US ECONOMY

‘HIGHER FOR LONGER’ IN PLAY

Samantha Amerasinghe analyses the US economy amid record high interest rates

The narrative of ‘higher for longer’ with regard to interest rates in 2024 is firmly in play – the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) for example, held its policy rate at a 22 year high at its September monetary policy meeting.

Other global central banks have followed suit. The Bank of England (BoE) and European Central Bank (ECB) are also reciting the same mantra due to hotter than expected inflation.

There are three main concerns for policy makers: whether to keep rates higher for longer, how oil prices will pose challenges to controlling inflation and if recession is still a threat.

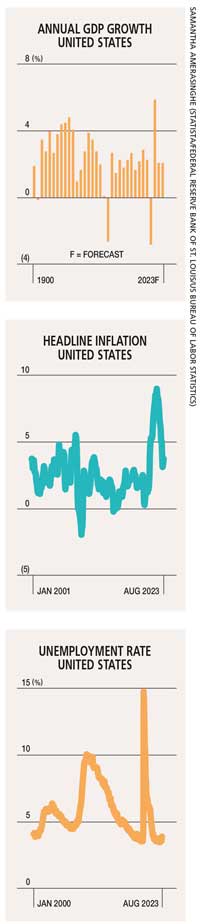

The US economy has certainly shown resilience this year in stark contrast to the troubles that China and Europe have experienced. Despite the most rapid and aggressive series of interest rate hikes in 40 years, combined with much tighter lending conditions, America continues to grow.

With inflation remaining above target and the job market still incredibly tight, the Fed’s latest economic projections indicate that higher borrowing costs are here to stay for the remainder of 2023. And one more rate increase has been pencilled in to lift the Fed’s fund rates to between 5.5 and 5.75 percent.

The outlook for interest rates next year hangs in the balance. Most federal officials see a much slower path of rate cuts in 2024, predicting that economic growth will remain relatively robust and unemployment won’t rise materially.

Policy makers project that the economy will expand by 2.1 percent this year, followed by 1.5 percent in 2024. And the unemployment rate is expected to peak at 4.1 percent over the next couple of years.

The central bank’s benchmark rate is expected to fall to between five and 5.25 percent next year – that’s substantially higher than prior projections – as the US economy has remained far more resilient to elevated borrowing costs than expected.

Policy makers forecast that core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices, will ease to 3.7 percent by the end of this year before falling to 2.6 percent in 2024. This measure, known as the Core Personal Consumption Expenditure Price Index (PCE), hovered at 4.2 percent in July.

A sharp consumer slowdown coupled with weaker hiring and poor external demand are among the additional concerns that policy makers are grappling with. They could quickly reignite recession worries – especially if rising commercial real estate delinquencies and defaults put more pressure on the still stressed regional banks.

Another concern for the Federal Reserve is the upward trajectory of oil prices. They have been on the rise over the past few months – exceeding US$ 90 a barrel and posing a challenge to the ability of central banks to bring inflation under control – while rising fuel costs could weigh on economic growth.

Although higher energy prices will keep headline inflation elevated, slowing housing inflation and competitive pressures will constrain core inflation, and offer the Federal Reserve flexibility to respond to the threat of recession.

This won’t be the first time that oil has frustrated the Fed’s efforts to bring inflation down to its target level of two percent.

In the 1970s, multiple supply crises in the Middle East led to key benchmarks spiking above 120 dollars a barrel (in today’s money) and a period of stagflation, which is a combination of soaring prices and weak growth that the Fed was unable to fix.

Supply cuts by Saudi Arabia and Russia have fuelled concerns of a shortfall that could harm the global economy. Riyadh and Moscow announced that they were extending their voluntary oil supply cuts (which were originally slated to expire in mid-2023) until the end of the year, in their attempt to preemptively manage supply in case global growth slows.

Consequently, supplies and inventories remain tight to limit the downside in oil prices.

Oil policy continues to be a bone of contention as Riyadh favours higher prices to fund its ambitious economic and social reforms.

Major oil producers have been angered by the push towards renewable energy sources and electric cars, which they view as long-term threats to their economic security. Western governments have championed renewable energy more aggressively in recent years but are still keen to keep oil prices moderate to support the wider economy.

The West also wants to ensure that Russia is not flush with oil revenue, which is the largest contributor to its budget.

President Joe Biden is under pressure to keep oil prices in check amid Saudi Arabia’s moves to deepen and extend production cuts. His administration is keen to retain its influence over Riyadh due to the latter’s strengthening links with Beijing and Moscow.

Higher oil prices and inflation will keep interest rates high for longer in 2024, and analysts believe that this mantra will prevail at least until the second half of the year – although any threat of recession is likely to dissipate.

Leave a comment