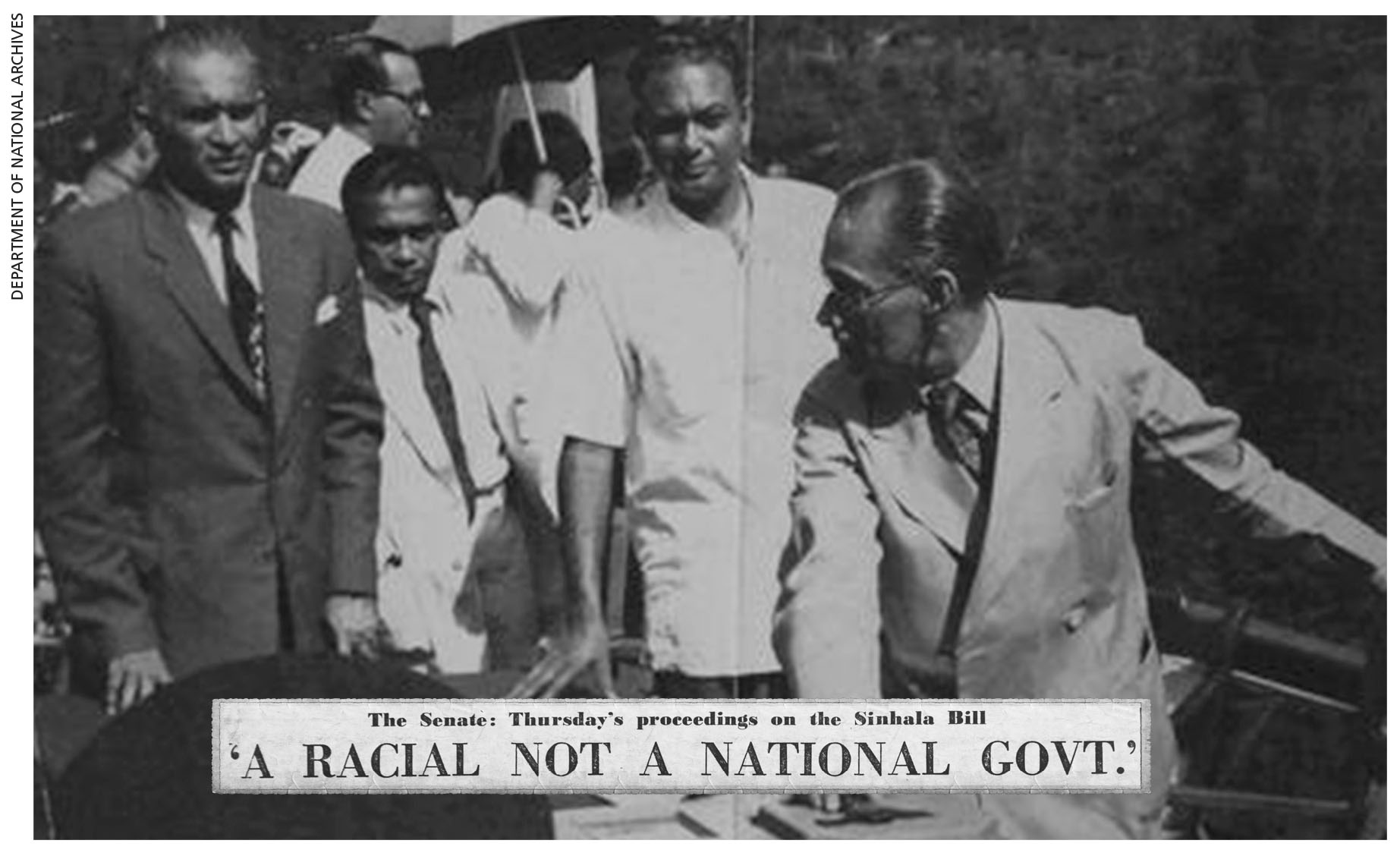

1956

Sinhala Only Act Creates Divided Nation

Language proves to be an ethnic flashpoint

A single person’s ambition often spells peril for the people of a nation. But it may not be as simple as later interpreters of history make out the divisive events of 1956 to be. It was a year in which the destiny of an island nation was perhaps changed from ‘unity in diversity’ to ‘adversity amidst disparity’ by the stroke of a pen.

One factor in the ratification of the chauvinistic Sinhala Only Act – more formally, the Official Language Act (No. 33 of 1956) – was that it was the brainchild of a brilliant political mind; an ambitious soul that had been born to privilege, and bred and educated among the elite, English-speaking Western orientated upper classes of his day in postcolonial Ceylon.

A product of S. Thomas’, his experience of racism at Oxford ostensibly soured his outlook.

But equally germane were the aspirations of the political party that he – the redoubtable Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike (the Christian names speak volumes for his provenance) – founded. That centrist organisation, the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), was politically ambitious and desired to mount a serious challenge to the conservative United National Party (UNP), which had dominated at the national polls since independence.

Thus it was that whereas the UNP had let matters rest and allowed English to stand as the state language even after 1948, the SLFP broke ranks with the general consensus, which had been shaped by the leftist parties in opposition, that both Sinhala and Tamil be deemed national languages, and campaigned to carve out their electoral fate on a ‘Sinhala Only’ platform.

This was something of an irony since it was one of the UNP’s latter-day stalwarts – J. R. Jayewardene – who had moved in the State Council of Ceylon as far back as 1944 that Sinhala replace English as the lingua franca of the then-to-be independent state.

In the end, the chauvinists prevailed, setting Ceylon and Sri Lanka on a violent path that would see the post-independence Sinhalese majority’s determination to make Sinhala the state language a casus belli for a strident – and later, violent – Tamil separatist movement, which interpreted the act as being tantamount to oppression and the justification for minority rights militancy.

The SLFP broke ranks with the general consensus, which had been shaped by the leftist parties in opposition, that both Sinhala and Tamil be deemed national languages