SUPPLY CHAIN CRISIS

REINVENTING THE VALUE CHAIN

Samantha Amerasinghe elaborates on the need to address logistical bottlenecks

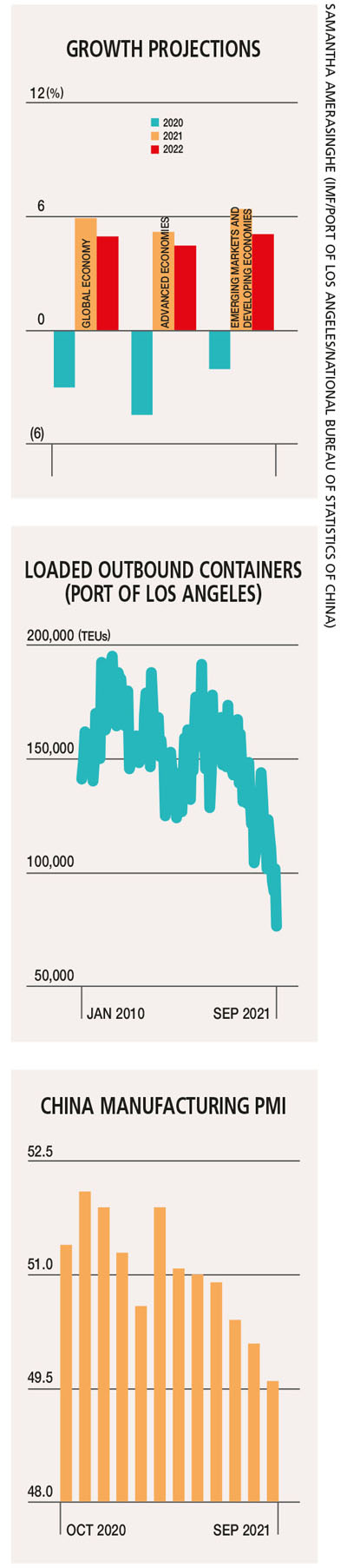

We are presently witnessing the worst disruption of the supply chain since the advent of the shipping container era in the late 1950s. It is no surprise that the IMF recently lowered its global growth forecast for this year to 5.9 percent (from 6%), citing supply chain disruptions in advanced economies as a key factor.

News about supply chain bottlenecks and stark warnings over shortages during the festive season have captured the headlines in the past few weeks. Many countries have been sounding alarm bells due to a backlog of unprocessed cargo sitting in their ports.

We analyse the three big forces driving the latest supply chain crisis and question whether it is fuelling a retreat from globalisation.

These forces are the pande-mic, the climate and geopoli-tics, according to the Peterson Institute for International Economics. All these factors impacted the recent semiconductor shortage that crippled automotive production worldwide.

The fallout from the pandemic has been largely responsible for soaring freight costs and delivery delays driven by a shift in consumer spending to imported goods – such as laptops and bicycles – as lockdown restrictions curbed spending at restaurants, sporting events and theatres.

Costs have skyrocketed – they are three times higher than at the beginning of this year and a staggering 10 times pre-pandemic levels. The average global price of shipping a 40 foot container is almost US$ 10,000.

According to one of the largest container port operators, the current supply chain problems could last for two years due to the world’s reliance on China for manufacturing.

At the time of going to press, more than 600 container ships are stuck across the world, waiting to clear the backlog of cargo due to increased demand for consumer products, pandemic related disruptions and a shortage of dock workers.

The problems are especially acute on the Asia-US route.

These logistical bottlenecks are blocking some one trillion dollars’ worth of toys, clothing, electronics and furniture from reaching the United States. And these costs are being passed on to consumers, pushing the price of imported goods up in Europe and the US.

Additionally, the supply chain crisis has brought to light the inefficiencies of the United States’ infrastructure, which has been continually beset by antiquated trade policies and practices.

A powerful union is at the core of the issue, which has led to substantial cost increases, limited ability to automate terminals, chronic avoidable disruption during contract negotiations, and far lower productivity and working hours compared to ports in Asia and globally.

US port facilities are far behind top performing installations around the world, and generally less automated and efficient than those in other economies. For example, it takes twice as long to move a container from a large ship at the Port of Los Angeles than it does at some leading ports in China.

Another concern is that the supply chain crisis is fuelling a retreat from globalisation. It was after all, the humble supply chain that embodied the ‘promise’ of globalisation with the integration of production across and within borders.

However, today’s crisis is a consequence of how integrated and efficient global production has become. Many companies adopted outsourcing, offshoring and just in time inventories.

The share of world trade accounted for by global value chains (in which products cross at least two borders) rose from around 35 percent in the 1970s to more than 50 percent today. This crisis has once again re-energised the debate for nearshoring or bringing production closer to home while also calling into question the value of just in time supply chains.

Companies and governments alike have woken up to the risks of dependence on distant suppliers and the reality that more points along supply chains mean more potential single points of failure that can be disrupted by natural disasters, infrastructure shutdowns or geopolitics.

According to the Boston Consulting Group, there are over 50 points in the global semiconductor supply chain, which means that each point could result in a breakdown.

So far, COVID-19 has posed the biggest threat to supply chains, shutting down production, closing borders and resulting in job losses. But this should presumably pass once restrictions are lifted and borders reopen as vaccination reduces the severity of the virus.

On the flip side, climate risks are likely to grow for two reasons: more frequent extreme weather events and the transition to renewable energy (which lacks the capacity buffers of fossil fuels, and cannot be stored like oil and gas – at least not yet). In contrast, solar and wind energy can disappear altogether if sun or wind are absent.

Finally, protectionism – which has been around since 2008 but reared its head yet again during the Trump era when Sino-US friction escalated – is still ever-present with the United States, China and Europe treading the path of self-sufficiency in important sectors, such as semiconductors and batteries.

The supply chain headaches that were viewed as temporary at the onset of the pandemic are now expected to last through next year. It is imperative that companies rethink and reinvent their supply chains if such crises are to be averted in the future.