SRI LANKANS OVERSEAS

A PARADISE DESTROYED?

Niranjan Navaratnarajah

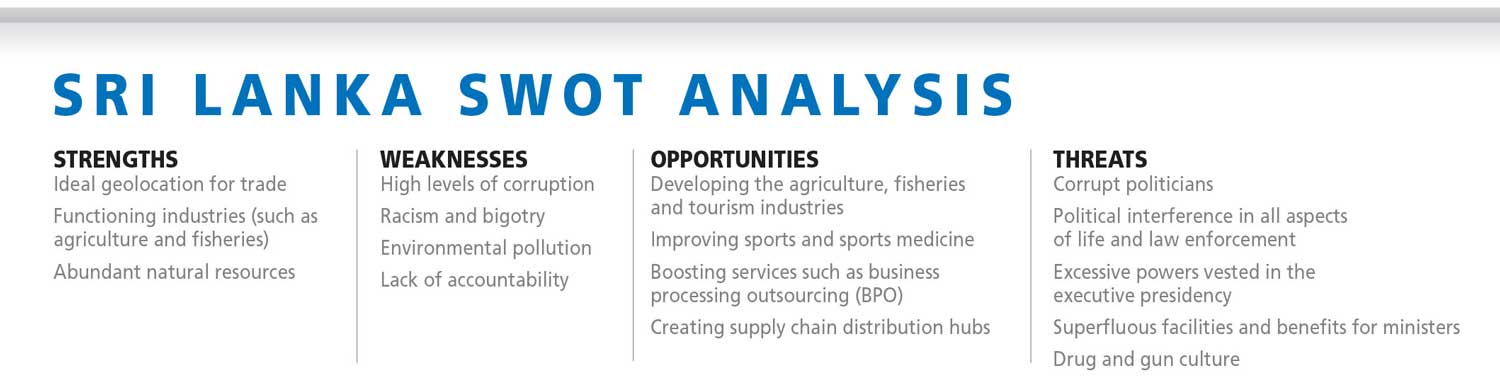

Why a paradise state has been lost despite its many strengths

Q: How do compatriots in Australia view Sri Lanka?

A: They consider it a paradise state with educated and hospitable people – but one that has been destroyed. People ask why justice isn’t meted out to those responsible. Revelations about money laundering and street demonstrations heightened their knowledge of organised plunder.

Now most are willing to help – but not under the current structure. They would like to see an accountable and responsible regime in place to attract foreign direct investments (FDIs) for development.

Q: Likewise, how do other Sri Lankans living where you do perceive their homeland?

A: They feel it has been robbed of its future by the previous regime in terms of money, land and reputation. There is a culture of intimidation, fear mongering, murder, obstruction of justice and concealment of evidence.

People are also concerned that the sale of national assets will blight the future of its youth.

Q: What were your impressions of Sri Lanka on your last visit – and how much has it changed from the past?

Q: What were your impressions of Sri Lanka on your last visit – and how much has it changed from the past?

A: There’s been a significant change. Absolute gems such as Ella, which is a world-class location, need to be carefully managed and regulated. The highways are impressive but the hotels are basic and costly, and service is below par.

The economic crisis has left people with scars and they are fed up with politicians. Youth and professionals are migrating, and this has resulted in a major brain drain.

Due to excessive logging in rainforests, temperatures across the island have increased. However, Sri Lanka still has great potential for growth.

Q: So in a nutshell, your take of Sri Lanka is…?

A: It is a failed state, sadly; and there’s no hope with current governance mechanisms. Corruption and nepotism are fully ingrained into society, and race and religion are used to promote inequality and hold on to power.

Unlimited borrowing for white elephant projects has resulted in a debt trap. Despite the aragalaya seeking regime and system change, the culprits are still clinging on to power and have no idea how to build a sustainable future.

Q: And how do you view life in the country of your residence? What do you appreciate most about Australia?

Q: And how do you view life in the country of your residence? What do you appreciate most about Australia?

A: Australia was built with a long-term vision and the government is only a temporary custodian. There is freedom of expression and that of the press. Stealing, bribery and corruption are punishable offences.

Australians are free to do what they want, wages are high, people are educated, power is devolved to the states, there’s religious freedom, and a culture of ‘live and let live.’

Q: Do you think Sri Lanka is capable of regaining its composure in the aftermath of multiple crises – including the most recent economic crisis?

A: It will be difficult under the current political culture and structure. That’s why regime and system change are essential. There needs to be a transformation in the political culture of the country whereby politicians are held accountable by the people.

The country will prosper only when people vote for change. There is scant hope in the existing governance process and the only option is for the establishment of a new party or coalition that will be able to govern with integrity.

Q: What should Sri Lanka focus on most in the coming decade?

A: It should focus on ensuring the fundamental rights of all citizens, and promoting homegrown industries, agriculture, the knowledge economy and tourism. It should also use its strategic geolocation to increase maritime and air traffic.

People need to be educated on ethical service delivery; jobs should have dignity; more universities should be established for the youth; a knowledgeable and thinking workforce must be developed; and soft skills and HR, as well as teaching and caregiving services, should be strengthened.

Q: And what are your hopes for Sri Lanka in the next decade or so?

A: By that time, Sri Lanka’s government would have punished those who have stolen national assets and money, and also recovered what has been taken away. Over the next decade, the economy should have stabilised and there would be no need for austerity.

The judiciary, central bank, police department, human rights commission and media would be independent of state interference. Last but not least, the executive presidency would have been abolished.

Leave a comment