The countries with the most satellites in space

More than 1,950 active satellites are currently orbiting Earth, and plenty more could soon be joining them.

Reduced costs and growing competition has seen an increasing number of commercial satellites reaching Earth’s orbit, which – unlike national space programmes – don’t recognize national boundaries.

While some countries continue to view space through a military lens, collaborations such as the International Space Station have brought nations together to push the boundaries of knowledge about the universe.

This spirit of cooperation is also giving rise to a new breed of entrepreneur keen to exploit the untapped potential of the burgeoning space sector.

The new space race

Ambitious private endeavours in development include space mining operations, and programmes allowing fee-paying tourists to experience going beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

Business is also booming for the growing number of private firms offering satellite launch capabilities to private clients and national governments. This has helped the spread of satellite technology to less wealthy countries without space programmes of their own.

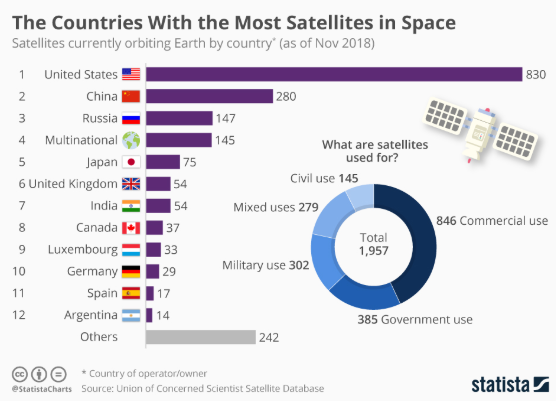

The UCS Satellite Database, compiled by the Union of Concerned Scientists, a nonprofit science advocacy group, shows that the United States, as of November 2018, had 830 registered units in orbit. That number almost exceeds the combined total of the rest of the top ten. China follows with 280, and Russia is third with 147.

Surprisingly, Luxembourg operates more active satellites than large European countries like Germany, Spain and Italy. The principality recently launched the Luxembourg Space Agency (LSA), which uses the launch capabilities of industry partners to encourage entrepreneurs to fulfill their commercial space goals.

Satellites owned by companies heavily outnumber those used by the military, which reflects a growing trend of the private sector becoming more involved in space technology.

Bringing governance to the final frontier

The surge in commercial space operations has increased access to satellite services for all, and fuelled a start-up race for new entrants to the market.

But the rush to get more hardware into orbit does have its disadvantages. Orbital debris, or space junk, can drift for many years and is a potential hazard for other satellites. There have been several costly collisions which have resulted in detritus spreading into space.

Another potential problem is radio frequency interference. When satellites are too close to each other and transmitting on the same frequency, communications signals can be distorted or even deliberately jammed.

While a disrupted TV signal may prove inconvenient, lost scientific data or interference with a military satellite could have more serious consequences.

To ensure long-term sustainability of outer space activities, the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) is drawing up best practice guidelines. Firms, governments and policymakers have a duty to improve governance in space, which includes helping the industry realize its huge potential responsibly.