memory a statue has been erected in Kandy.

Few know that Sir Desmond was also once the owner of Taprobane Island (of Count de Mauny Talvande fame) in Weligama.

In this delightful autobiography, he takes the reader through pages replete with examples of his sharp mind and unforgettable humour. When a diary columnist at The Times (UK) once said that Sir Desmond spends UK£ 400 a week on Armagnac, he is reported to have threatened to sue the journalist. “Outrageous slur that damages my reputation,” he griped, adding: “I spend much more.”

From the hallowed legal beat in the UK, Sir Desmond was thrust into global prominence when he became the first British Chief Prosecutor in an international criminal court. The man in the dock – who was found guilty of war crimes – was the former President of Liberia Charles Taylor who Sir Desmond described as ‘Africa’s Hitler.’

He studied common law in the UK and gathered useless information such as the definition of ‘ambidexter.’ And his first case came when he was asleep – he was snoozing in the rearmost bench of counsels’ row at Middlesex Quarter Sessions when the judge said: “Mr. de Silva, your moment of glory has arrived.”

Sir Desmond found that all the other barristers had vanished, realising that the next to be called up was a dock brief where a prisoner could choose his counsel in court for a measly designated sum.

Indeed, amusing occurrences in court always attract a reviewer’s attention.

One such incident was a request by a police officer for an adjournment of a case to analyse the contents of a drug parcel found on the accused. The judge ordered that the sealed sample be brought before him. He tore open the packet, tasted the contents and declared that it was cannabis resin. Where was it found? he asked. The embarrassed cop replied that it was concealed in the anus of the defendant.

Sir Desmond’s reputation for having defendants walk away from court is legendary. In Sierra Leone, he faced the wrath of a judge when he was about to argue that the foreign minister in Siaka Stevens’ government was a liar. He was arrested on a trumped-up charge, sent to prison and rewarded with malaria.

On another occasion, he was in Sierra Leone with Sri Lankan expatriate lawyer Noel Gratiaen, defending some political prisoners. They were staying at the Paramount Hotel and on their way to their rooms after dinner, the two were accosted by a few pretty ladies.

When asked if they’d like some mangoes delivered to their rooms, Sir Desmond declined but Gratiaen said ‘yes.’ A few minutes later, there was a commotion outside and Sir Desmond found Gratiaen standing outside his room with a pretty woman who was naked down to the waist, shouting: “Madam, where are your mangoes?” Desmond says she didn’t get paid but he now had the title for his book.

The section on astrology is also fascinating. An astrologer had once told Sir Desmond’s grandfather George E. de Silva that he would die on the Ides of March. One day in March, after playing a four-hour session of golf, he collapsed. When he learnt that the date was the 12th, he had said he’s done since it was the Ides of March. He died soon after.

There’s another story about a domestic aide who worked for his grandfather. The man had been told by an astrologer that his lifespan was limited as the lifeline on his left palm was short. In an attempt to alter his fate, he scratched a furrow on his palm with a nail in the hope of extending the lifeline. Within a week however, he suffered from blood poisoning and died.