WORLD ECONOMY

GROWING (INFLATION) PAINS

Samantha Amerasinghe elaborates on the fight against inflation in the West

One of the chief macro challenges facing the world economy is inflation. Central banks are entering a new phase in the battle against inflation and more interest rate rises are looming – with more pain on the way.

One of the chief macro challenges facing the world economy is inflation. Central banks are entering a new phase in the battle against inflation and more interest rate rises are looming – with more pain on the way.

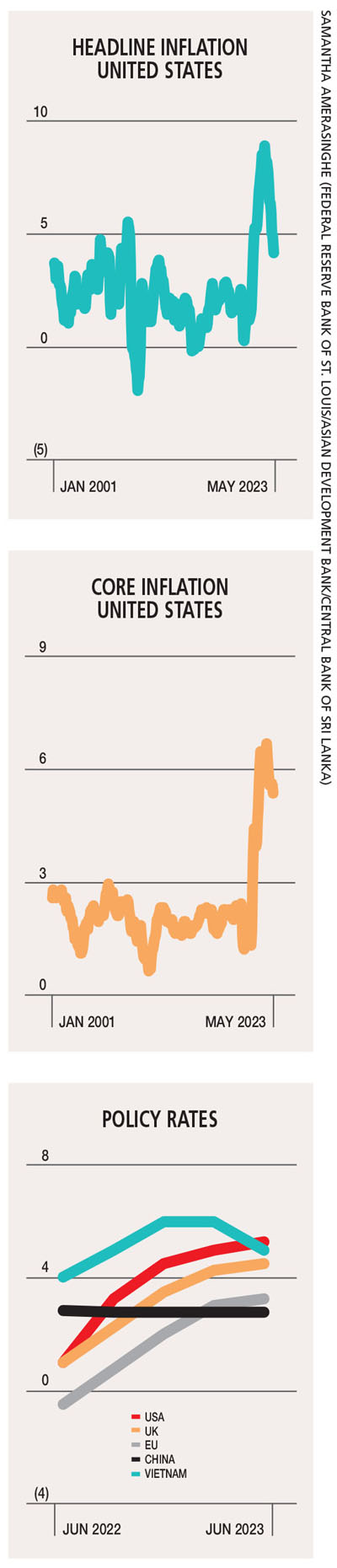

Despite headline rates of inflation cooling across most of the world’s economies, core inflation (which excludes volatile categories such as energy and food) remain stubborn, and are at or close to multi-decade highs, particularly in the West.

Core inflation, seen as a better gauge of underlying price pressures, has sparked concern that central banks will struggle to hit their shared two percent target without dire consequences for growth.

Core inflation, seen as a better gauge of underlying price pressures, has sparked concern that central banks will struggle to hit their shared two percent target without dire consequences for growth.

And many economists have warned that a recession will be the price of achieving two percent inflation.

For context, the US Federal Reserve’s favoured measure of core inflation is the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI), which has hovered at around 4.7 percent for the past six months while the Eurozone’s index has been sticky at about five percent.

Although the initial drivers of this bout of global inflation have been reversed – namely supply side factors and lax monetary policies – the second round of inflation effects is feeding into core inflation in economies such as the UK.

This points to more pain and a potential recession in the second half of this year.

According to the latest projections by Fed officials, more robust US growth is expected in 2023 than seen three months ago. However, the unemployment rate is expected to peak at nearly one percentage point above its current level of 3.7 percent – and an increase of that magnitude is indicative of a recession.

Globally, headline inflationary pressures are easing. Freight rates and oil prices are low, and food prices – according to the UN’s measure – have come down by roughly 20 percent from their all-time high in March last year.

China has also eased rates and is likely to cut its reserve requirement ratios for banks again to provide liquidity. This is a reversal of its more prudent approach to monetary policy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While many countries are likely to have seen policy rates peak, central banks are reluctant to signal easing. For instance, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has kept policy rates on hold despite inflation easing to a 25 month low of 4.25 percent.

That’s because growth remains robust in developing Asia, and is expected to reach 4.8 percent in both 2023 and 2024. And South Asia, led by resilient growth in India, is expected to grow faster than other subregions.

Headline inflation in the region is gradually returning to pre-pandemic levels and inflation in developing Asia has been projected at 4.2 percent this year, driven by muted inflation in China.

The regional decline in inflation will be supported by monetary tightening, and easing of supply chains and shipping bottlenecks. In the West, the persistence of core inflation is keeping central banks cautious.

A major worry for policy makers is the level at which rates should be set rather than the pace, which is now less of a concern. Experts are divided on how aggressive central banks need to be.

Many have opined that eliminating high inflation is still fraught with risks and argue that it would be better for policy makers to err on the side of doing too much rather than too little. Other economists seem confident that price pressures are easing.

Tight labour markets coupled with rising inflation expectations are feeding wage growth. To have any meaningful impact on inflation, former Fed chair Ben Bernanke has warned that wages need to rise at a similar pace to productivity growth.

So where are interest rates heading?

At its monetary policy meeting in June, the European Central Bank (ECB) raised its interest rates by a quarter of a point while the Fed didn’t do so. That was a prudent move, given how far and fast the Fed had lifted rates since March 2022.

In a little over a year, the federal funds rate has risen from near zero to a range of between five and 5.25 percent. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell raised concerns that tightening of credit standards following the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) collapse in March could generate headwinds for the US economy.

Both central banks have signalled that the fight against inflation is far from over and warn of further rate increases ahead. The Bank of England was compelled to move aggressively by 50 basis points, given that core inflation had settled at 7.1 percent in May.

Markets are now responding to the renewed hawkish stances taken by central banks, and expect US interest rates to peak at between 5.25 and 5.5 percent – up from 5-5.25 percent in June.

In the Eurozone, investors are increasingly factoring in the possibility of rate rises in the near future. The US Fed has indicated its support for two more 25 basis point rate rises going forward this year.

Leave a comment