BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

At the time of writing, the campaign to elect Sri Lanka’s next president is in full swing. But once the election is over, the time will be right for healing – and a superhuman effort will be needed to redirect our island nation on the right path. It’s in this context that the book titled ‘Thomian National Heroes of Sri Lanka’ is significant.

President of the Political Science Society of S. Thomas’ College (STC) Uthsara Dunusinghe has understood that the need of the hour is healing and finding a way forward. And what better way is there than by focussing on national heroes who had their early education at STC?

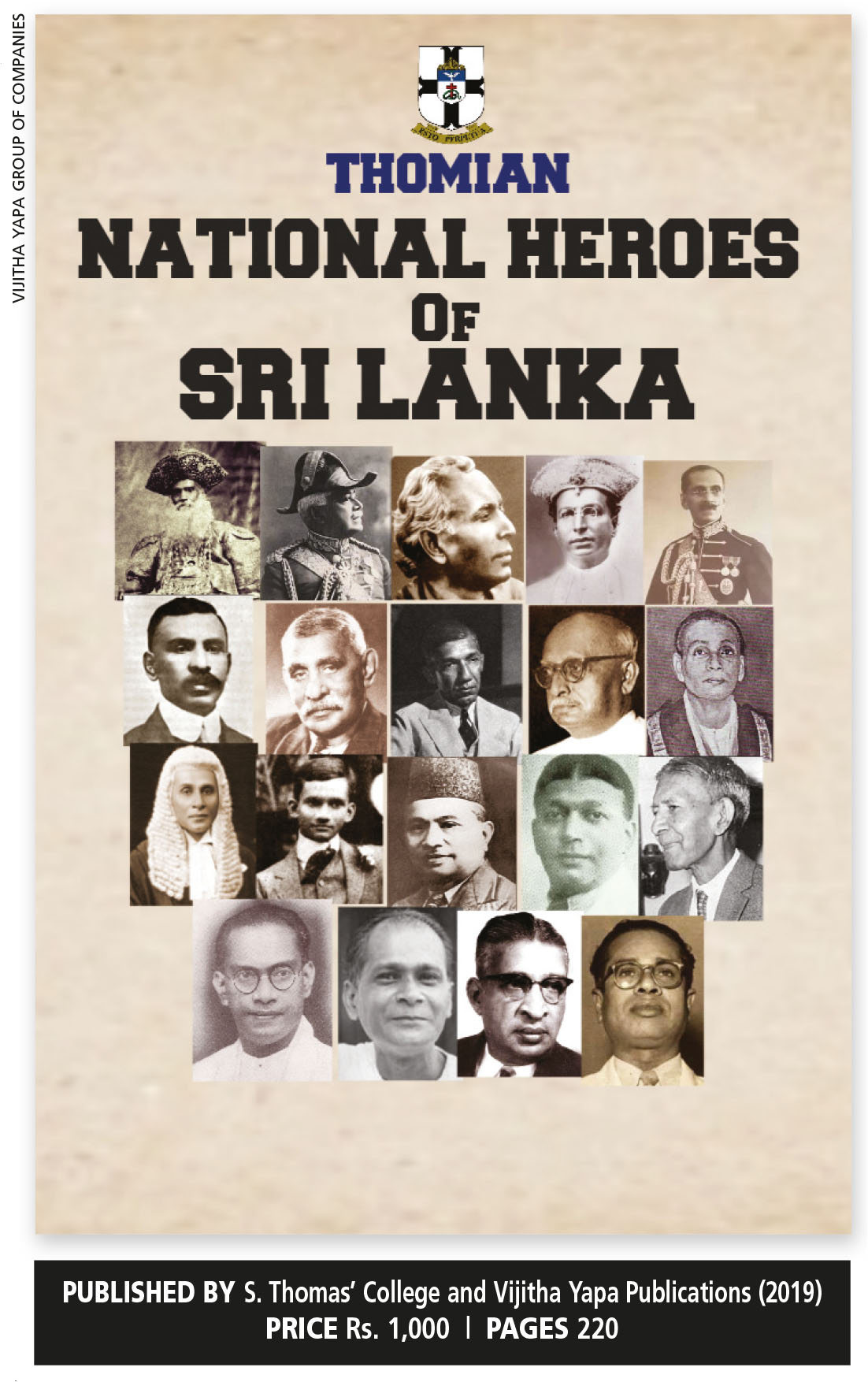

Although only 19 personalities have been commemorated, what a list this is! There are Sinhalese, Tamils, Muslims, Malays, Colombo Chetties, Buddhists, Hindus and Christians, creating a tapestry of citizens who have shaped our land.

STC Warden Reverend Marc Billimoria writes in his foreword: “It’s ironic perhaps that the very system of liberal education introduced by the British colonial masters proved to be the foundation of the unravelling, decline and fall of their Empire upon which the sun was never meant to set!”

It was Sir Winston Churchill who originally envisaged the sun never setting on the British Empire, to which Dr. Colvin R. de Silva’s cheeky response was: “That’s because God doesn’t trust the British in the dark…”

An important aspect of the book is that it consists mainly of essays written by close relatives. The first article is on Maduwanwela Maha Disawe – a.k.a. the Black Prince of Ceylon – who ensured that anyone who entered his abode had to crouch as the doorway was not very high.

He was a man of immense wealth with more than 80,000 acres (323 square kilometres) of land bequeathed to his forefathers by King Vimaladharmasuriya II.

And he behaved like a king. When villagers suffered because there was no bridge and his appeals to the government agent (GA) failed, he invited the GA to a meal. The former then ensured that the latter was carried on a palanquin around the area and asked his men to tip it when crossing the stream so that the GA fell in! A bridge was constructed in a few months.

Victor Corea of Chilaw is another outstanding figure featured in the book. He was at the forefront to free his people from British rule. His letterhead featured a gold imprint of a lion resting its head on its paws with the words: “Awake not the sleeping lion.”

It’s not known whether these words were reminiscent of Napoleon Bonaparte’s prophesy about China: “China is like a sleeping giant. Let her sleep as when she wakes, the whole world will tremble.”

And though China is now wide awake, Sri Lanka’s lion continues to slumber.

When the British announced a poll tax of Rs. 2 on every male over 21 years, Corea refused to pay it and took up cudgels against the state. Wishing to use the offender’s consequent prison sentence as an example, the colonial administrators put him on display as he laboured under rigorous imprisonment. But he was granted special privileges such as a bed to sleep on and European cuisine of his choice – perhaps because he was a lawyer in the Supreme Court.

However, Corea rejected both perks and chose to sleep on a hard wooden plank and ate regular meals served to other prisoners. What a contrast to today’s incarcerated leaders who crave special status. Corea was successful in his mission and the poll tax was withdrawn.

Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake was a giant among old Thomians. His father threw a party when his son revealed he’d come fourth in class. But proud papa forgot to ask his progeny how many there were in the class – and certainly, D. S. didn’t reveal that there were only four!

Meanwhile, the educational qualifications and achievements of our leaders are highlighted even today.

This Prime Minister of Ceylon signed a defence pact with Britain at the time of independence in 1948 because it gave him security. Today, we’re mired in controversy with China, the US and India vying for a special relationship with Sri Lanka because of the island’s geographical position.

Though we remember J. R. Jayewardene as the one who spoke in favour of the Treaty of Peace with Japan at the San Francisco Conference in 1951, we learn that J. R. was in fact articulating Senanayake’s policy. In an article in the Ceylon Historical Journal, he noted that at the Colombo Conference of Commonwealth Foreign Ministers in 1950, D. S. had strongly favoured full amnesty for Japan and it was this position that J. R. expressed in San Francisco.

The constellation of personalities featured in this book showcases those who led from the front in Sri Lanka’s battle for independence.