BOOKRACK

Romance novels are usually the rage in schools – and their popularity among young people is an indication that they enjoy reading such books.

In the West, these are usually printed on cheap paper and made available at nominal prices. They sport dazzling and provocative covers to attract young readers, and usually involve the romances and escapades of a young girl with a stranger whom she has met at a party or on the street.

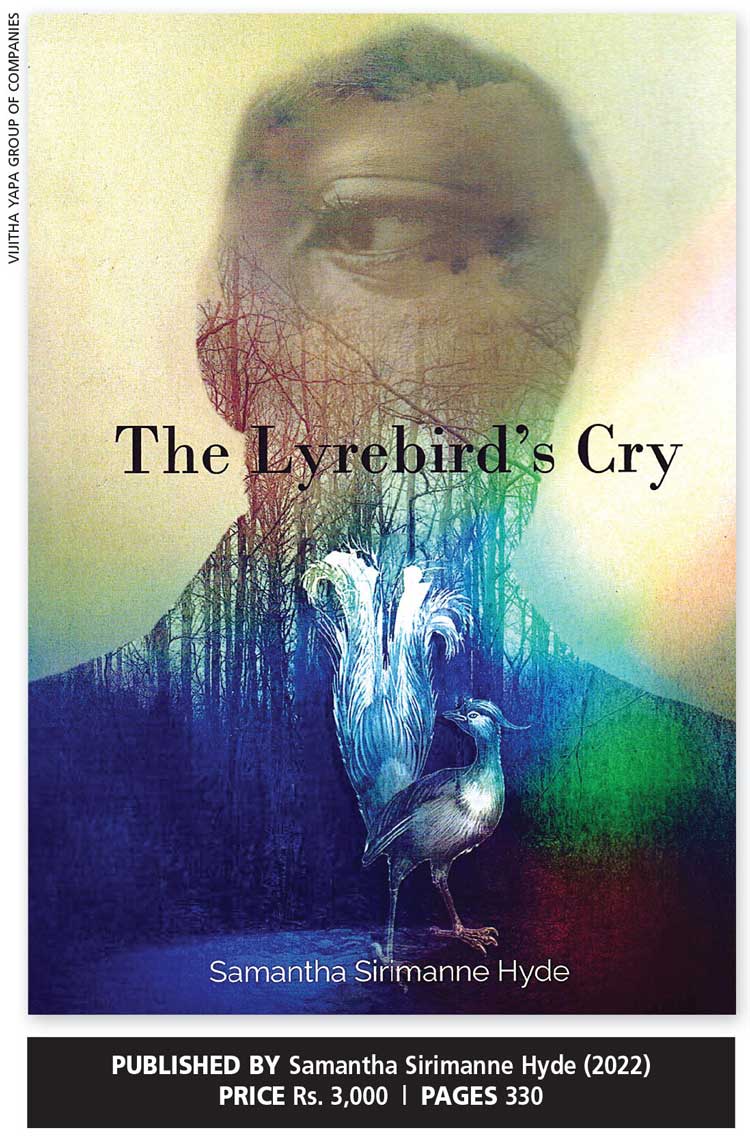

The Lyrebird’s Cry by Samantha Sirimanne Hyde is quite different and not the usual regurgitated plot. The story revolves around Jagath, who is in Australia for his studies, and his decision to return when his father offers to pay for the ticket. Jagath is awaiting permanent residency documentation from the Australian government so that he can register himself for citizenship.

But the call he receives is a summons: that of his father asking the son to come back. With Aluth Avurudu round the corner, Jagath thinks it would be an excellent time to enjoy the celebrations and meet his friends.

His father, though, has other ideas. He wants his son to tie the knot with a girl he has never seen – for Jagath to marry a woman who is completely unknown to him. This is the way some marriages are arranged and take place in Sri Lanka – much to the annoyance of brides and grooms who may have other plans or interests!

Here the story takes a different turn. Jagath isn’t interested in marriage because he’s already embroiled in an affair in Sydney. The complication is that the partner he’s living with is a man. They met when Jagath lost his credit cards and related documents, and had to seek assistance from the bank. The bank official responsible for issuing new cards is a Sri Lankan named Randy.

Jagath’s father has already arranged for the bride’s parents and their daughter to visit them the next day. And the matter of the dowry has also been settled.

But the complication is that Jagath doesn’t want to marry a girl. And he does not communicate this to his parents because the father insists that a son must do whatever he’s told. He reminds Jagath that millions of rupees have been spent on his education and therefore, it is his duty to obey the father’s wishes.

Though many countries have now passed legislation that enables gay people to be recognised, permitted to live together and even register their marriages, Sri Lanka doesn’t have such laws in place. Its minority gay community has not been successful in challenging the status quo so that they can live together legally.

The author describes in detail the dilemma that Jagath faces in a society in which there isn’t much hope for recognition of gay marriages. She uses the vernacular to describe some events; but unfortunately, this means referring to the back of the book to check its glossary to understand what the author means. A footnote at the bottom of the page would have been more helpful – especially for foreigners.

In Shyam Selvadurai’s book Funny Boy, the scenario is different since the focus is on the lives of the main characters who are gay.

The basis of the plot in this book is the relationship that Jagath has with his family in a society that doesn’t look kindly upon sexual relations between two adult men. Love and hate, good against evil, a battle to manage what society demands and the individual’s desires are among the issues addressed in this novel.

It is based on the true-life experiences of a young adult, Jagath, and the forces that are at work in his life as he wrestles with his emotions and the realities of life. The Lyrebird’s Cry takes into account what is desired of him and that which he desires for himself.

Inclusion of lines from the Dhammapada to head each chapter is an excellent way of drawing readers’ attention to areas with which he or she may not necessarily be acquainted. The book focusses on life, sundry demands and expectations of a middle-class family in Sri Lanka, and what their sacrifices in terms of financing an expensive education in a developed country entail.

On the other hand, the son demands a life of his own and wrestles with his thoughts, which he cannot discuss with his parents because of the taboos dominant in South Asian countries.

The author has published the book in Australia where she lives and understands what’s demanded of a writer in terms of greater detail. She has chosen ‘The Lyrebird’s Cry’ for the title – referencing a creature that produces “a dizzying array of sounds, which would cause most birds to hang their heads in shame.”

Jagath faces a similar dilemma as he tries to decide what sounds he should produce to please society.