AGRICULTURE SECTOR

GROWTH UNDERMINED

Samantha Ranatunga calls for public-private endeavours to develop the agriculture sector

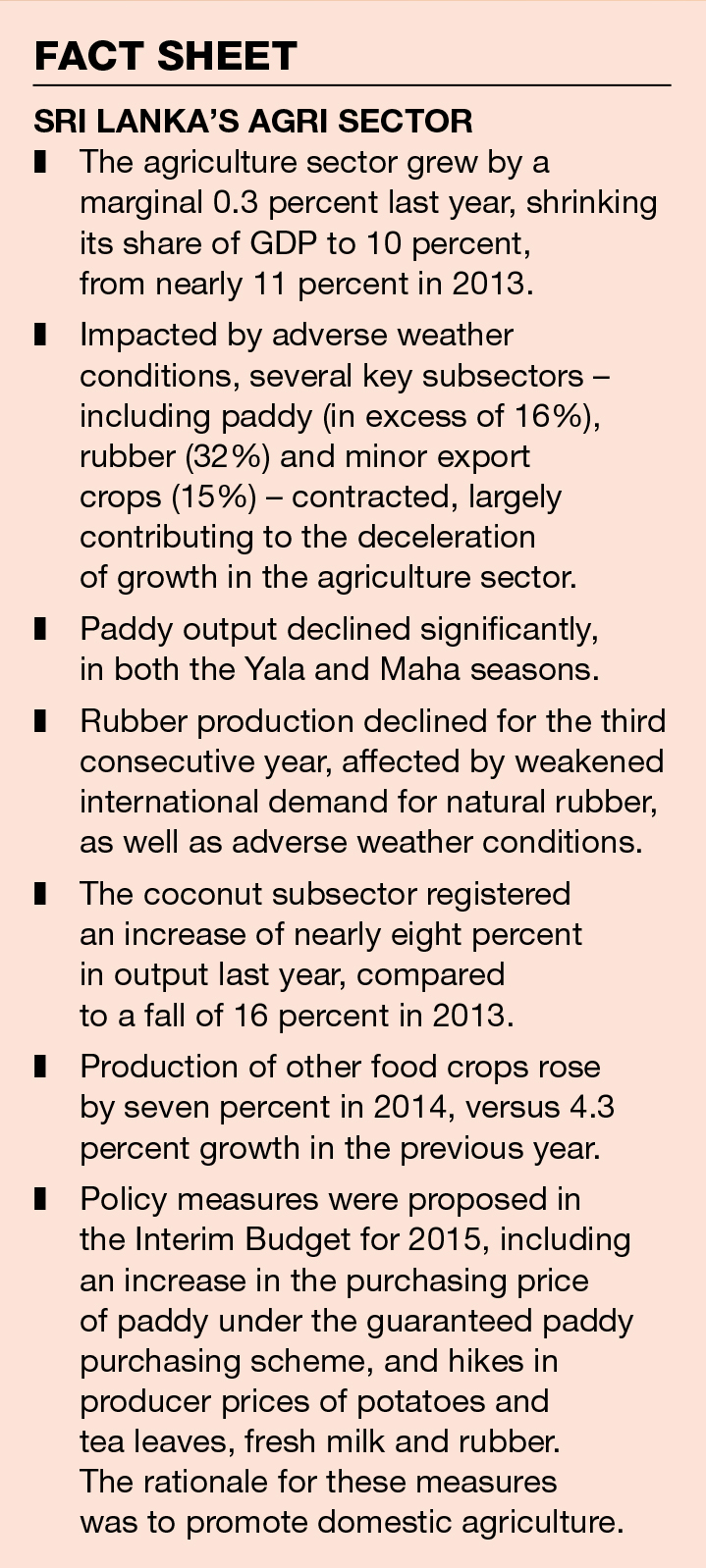

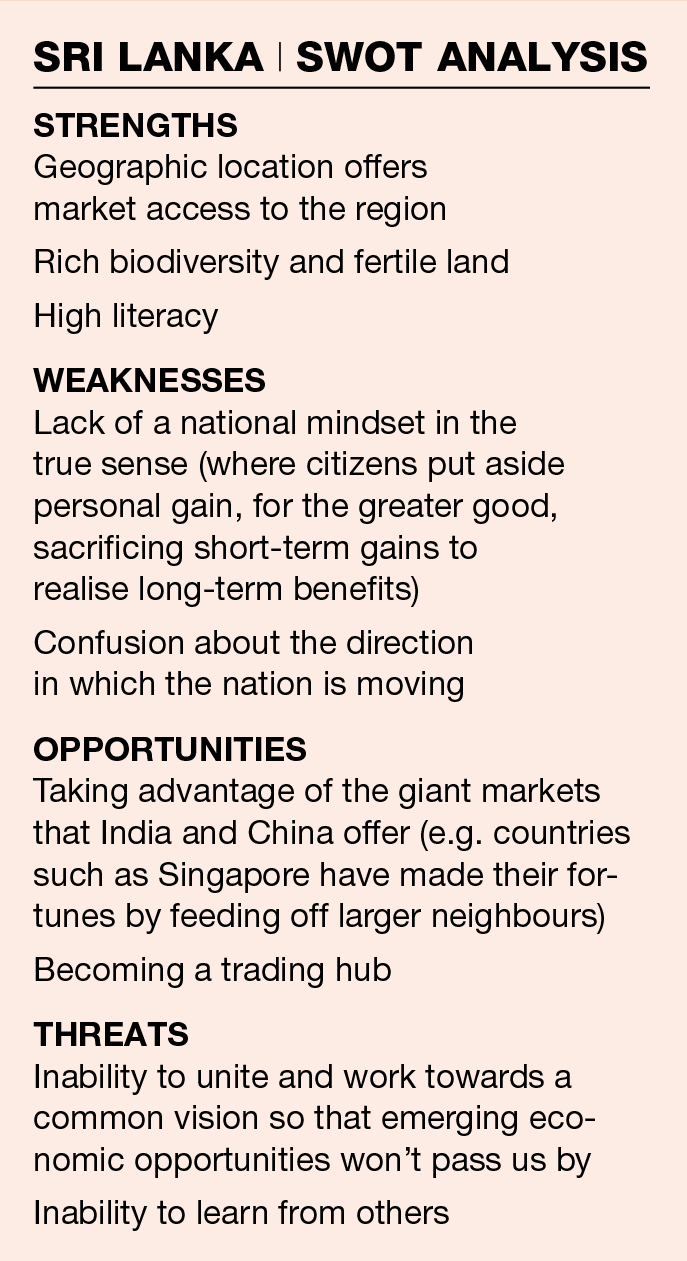

Despite Sri Lanka’s rich legacy of agriculture, advanced irrigation techniques and an abundance of fertile land, its contribution to the national economy stands at a somewhat meagre 10-13 percent. Considering that 65 percent of the population is located in rural areas, agriculture hasn’t mined its full potential.

The immediate aftermath of the war witnessed an upsurge in agriculture, largely due to some 300,000-400,000 acres of land in the war-torn north and east being released for cultivation. However, apart from that initial glimmer of optimism, sector growth has largely stagnated. More significantly, the profitability of farmers has not improved in any shape or form. It is amply evident, therefore, that they’ve been left behind, in Sri Lanka’s push for higher growth and prosperity.

Samantha Ranatunga explains that “there are many challenges to achieving growth in the agriculture sector – and ironically, this is common knowledge. Despite being a subsidised sector, farming has struggled to grow because it is now being steered by an ageing population, as the younger generation is moving away in pursuit of urban employment.”

“As a result of this urban migratory trend, landholdings are disintegrating, with farmers being forced to subdivide their land into smaller tracts, either to be disposed of or apportioned amongst their offspring. Retaining youth and future generations in the business of farming will be the stiffest challenge that the sector is likely to face,” he observes.

REGIONAL REALITIES However, the scenario is different in the east of Sri Lanka, where farmers are aggregating land by putting smaller landholdings together, to reach critical mass.

This cooperative spirit is driving substantial gains for the farming community in this region. Commercial viability is lending them the capability to share harvesting costs, leading to greater mechanisation, more negotiating power with buyers and higher market prices. “The secret of the success of the farming communities in the east of the island lies in their strong business focus and ability to view farming as an entrepreneur would a business. Farmers in the south tend to look at farming as a tradition that should be upheld in the same manner their ancestors did; and therefore, they do not seek to drive greater economic benefits, being content to eke out modest returns,” Ranatunga notes.

On the other hand, agricultural land in the north is now under cultivation especially in the regions of Mannar – the rice bowl of Sri Lanka – Vavuniya and Kilinochchi.

The opening of the A9 highway, connecting the north to the south, has been a blessing. It offers market access, the single-largest hurdle faced by northern farmers during the war. The people of the north have learnt resilience over decades of war, which required them to become self-sufficient. Today, they are a step ahead in adopting technology, foraying into horticulture and modernising farms.

CHANGING MINDSETS Ranatunga asserts that “a step change is needed to infuse the sector with technology. Unless there is a mindset change amongst the farming community, and it realises the benefits of mechanisation, the ground realities will not change. Agriculture should not be equated with poverty. Unfortunately, this perception is all-pervasive.”

He continues: “Recently, CIC undertook an ad campaign to try and change this perception, by erecting billboards that depicted farmers wearing suits. We learnt that interest groups pelted these boards with cow dung because they felt this wasn’t the image of a traditional farmer. Farmers have to shed this age-old perception of social ostracisation, aided and abetted by a subsidy regime, which makes them more dependent on retaining the status quo.”

Decades of granting subsidies to farmers has made them incapable of imagining a future where they would realise higher yields by adopting best practices and technology, rather than relying on subsidies.

SOCIAL SOLUTIONS So what is the solution to this conundrum? The industry leader replies: “We need a merit-based approach – a pay-for-yield-output type arrangement, where farmers are motivated to improve yields by adopting modern methods, to increase output and generate higher incomes. It is also important for farmers to have access to finance so that they don’t have to start a new planting season in debt.”

Meanwhile, product innovation is crucial for growing the sector, he adds.

Although microfinance is gaining ground in Sri Lanka, it has not been as impactful as in Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia. But Ranatunga feels that access to microcredit is not a huge challenge – not as much as value addition and technology adoption.

Yet, he does not want to place the blame at the government’s door. In his view, this is first and foremost a social issue – to change the perception of farmers having little or no dignity of labour. How we should engage the farming community, attract young blood and help them find new markets… they are the key questions. As for investors, government policies need to assure ROIs, as only then will more foreign investment and private sector companies enter the sector, he remarks.

SECTOR HEALTH The sector is largely dependent on the fertiliser trade, which is highly regulated and sometimes causes roadblocks to planning farming cycles.

“More often than not, fertiliser companies are looked at with suspicion. In the North Central Province, which has a high incidence of chronic kidney disease, the blame is being put on fertilisers. But the rock phosphates in the area also contain naturally occurring arsenic, which could leach into the soil and village tanks,” he adds.

In any case, Ranatunga asserts that the agrochemicals business is “now a threatened industry” that will soon be overrun by organic products. Since Sri Lanka is considered an ecological hotspot, the nation needs to optimise its land use productively, he adds.

One of the first goals should be to become self-reliant in rice production. Sri Lanka produces more rice per acre than India and Thailand, so there’s no reason why it cannot move rapidly towards gaining self-sufficiency. However, supply chain issues (e.g. storage facilities) need to be tackled first.

POLICY REVIEW In Ranatunga’s view, the country’s industrial and agricultural policies are akin to a colonial legacy, untouched by the spirit of entrepreneurship or innovation.

“We need new economic models to boost vital sectors. Our land taxes need to be reviewed and revised. Farmer societies need to be established, and foreign investment in the sector should be facilitated. Today, we don’t have a major exporter of fruits and vegetables. Why is that? We have the right climatic conditions for it,” he argues.

That the sector lacks vision is apparent because, despite knowing the problems, there’s no attempt to resolve them, Ranatunga laments. And he cautions that “if in the next four to five years, we don’t make a step change, we will never grow beyond [our] current levels.”